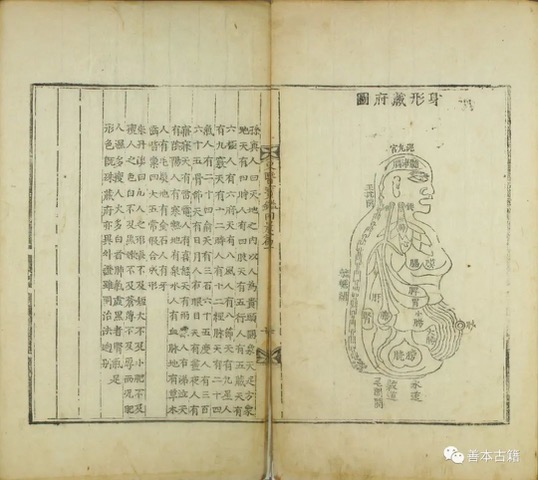

In the early Chosǒn period, Koreans drew from Chinese Daoist texts to visualize the body. Korean physicians also referred to images in widely-used Chinese medical texts such as Gong Tingxian’s Wanbing Huichun 萬病回春. However, in 1613, Hǒ Chun published the Treasured Mirror of Eastern Medicine, the first text claiming Korean originality in visualizing the body with a small number of images characterized by sparse minimalism. At variance with counterparts in China and Japan, Koreans in the Chosǒn period argued that to illustrate the inner body was to miss the point. They moved to more emphasis on the void or the emptiness of the body, by doubling down on Daoist-Buddhist ideas, such that Koreans did not publish any new visual interpretations of the body until the twentieth century. Even if Koreans understood the body as a metaphor for the state, they did not illustrate it. they found written text adequate to explain the inner body as both a site of bodily functions such as digestion, related to production of ki and blood. as well as a haven for a host of divinities or spirits. The small intestine, Hyǒnnyǒnggong 玄靈宮(profound and divine palace), is piled up like leaves from the left of the umbilicus. Fermented food and water in the stomach are transported to the small intestine. Clearness and turbidity are separated at the exit of the small intestine. Waste then enters the large intestine, the Minyǒnggong 未靈宮(Last Divine Palace). It winds to the right, piled up in 16 layers. Koreans shared with their Chinese and Japanese counterparts the conceptualization of the key role of the spleen in digestion, coordinating the storing, processing, and excreting roles of the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Furthermore, the spleen was in charge of the flesh of the body. Less interested in appearance and physical function, Koreans showed more interest in the spleen and stomach as the center of the body, not only in terms of location but crucially in terms of its role as the center of thought or ideation, the Yellow Court. In this way, Koreans placed more emphasis on the idea of the connection between digestion and thinking than on visual appearance. This understanding of the role of the guts as central to clear and lucid thought, as well as the production of ki, continued well into the twentieth century. Linked with Daoist divinities, the guts acted as a metaphor for the human links with the world of spirits and higher ideation.