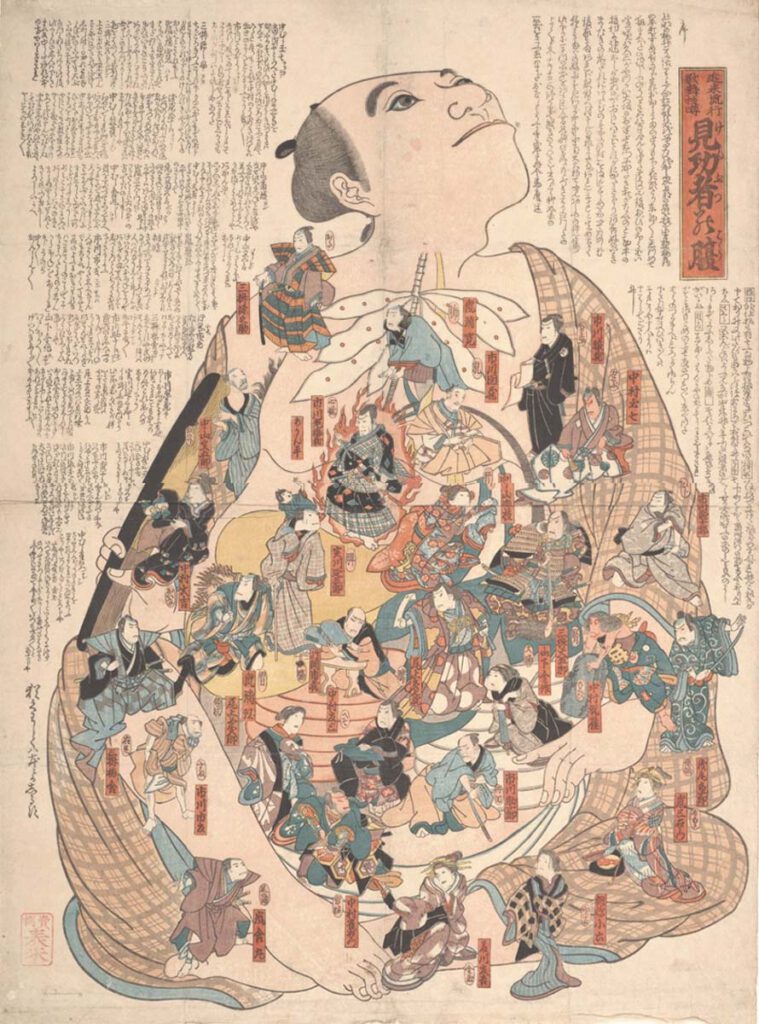

Kinrai ryūkō kabuki uwasa kenbutsu no hara

Kinrai ryūkō kabuki uwasa kenbutsu no hara (A Belly-Survey of the Kabuki Actors Most Talked About Today, late 19th c.) – It is hard, today, to appreciate the glamor of Kabuki actors in early modern Japan. The top stars were celebrated like the movie stars and sports heroes of our own age, their names more […]

Inshoku yōjō kagami

Inshoku yōjō kagami (飲食養生鑑, “Mirror of Dietary Regimen”; ca. 1850) – This popular print proffering advice on food and health highlights another major theme of early modern economic society—an intensified emphasis on hard work, which the economic historian Akira Hayami termed the “industrious revolution.” (5) But it also illustrates two more subtle developments. One is […]

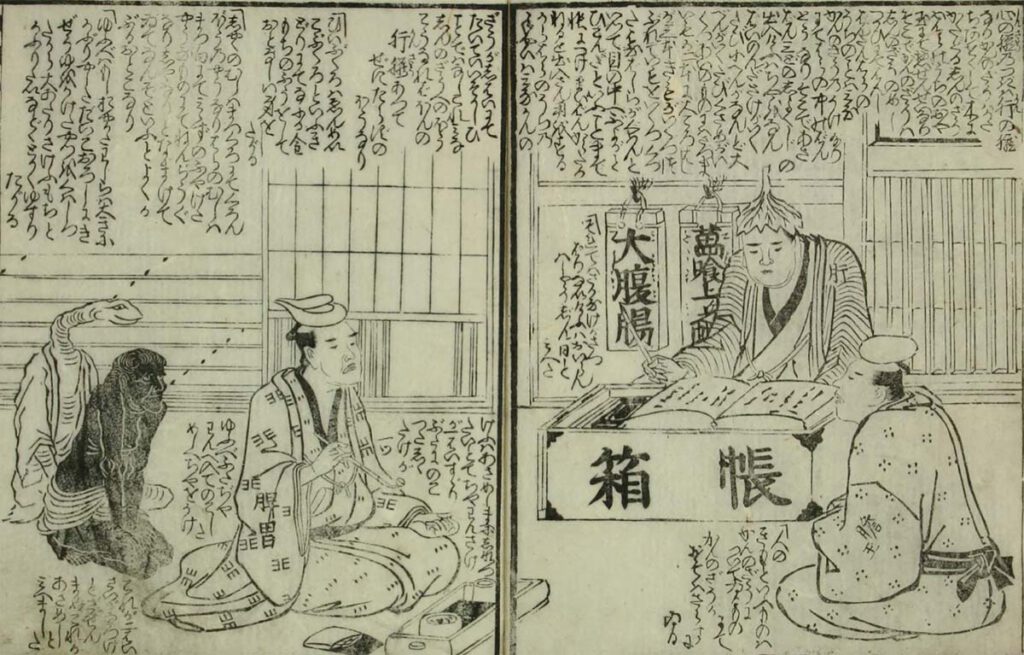

Shiba Zenkō, Jūshi keisei hara no uchi

Shiba Zenkō, Jūshi keisei hara no uchi (十四傾城腹の内, “Inside the bellies of fourteen courtesans”; 1793) – The economic society of early modern Japan not only shaped ways of seeing (fig.1) and touching (fig.2) the guts, but also transformed the imagination of their contents. The title of this work of popular fiction parodies the Jūshi kei […]

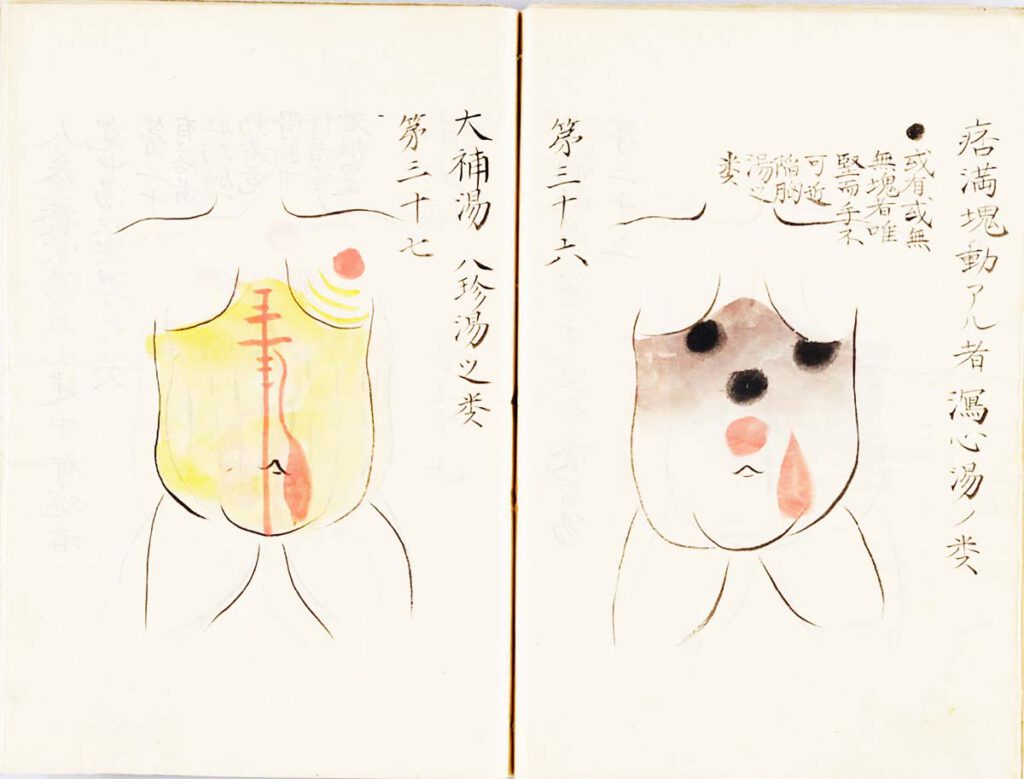

Manase Dōsan 曲直瀬道三, Hyakufuku zusetsu

Manase Dōsan 曲直瀬道三, Hyakufuku zusetsu (百腹図説, “Illustrated Explanations of a Hundred Bellies”; n.d.) – Nothing more directly translated the early modern stress on practical, tangible realities than the Japanese innovation known as fukushin 腹診 (abdominal inspection). Whereas Chinese doctors had relied chiefly on feeling the pulse at the wrist to diagnose diseases, Japanese advocates of […]

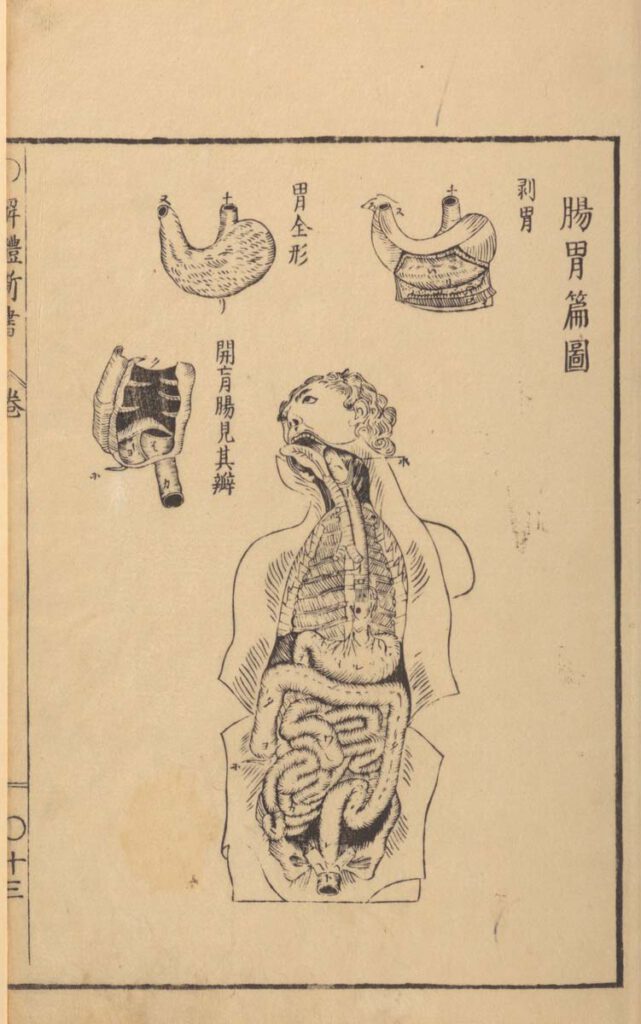

Sugita Gempaku’s Kaitai shinsho

Sugita Gempaku’s Kaitai shinsho (解体新書, “New Book of Anatomy”; 1774) – Sugita Gempaku undertook his epoch-making translation of a Dutch anatomical manual before he could read Dutch. This point is key: What persuaded him of the manual’s truth was not its text, which he initially couldn’t comprehend, but rather, its images, and more specifically their […]