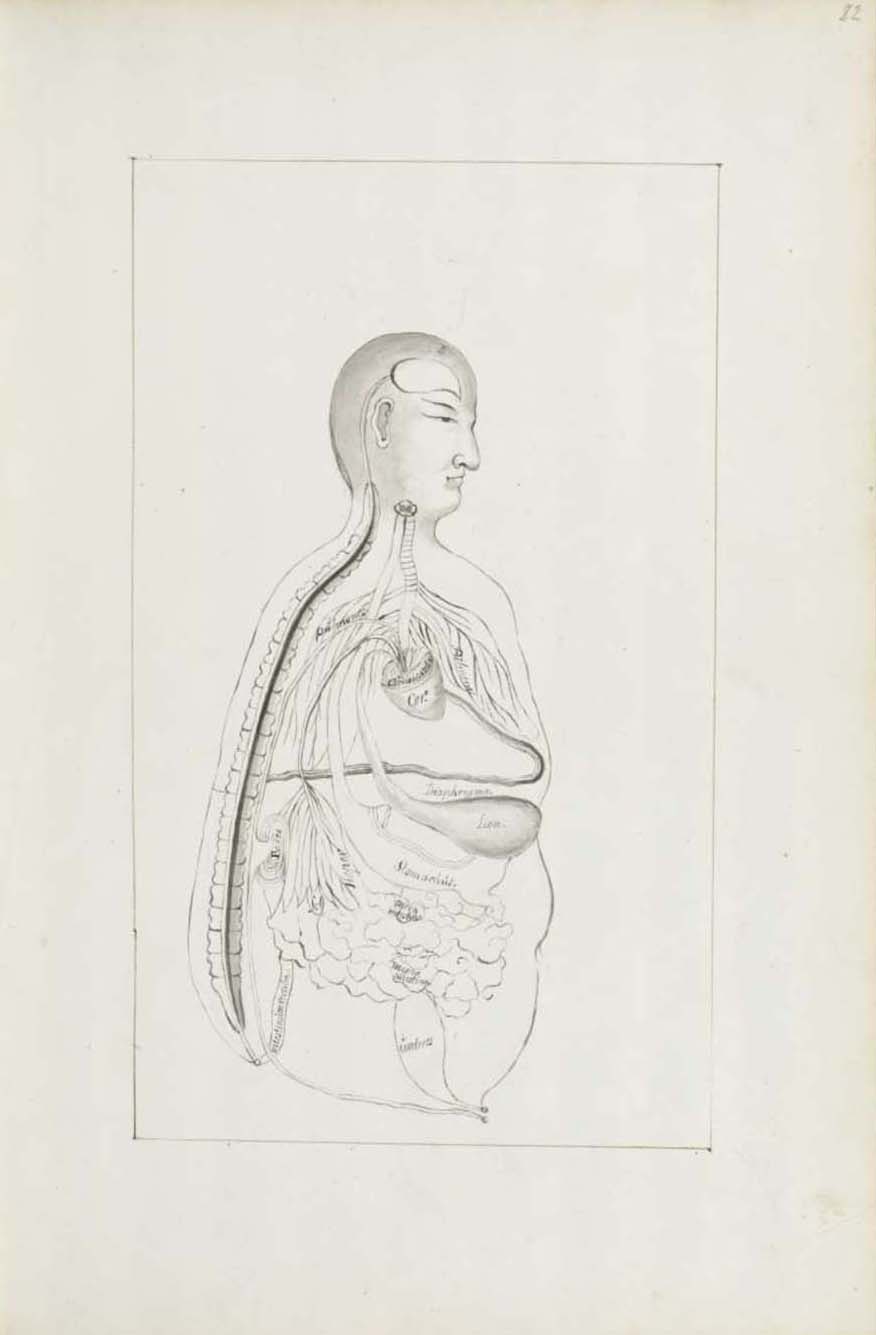

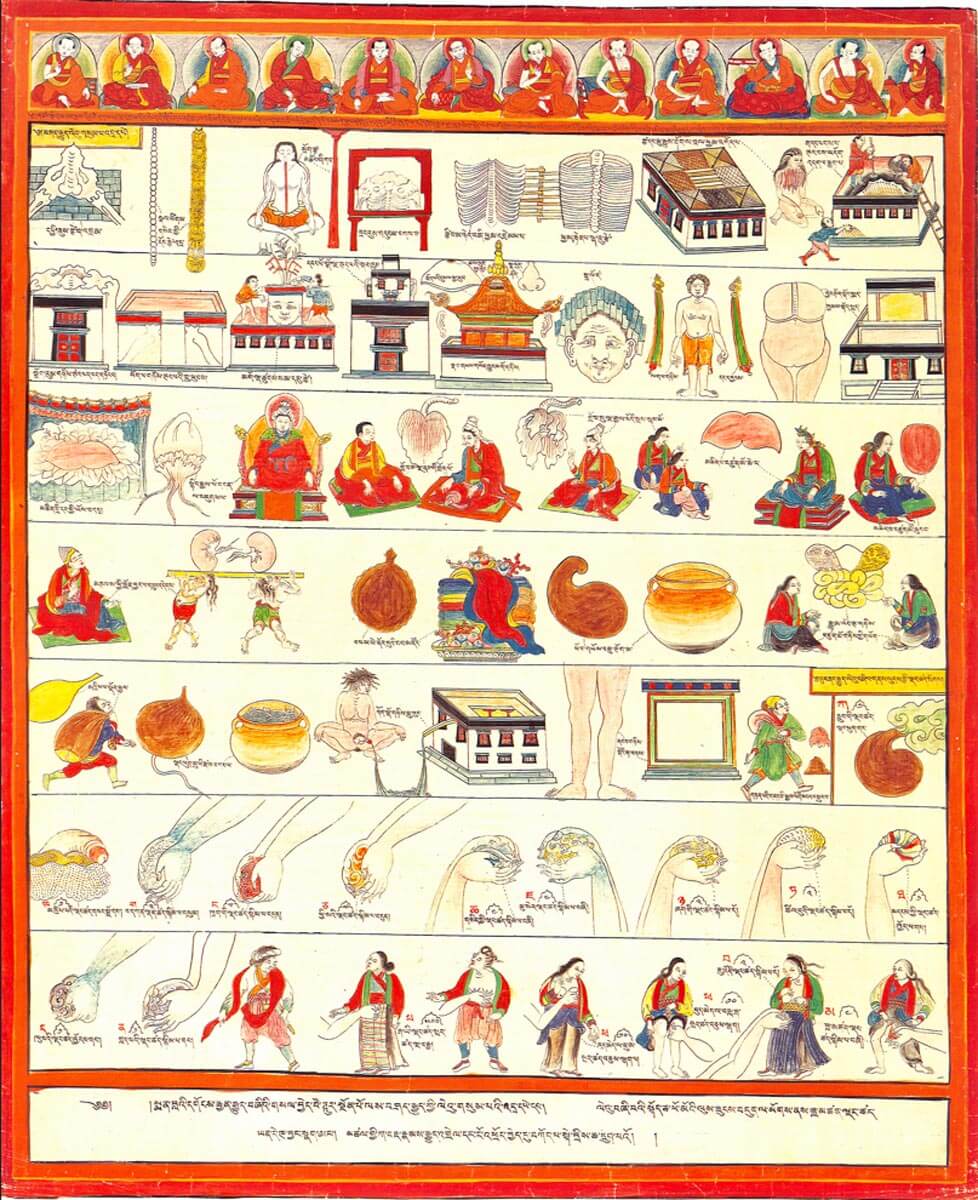

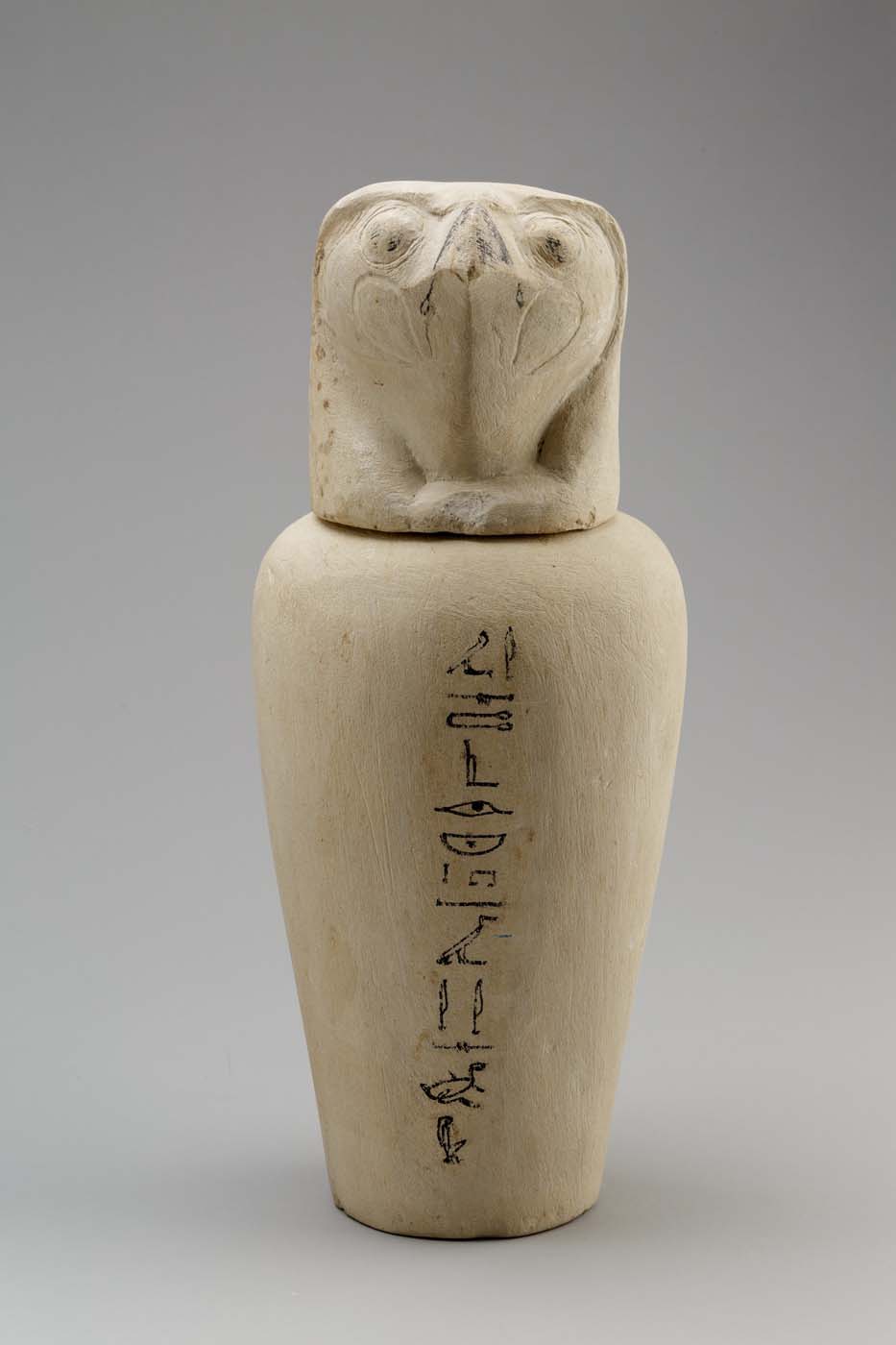

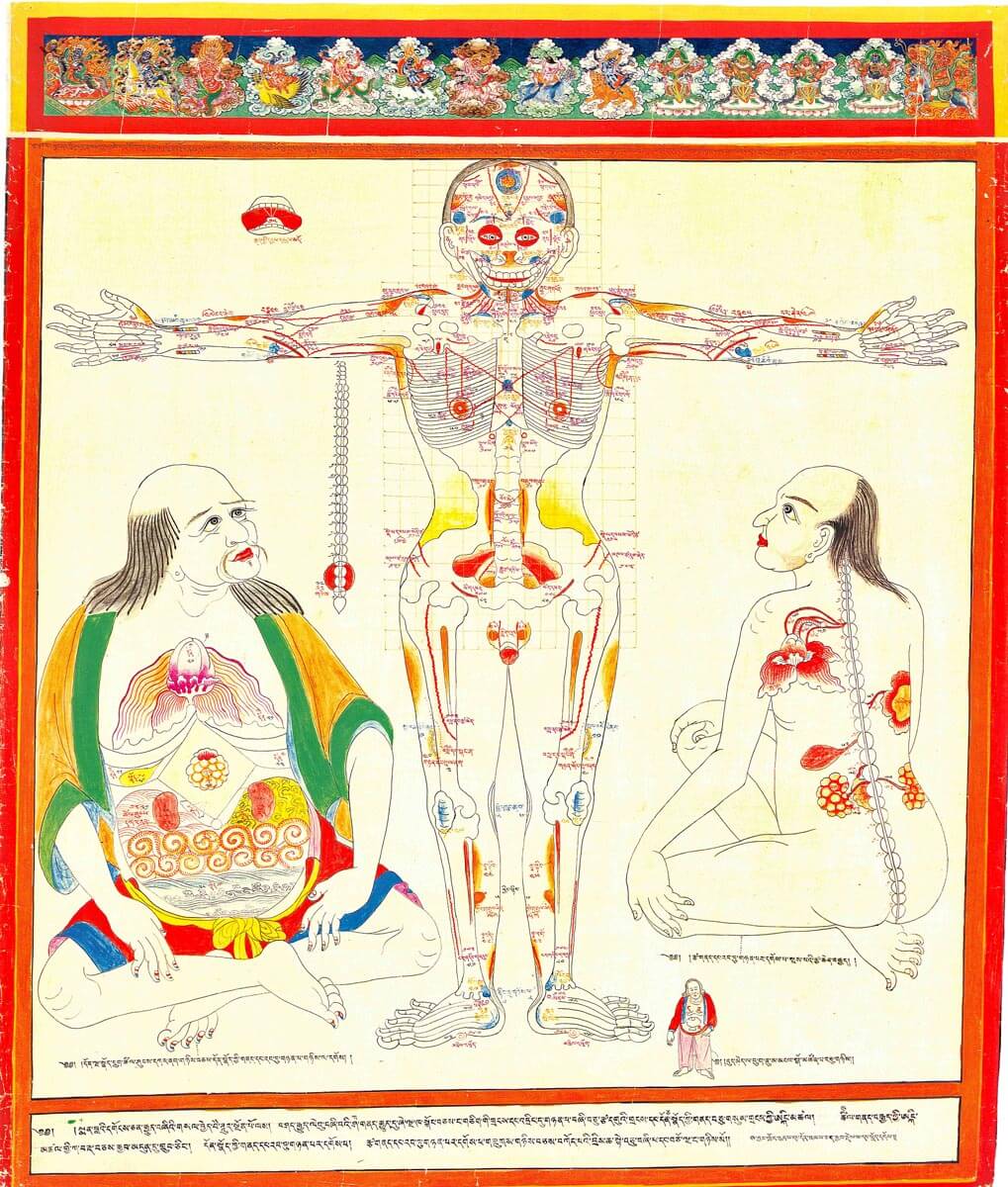

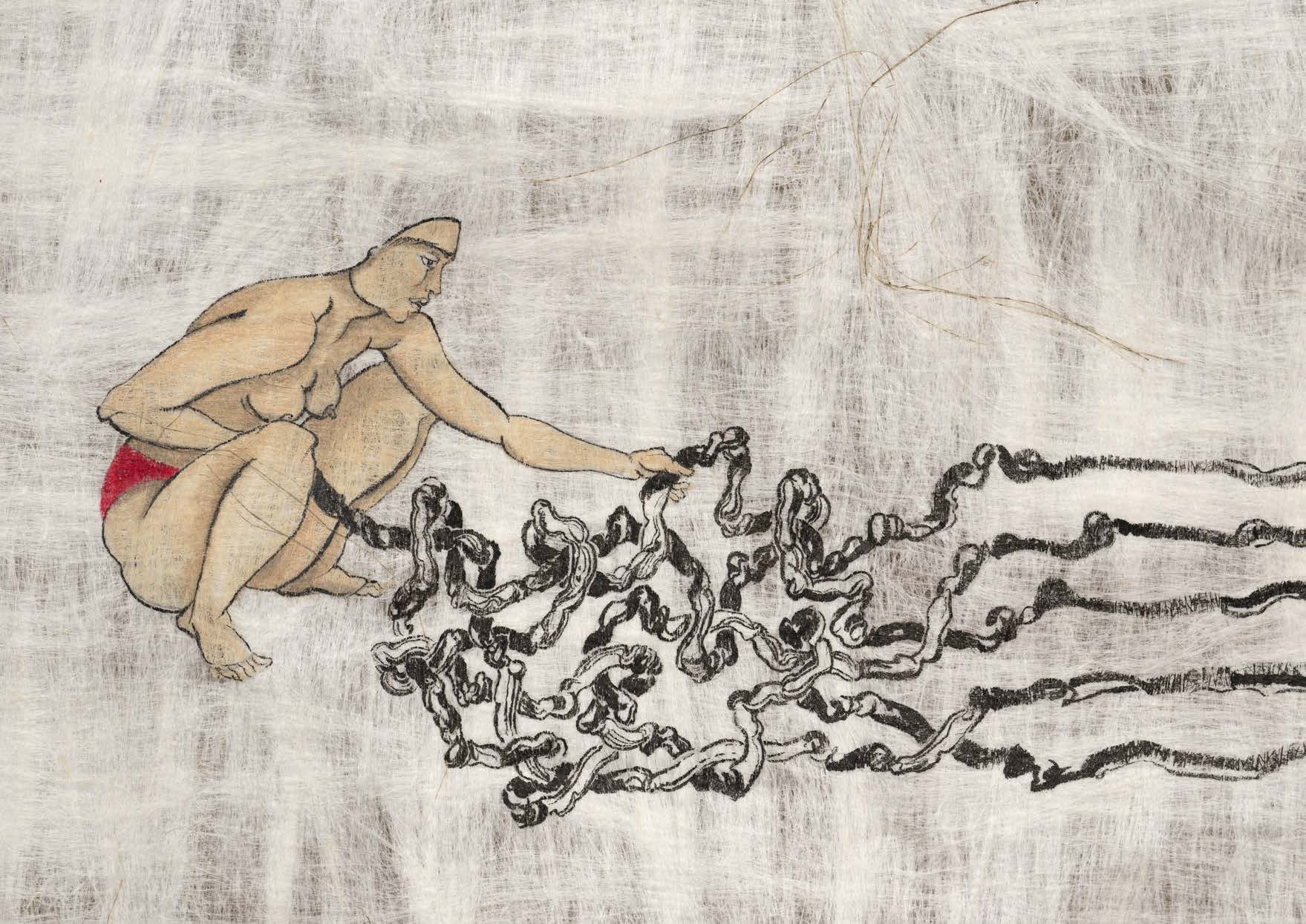

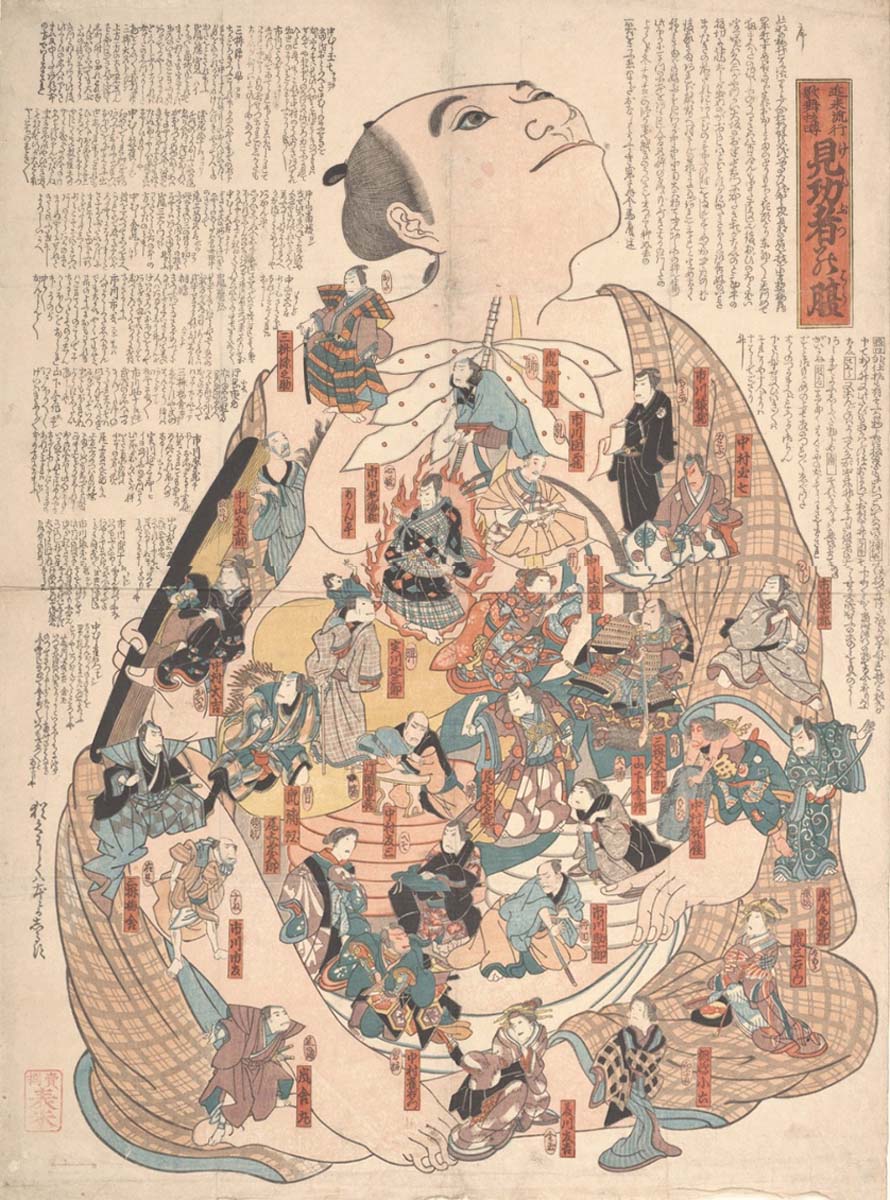

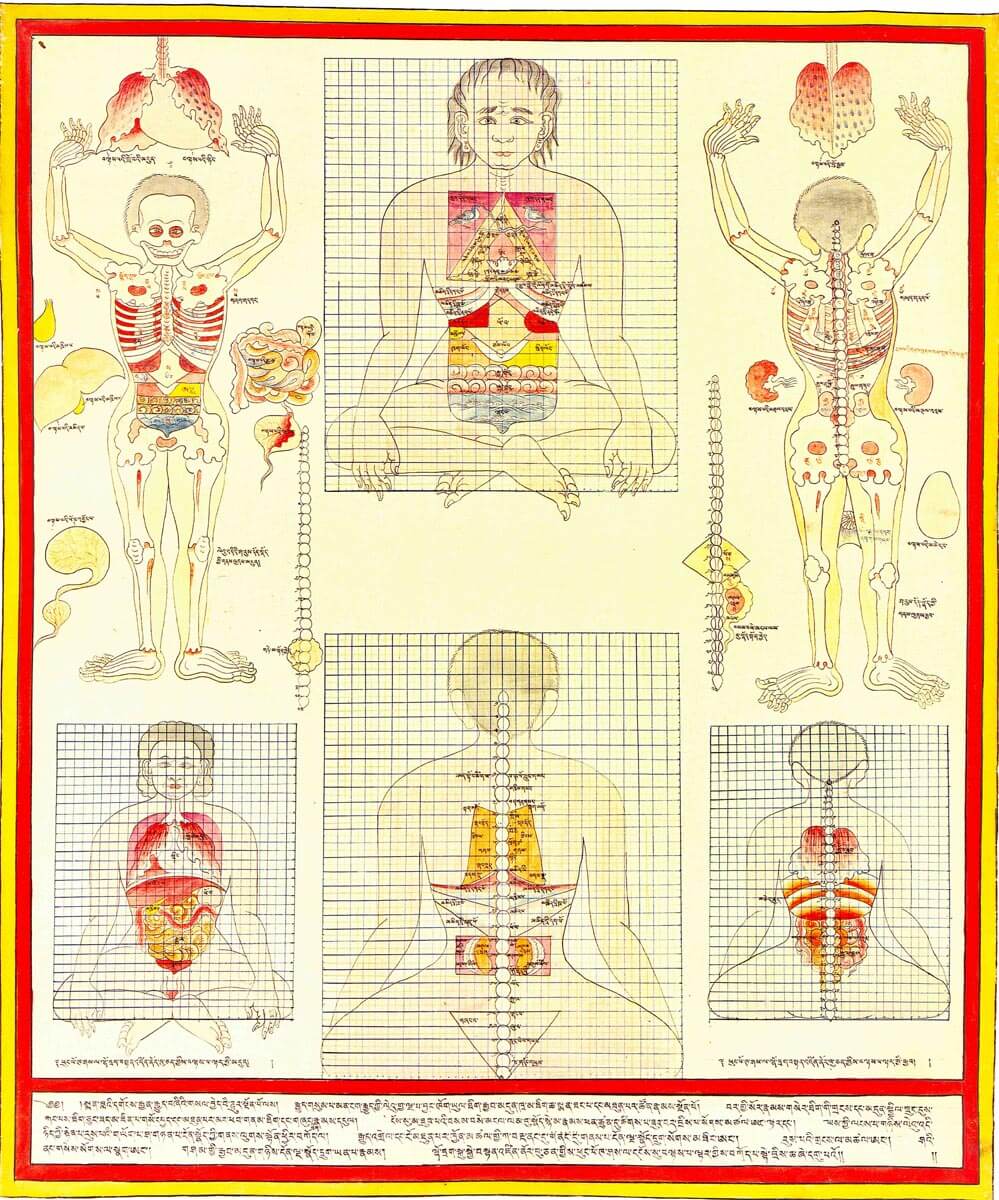

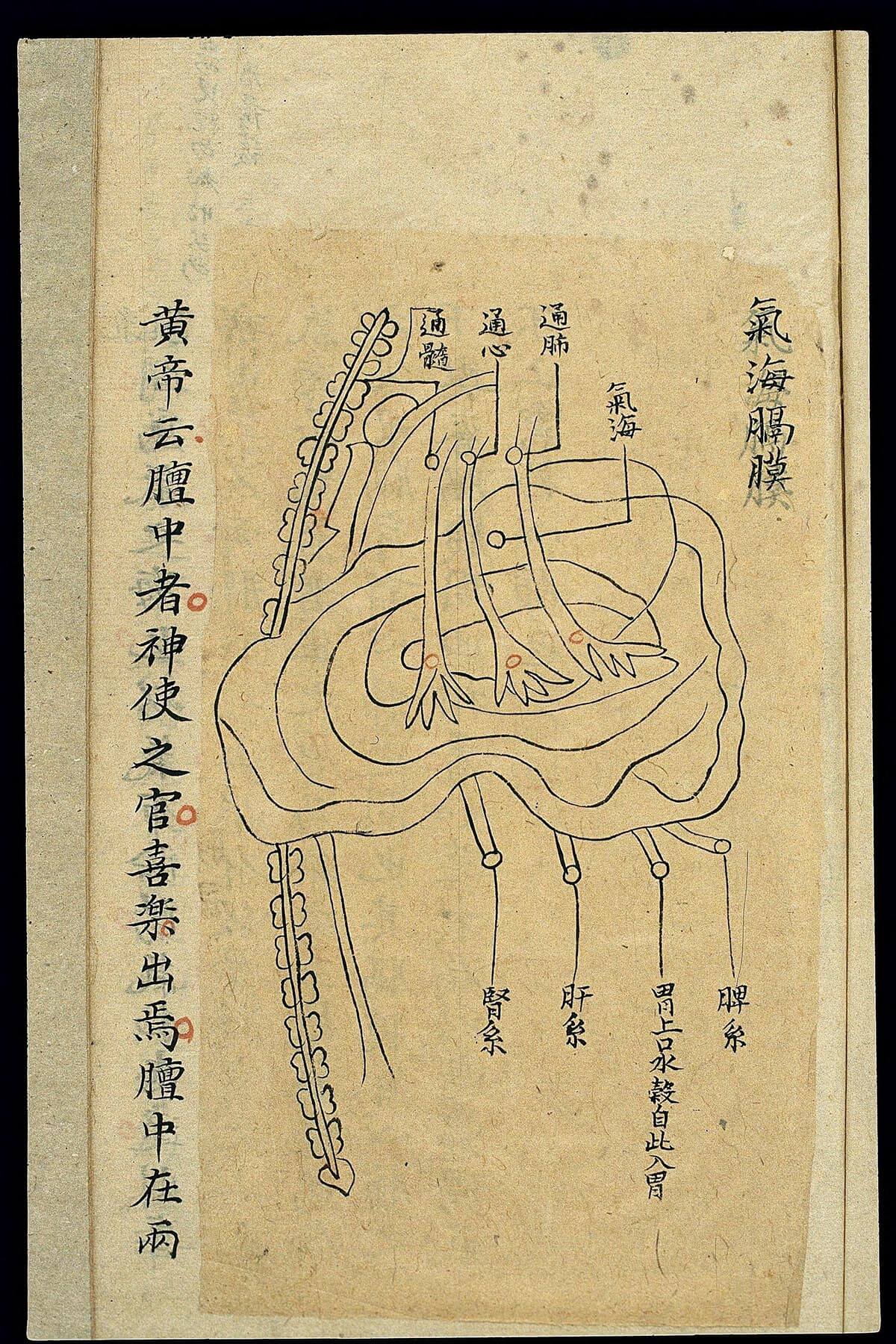

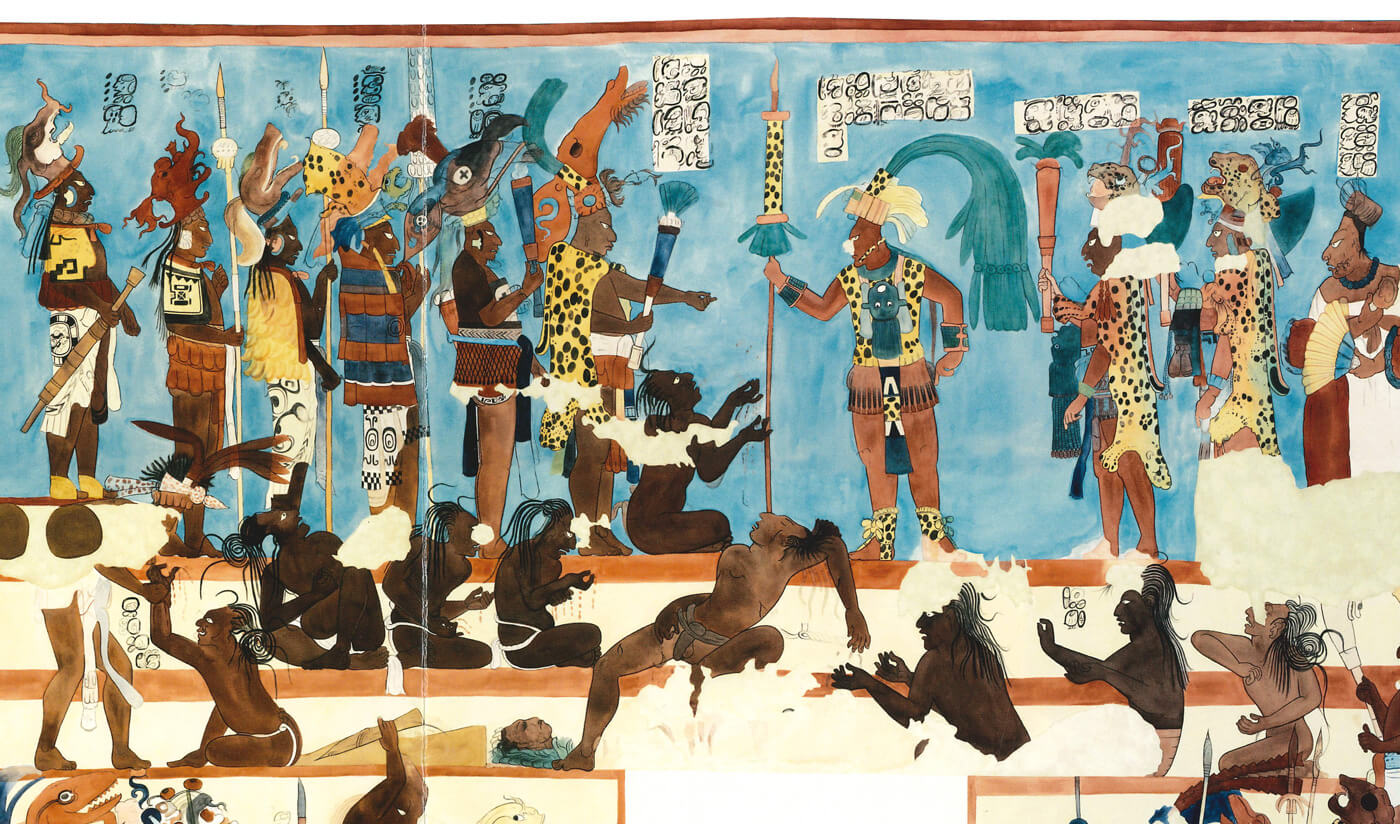

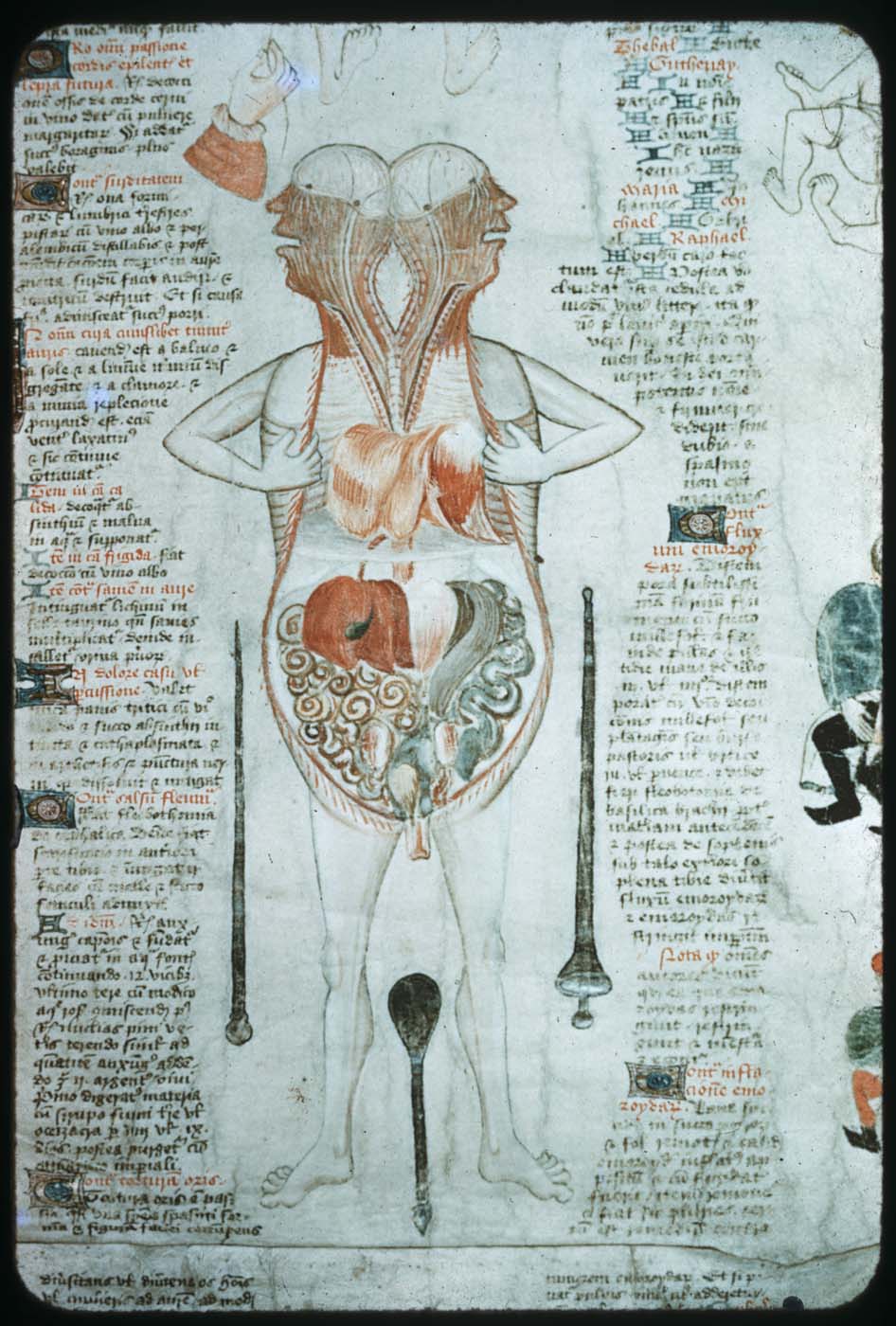

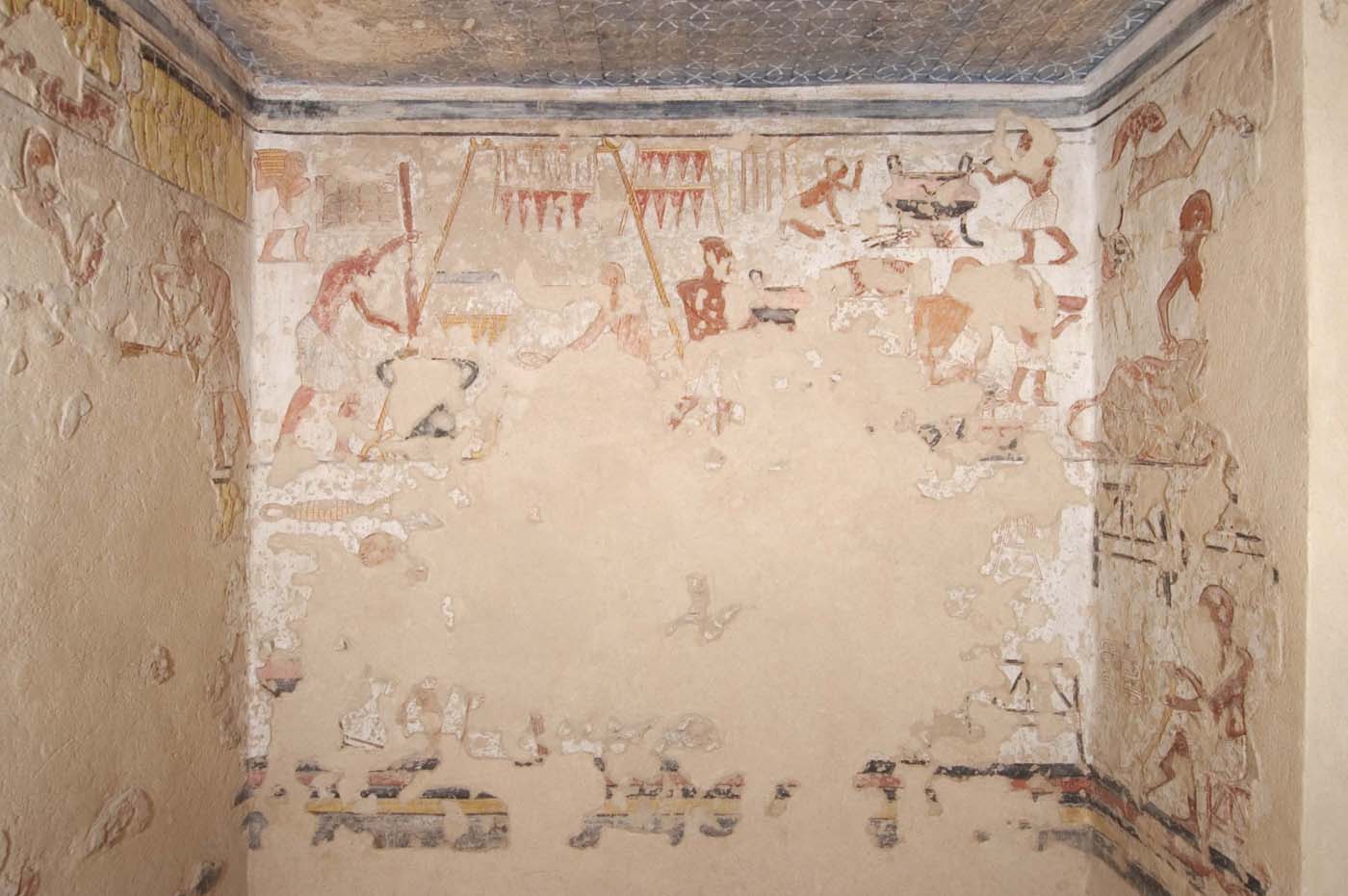

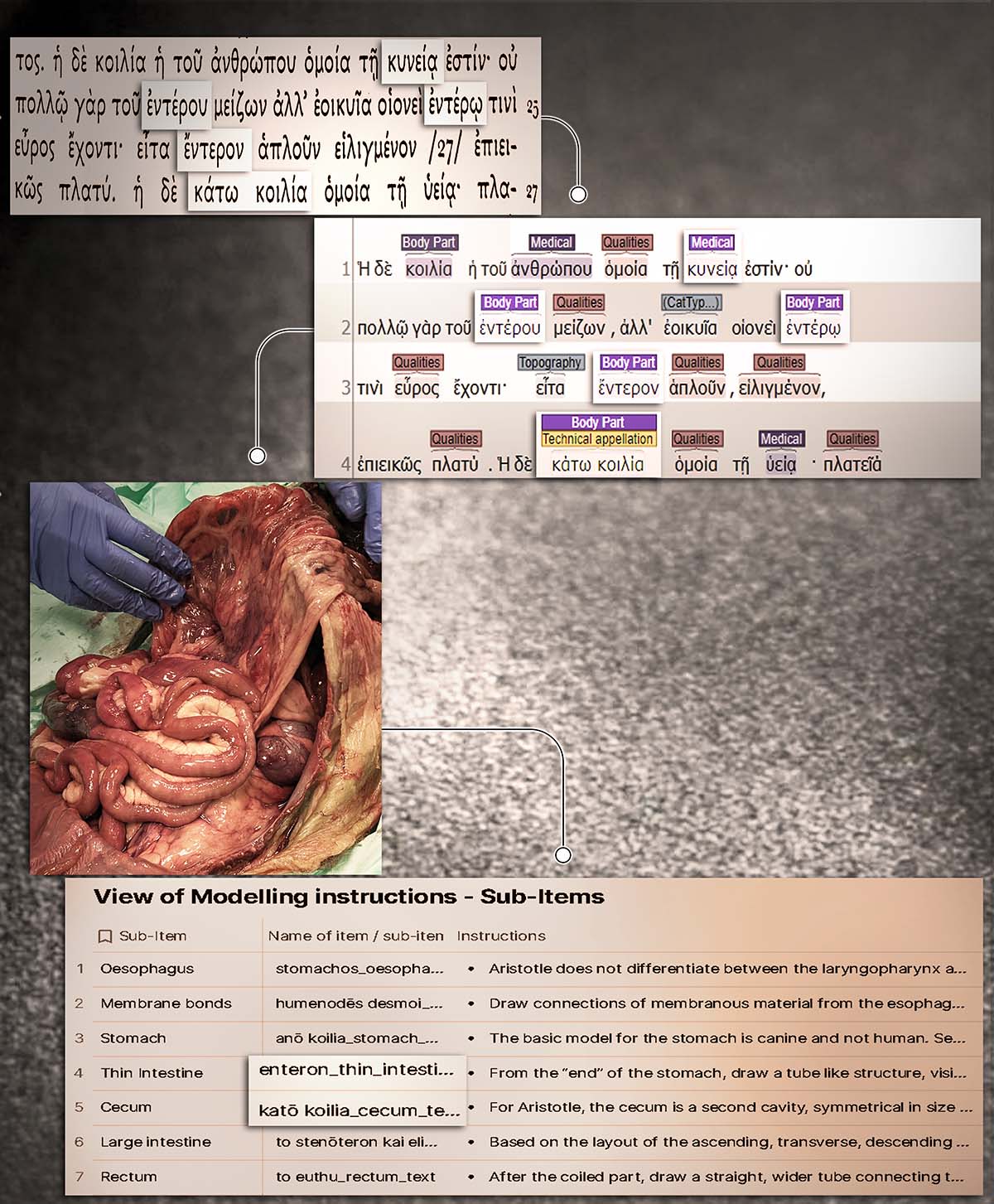

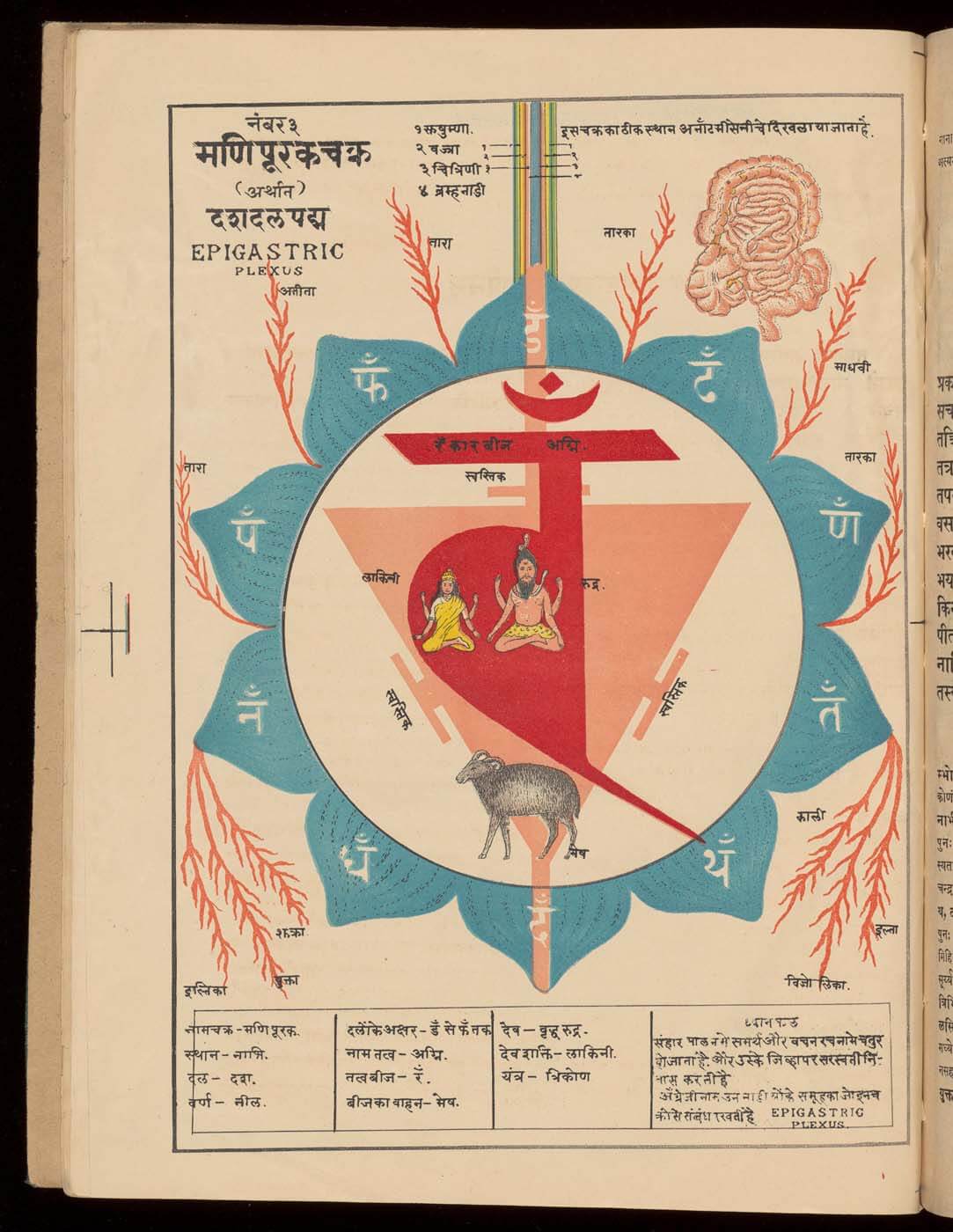

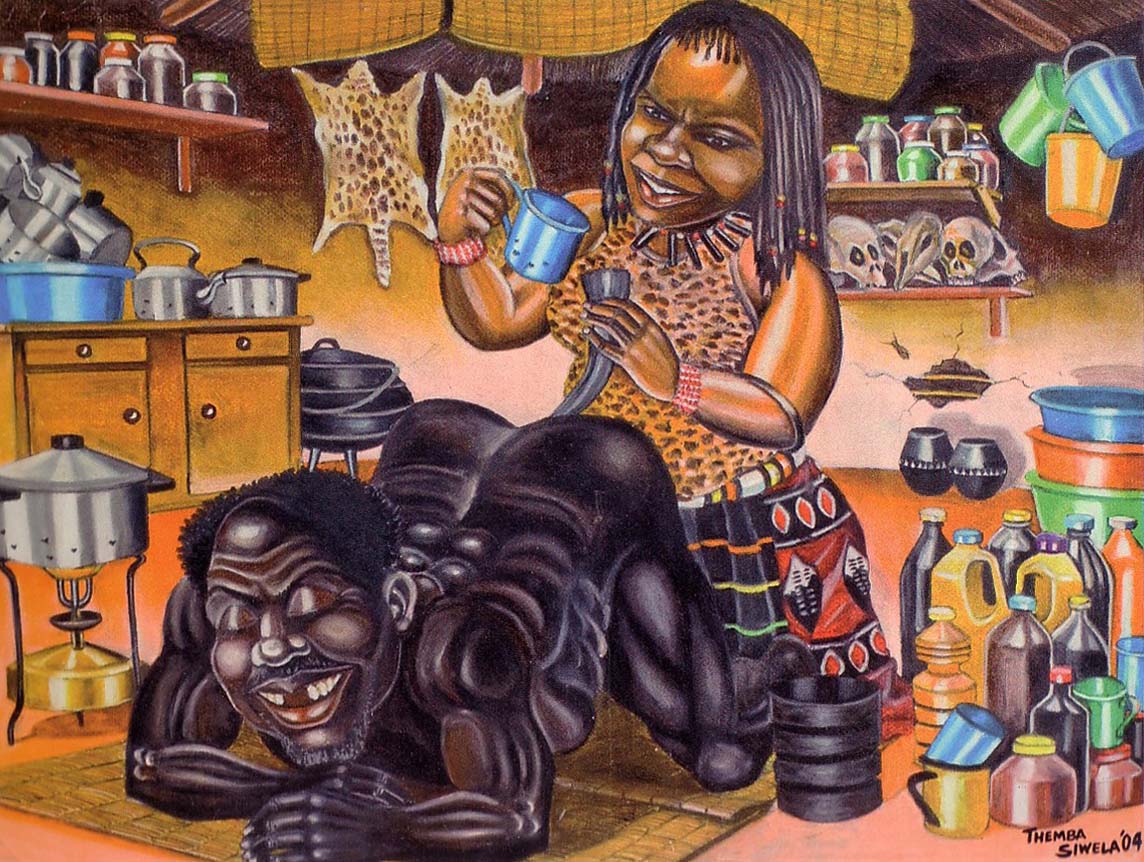

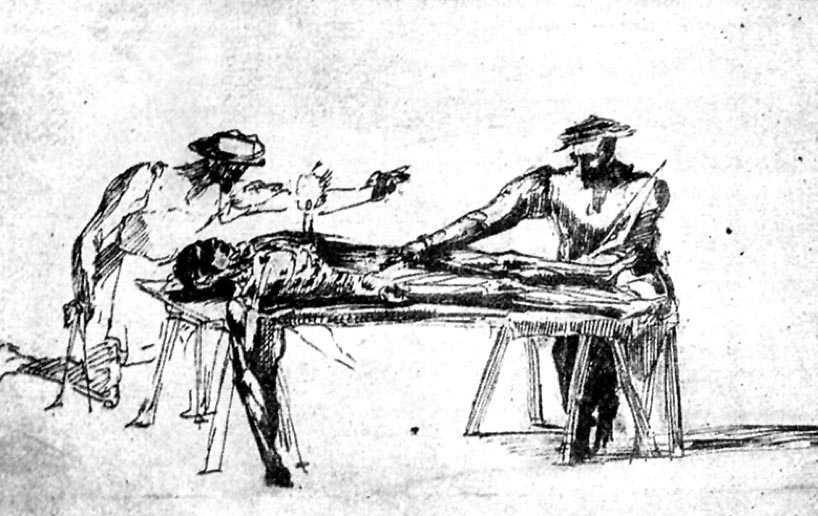

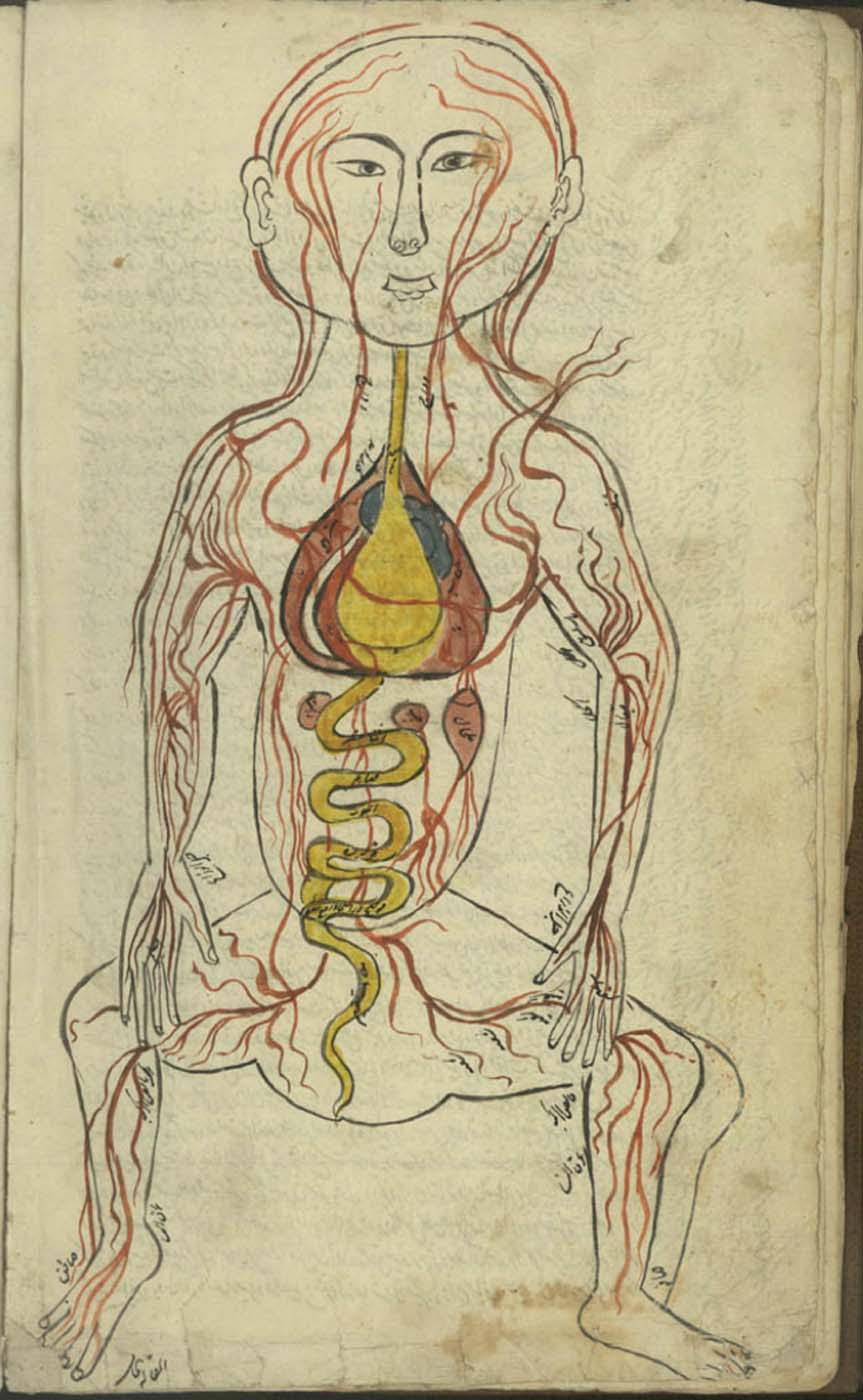

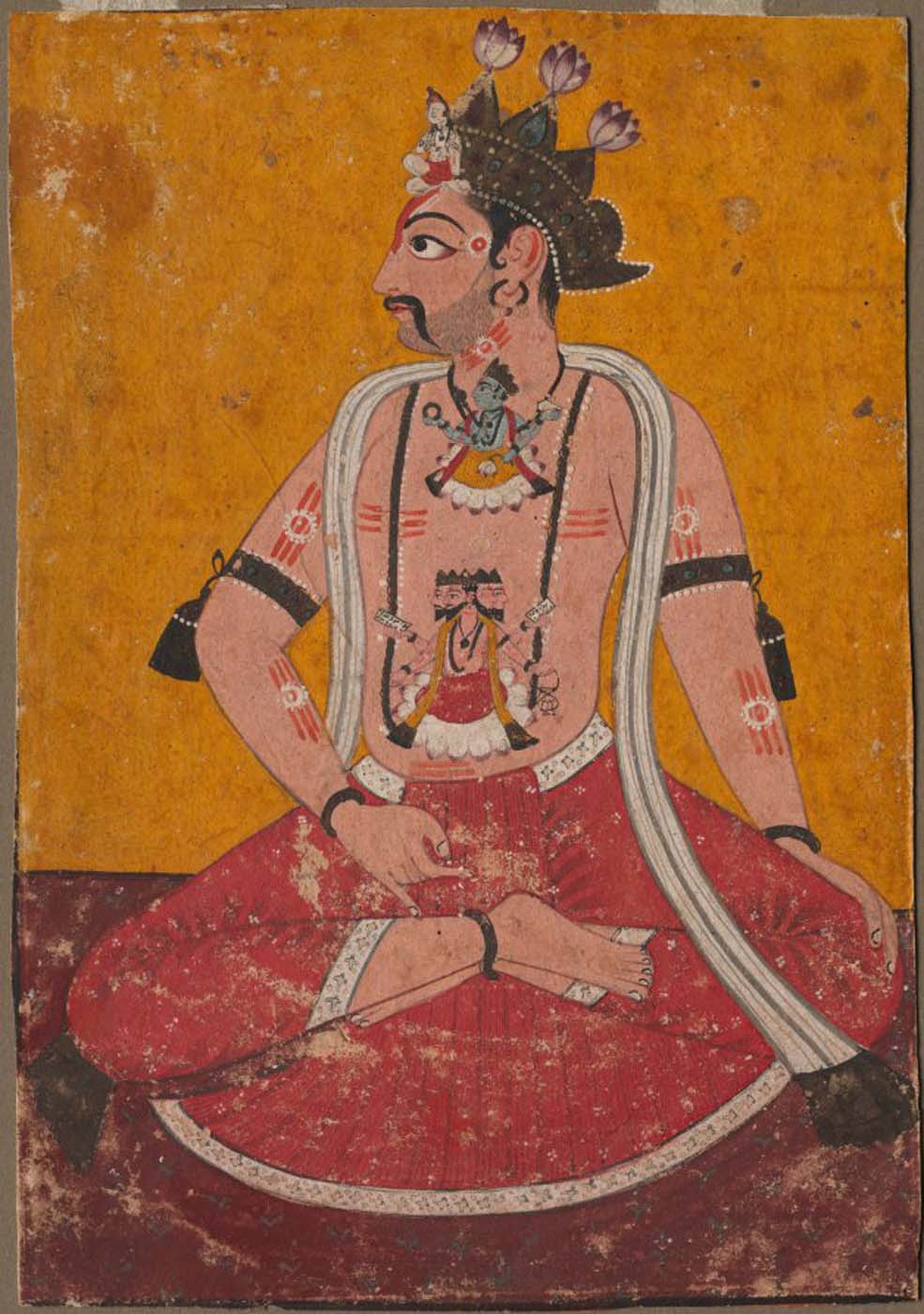

This is a comparative exhibition about the human body, and in particular about one body part, the ‘guts’. For these purposes, ‘guts’ refers to everything found inside the lower torso, the organs and parts traditionally linked to nutrition and digestion, but also endowed with emotional, ethical, and metaphysical significance, depending on the representation and narrative.

By offering access to culturally, socially, historically, and sensorially different experiential contexts, Comparative Guts allows the visitor a glimpse into the variety and richness of embodied self-definition, human imagination about our (as well as animal) bodies’ physiology and functioning, our embodied exchange with the external world, and the religious significance of the way we are ‘made’ as living creatures. This dive into difference is simultaneously an enlightening illustration of what is common and shared among living beings.

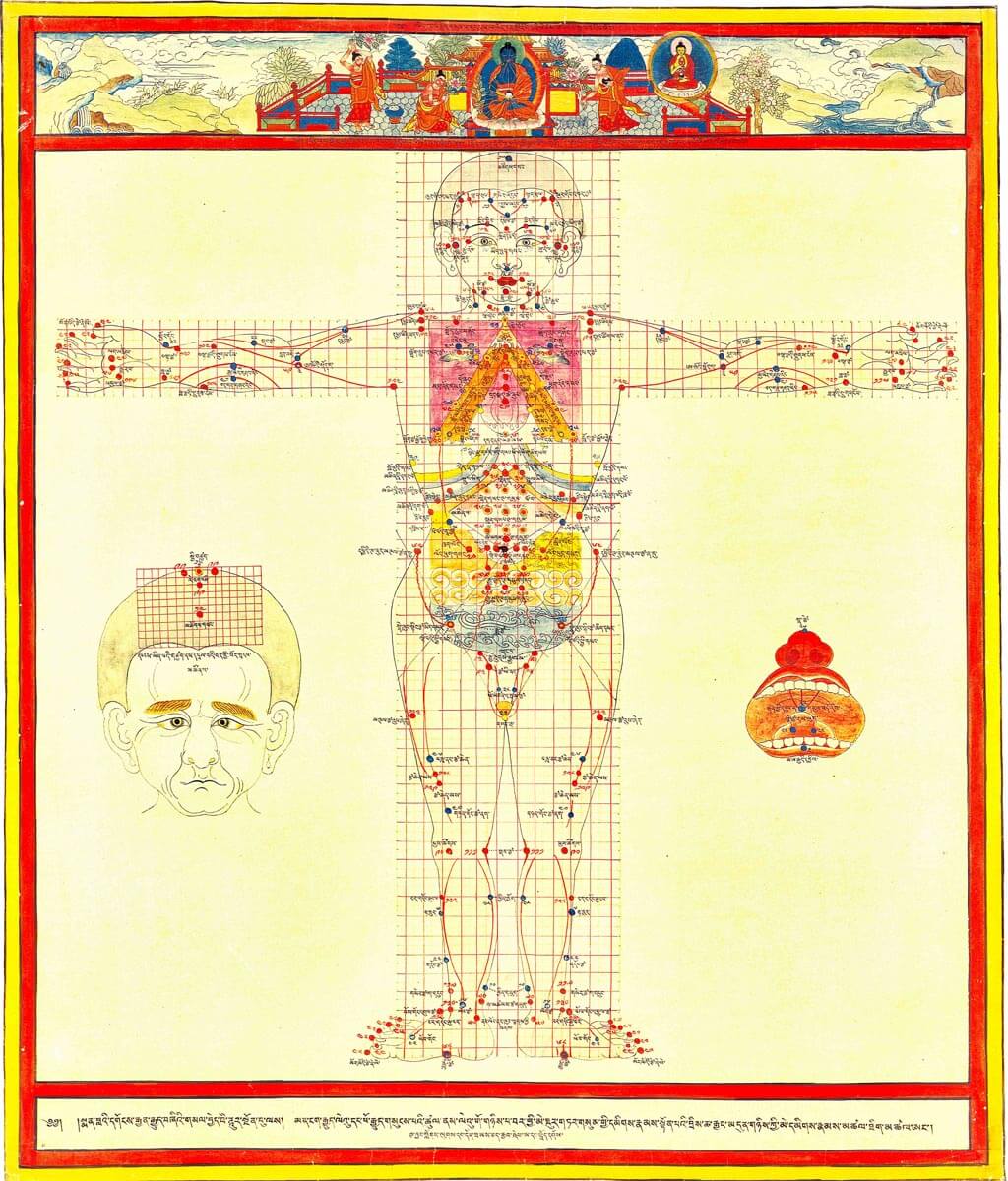

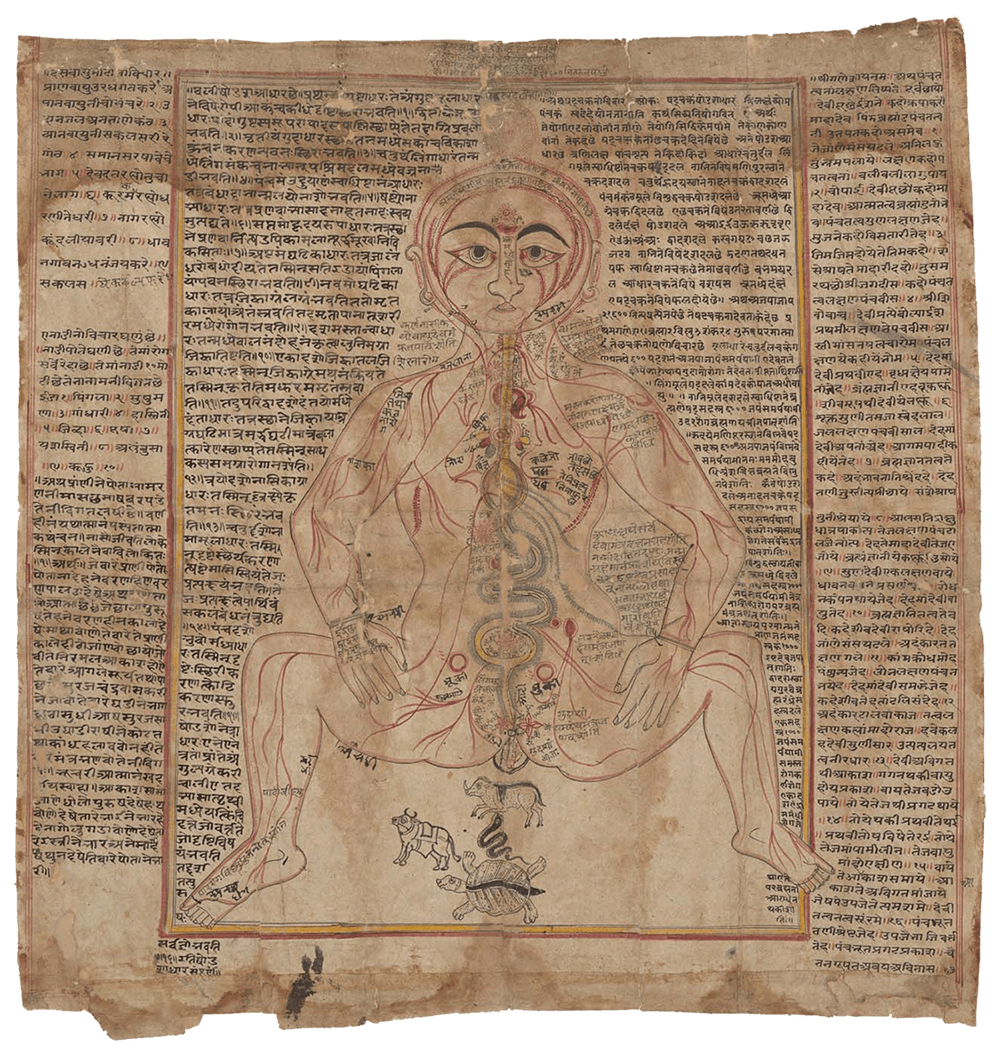

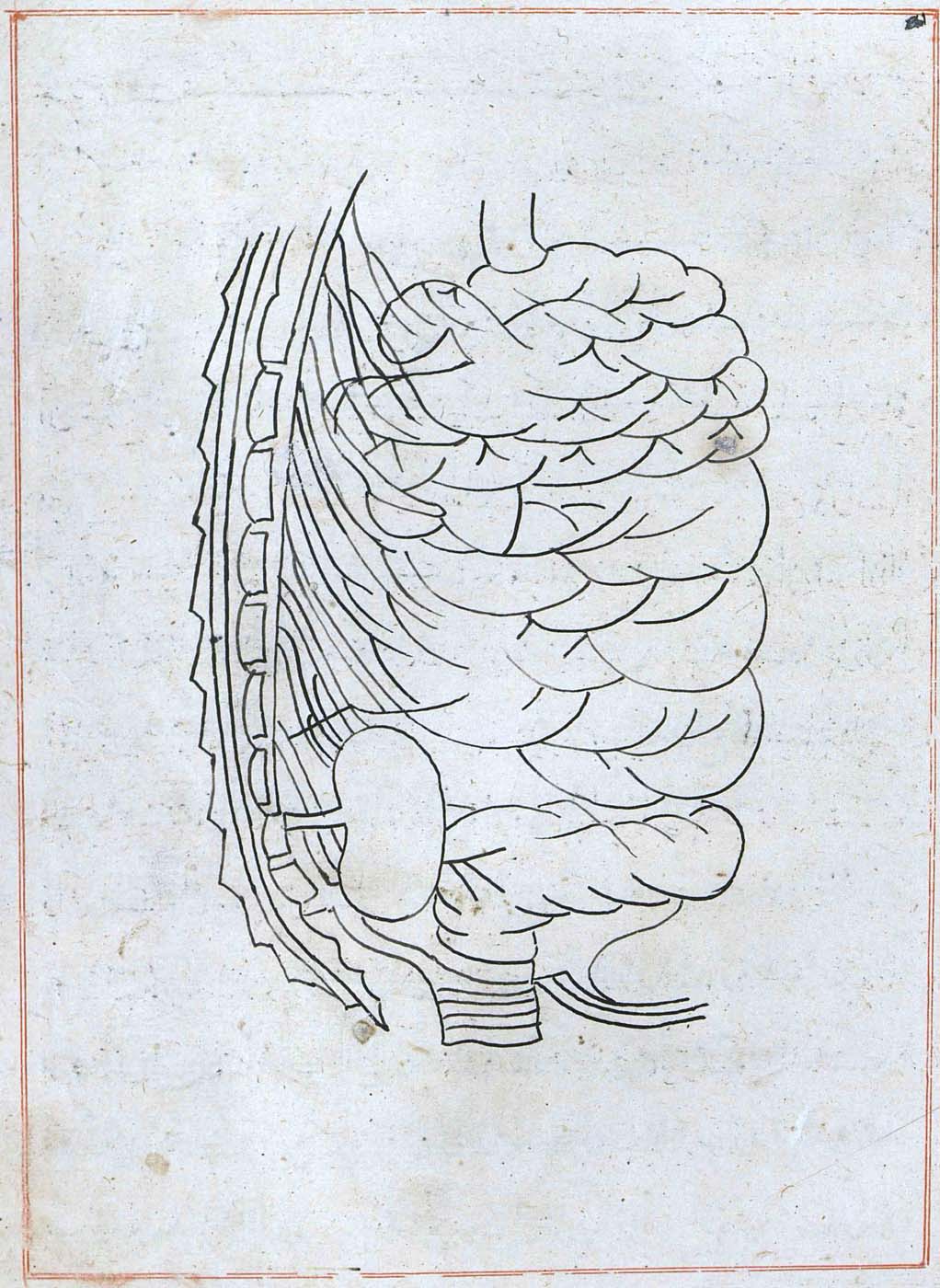

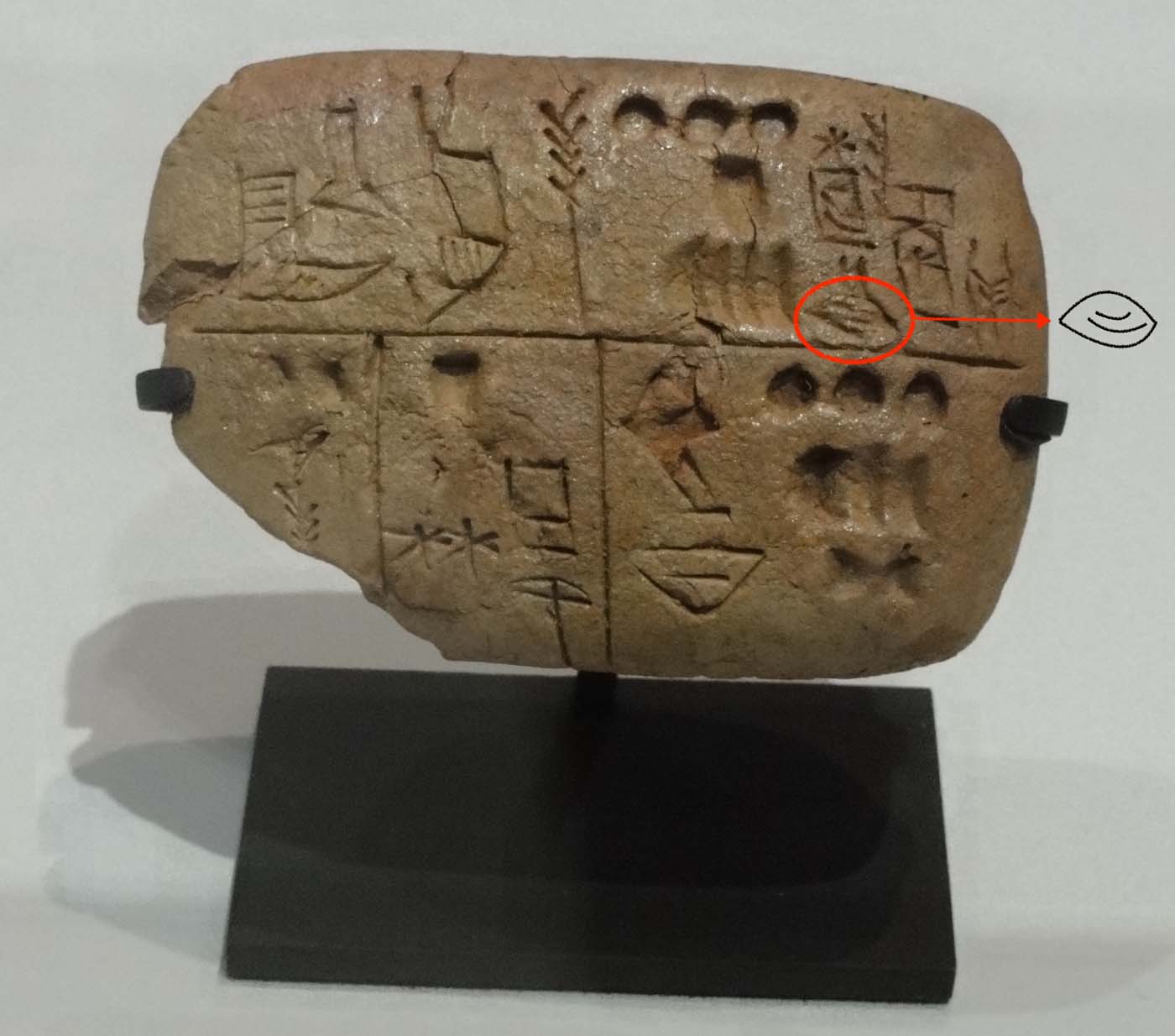

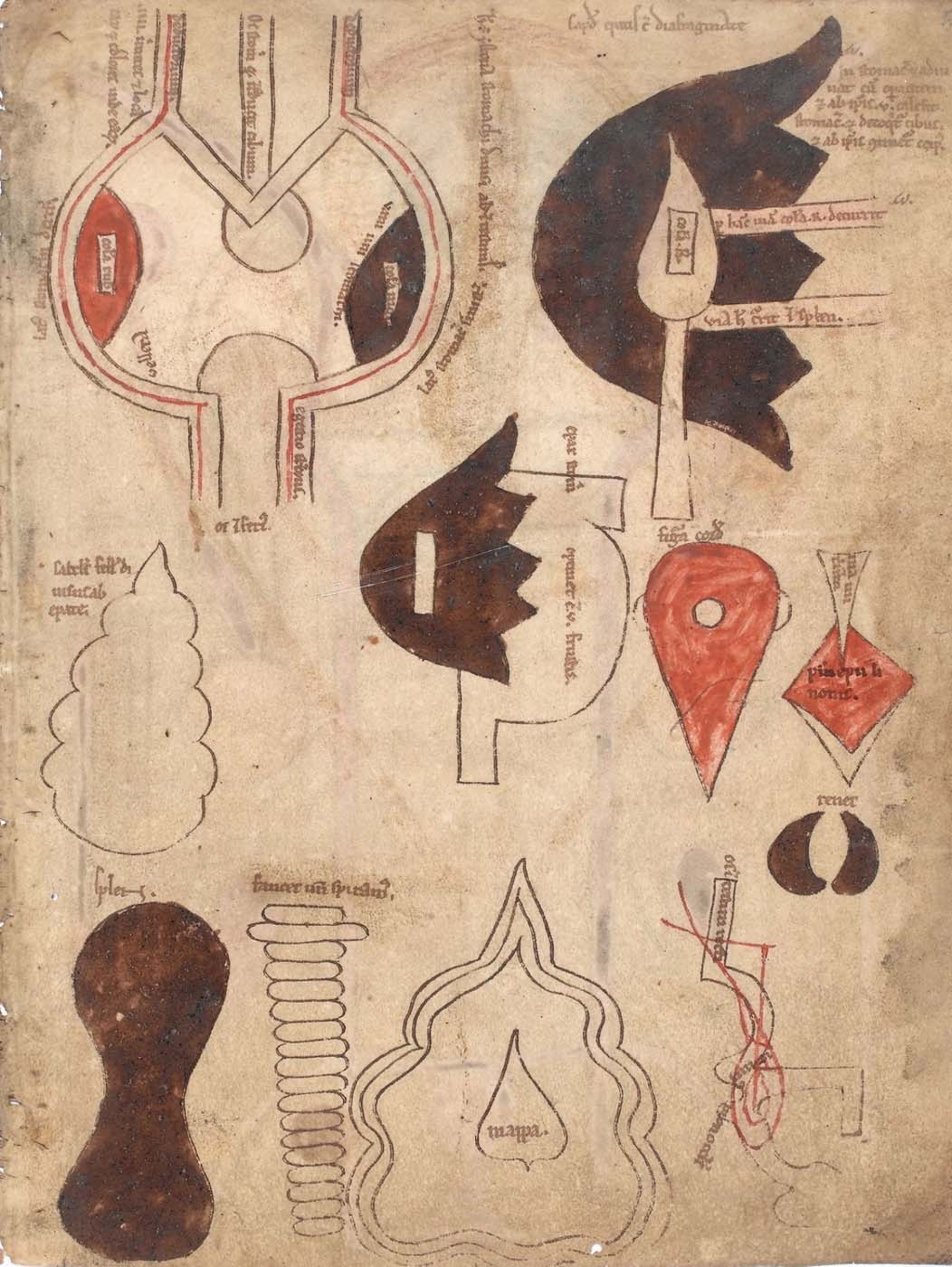

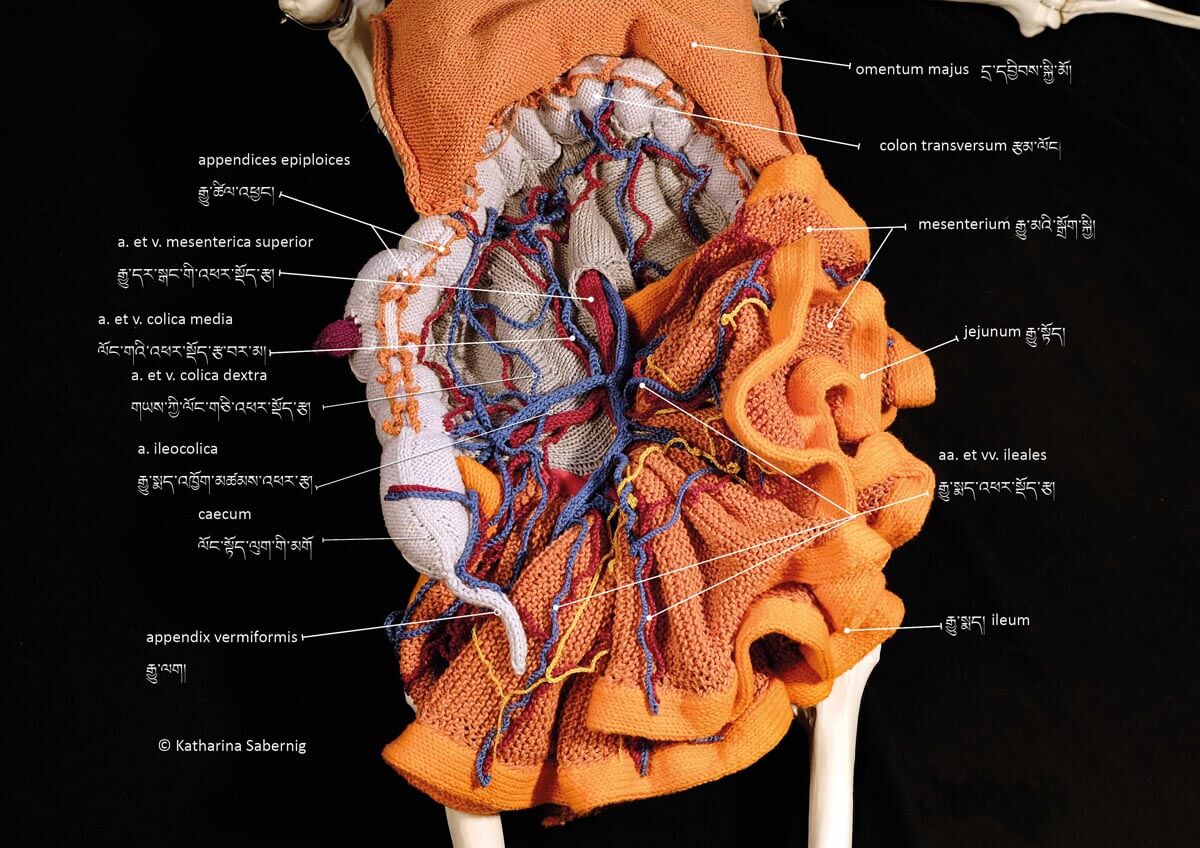

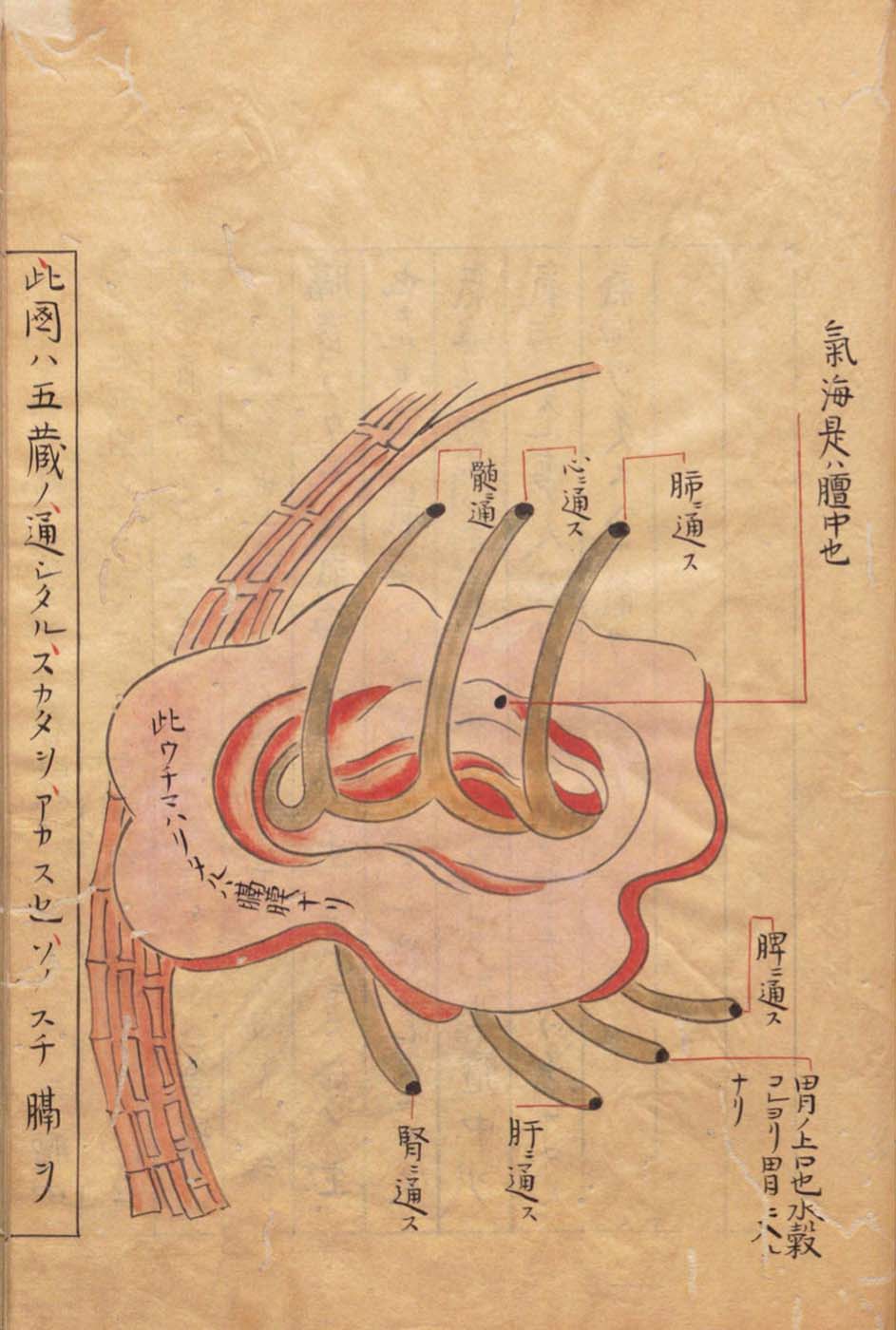

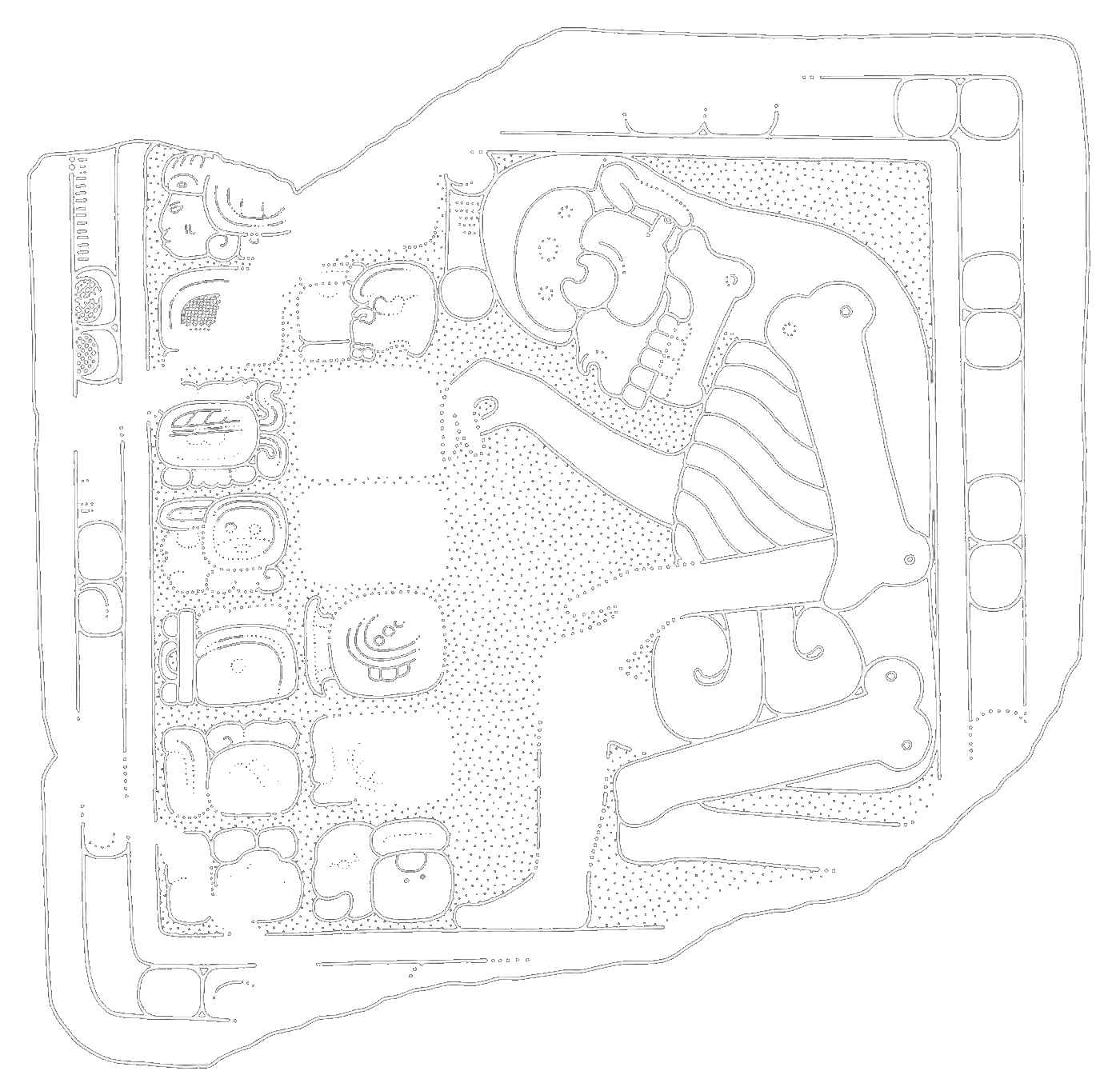

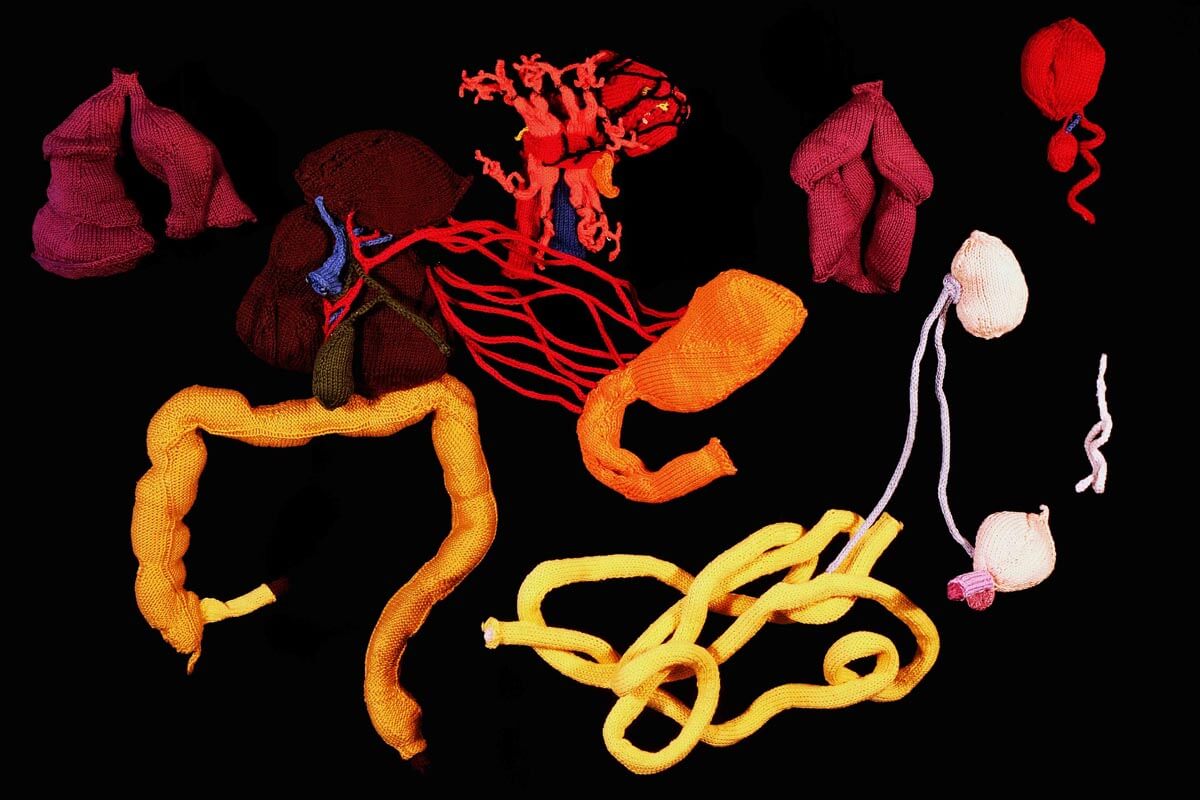

The ‘guts’ are treated here in as neutral and universal a fashion as possible: not necessarily as functional parts of an organism or as a medical item, but as realities experienced in various ways. The most basic distinction is the sensed, volumetric one: solids for the fleshy organs (such as those referred to in English as the liver and the stomach), coils for the intestines and other parts endowed with complexity, folds, and fluidity, and wholes for the guts understood as part of a coherent whole, be it continuous or assembled.

- All

- Whole

- Solid

- Coil

![SET 2a+b Huangting dunjia yuanshen jing (Buch der verborgenen Periode und der kausale [Karma] Körper des gelben Hofes) Die beiden Schwarz-Weiß-Bilder aus dem 15. Jahrhundert zeigen unter einem Text in chinesischen Schriftzeichen vogelähnliche Wesen. Auf dem mit „A“ gekennzeichneten hochformatigen Bild links nimmt die Darstellung des Wesens die unteren zwei Drittel ein. Das Wesen ist schreitend mit angelegten Flügeln im Profil dargestellt. Es hat lange, dünne und unbefiederte Füße mit Krallen. Die Unterseite des schlanken kleinen Körpers ist hell. Das Deckgefieder ist gebändert. Lange Schwanzfedern, die in ihrer Form an die eines Pfaus erinnern, ragen aus dem Hinterleib. Der Hals ist nach hinten gebogen, seine kurzen Federn biegen sich nach oben, ebenso das Gefieder am Hinterkopf. Der dunkle Schnabel des Vogelwesens ist kurz und spitz mit einem Höcker darüber. Auf dem Kopf sitzt eine Federkrone Über dem Vogelwesen befinden sich neun, etwa gleich lange Spalten mit Schriftzeichen. Sie erstrecken sich über die gesamte Breite des Bildes. In einer Art Titelzeile darüber befinden sich mit einem größeren Abstand zu einander drei einzelne Schriftzeichen. Das rechts daneben positionierte Hochformat ist mit dem Buchstaben „B“ bezeichnet. Die Aufteilung des Bildraumes zwischen Schriftzeichen und Illustration ist ähnlich wie bei Bild „A“. Unter einer Art Überschrift aus zwei einzelnen Schriftzeichen erstrecken sich die neun Spalten über die gesamte Breite. Auch in diesem Bild ist das Vogelwesen mit angelegten Flügeln im Profil gezeichnet. Es steht auf einem Bein, das andere hat es angehoben und die Krallen zusammengezogen. Die Füße sind unbefiedert. Der helle Brust- und Bauchbereich ist durch eine klare Linie markiert. An den kleinen gedrungenen Körper schließt ein buschig befiederter emporgereckter Hals an. Das Wesen hält seinen drachenähnlichen Kopf in Richtung seines Rückens gedreht. Federbüschel ragen zu beiden Seiten seines Hauptes wie Ohren in die Höhe. Daneben treten zwei dünne gewellte Hörner hervor, ein weiteres Horn sitzt auf der Schnauze. Das Vogelwesen hat lange dünne Schwanzfedern, die an die eines Fasans erinnern. Sie sind schräg nach oben gerichtet. — — SET 2a+b Huangting dunjia yuanshen jing (Book of the Hidden Period and the Causal [Karma] Body of the Yellow Court) The two black and white images from the 15th century show bird-like creatures under a text in Chinese characters. In the portrait format image marked "A" on the left, the depiction of the creature occupies the lower two-thirds. The creature is shown in profile, striding with its wings spread. It has long, thin, and featherless feet with claws. The underside of its slender and small body is pale. The cover plumage is banded. Long tail feathers, resembling those of a peacock in shape, protrude from the abdomen. The neck is bent backwards, and its short feathers curve upwards, as does the plumage on the back of the head. The bird's dark beak is short and pointed with a hump above it. A crown of feathers sits on top of the head. Above the bird-like creature are nine columns of characters of roughly equal length. They extend across the entire width of the image. In a kind of title line at the top of the page, there are three individual characters at a greater distance from each other. On the portrait format image marked “B” on the right, the division of the pictorial space between the characters and the illustration is similar to that in image "A". Under a kind of heading consisting of two individual characters, the nine columns extend across the entire width. In this image, too, the bird is drawn in profile with its wings spread. It is standing on one leg, the other raised and the claws drawn together. The feet are not feathered. The light breast and belly area is marked by a clear line. The small stocky body is joined by a bushy, feathered upturned neck. The creature holds its dragon-like head turned towards its back. Tufts of feathers rise up on either side of its head like ears. Two thin wavy horns protrude next to it, another horn sits on its snout. The creature has long thin tail feathers that resemble those of a pheasant. They are slanted upwards.](https://comparative-guts.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2a-copy.jpg)