The boundaries of contemporary art are under constant contestation. The questions that continue to unsettle what is inside and what is outside the time of the contemporary and the parameters of art are both highly abstract and deeply material. They bear on the ways that the universalizing discourses and knowledge practices of European modernity have worked with the extractive and disciplinary systems of colonialism, imperialism, and racial capitalism to generate global systems of power and the homogenization of culture. What registers as contemporary art is powerfully shaped by transnational market forces working in tandem with the cultural institutions that confer aesthetic value. These networks of power are also imbricated in patterns of migration under the pressures of war, climate change, and economic inequities. Such entanglements generate a pervasive, generative porosity between traditions while running the constant risk of reproducing the value hierarchies that distort the distribution of planetary resources and fuel unsustainable economies. They make contemporary art a site of extraordinarily complex and unpredictably radical creativity in twenty-first-century global culture.

Within the history of art over the past half century, the body has repeatedly emerged as a field of aesthetic possibilities, particularly for practitioners engaged with feminism, critical Black theory, queer theory, psychoanalysis, new materialism, animal studies, postcolonial and decolonial theory, and disability studies. These theoretical traditions have critically challenged the abjection and objectification of the body within the globally hegemonic philosophical, scientific, and art traditions associated with a cosmo-anthropology of Nature traced back to ancient Greece. In so doing, they have activated the potentialities of embodiment and bodies anew. The guts are metonymic of the body at its most abject, associated with digestion and excretion as well as the matter of the mother and the blurred boundaries of subjectivity within reproduction. In the early twenty-first century, biotechnological developments and the awareness of ecological precarity have also led to an efflorescence of collaborations between artists, activists, scientists, and theorists. These collaborations are remaking the gut as a laboratory of creative hybridizing and cosmological experimentation.

The artists whose work is gathered here approach the gut from many angles: as a model of symbiotic collaboration; a site of unraveling; a challenge to hierarchies of form; a fold in the history of the sexed and raced body to be flattened and reworked; a landscape of processes through which human beings metabolize their world; vessel and loop. In the gut’s ancient communities are coiled new possibilities of living differently in our bodies, together, on a rapidly transforming planet.

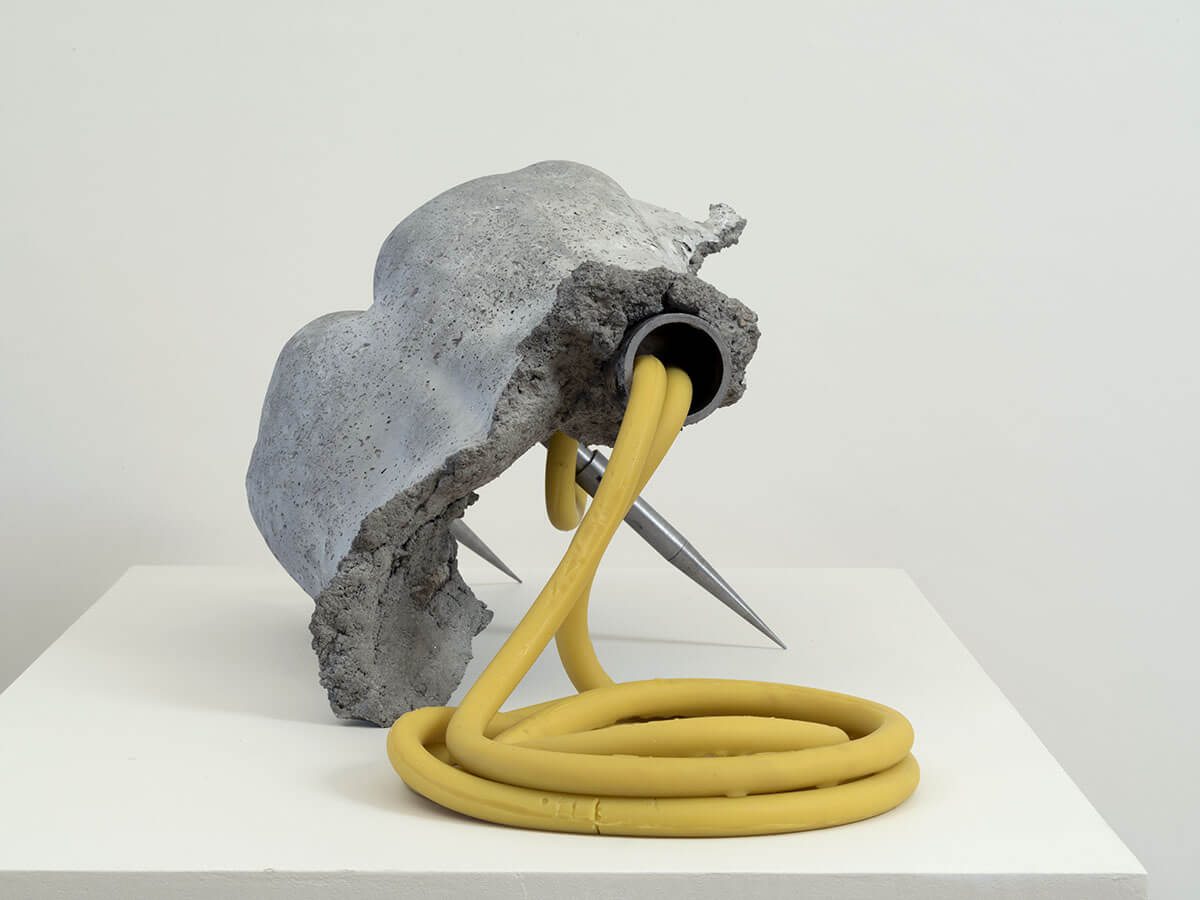

At the same time, as with the collective labor that takes place in the gut, these works break down habits of seeing and knowing as part of a process of reimagining an aesthetics that draws on the manifold potentialities of various bodies as they unfold in new webs of relation. They hold in common an interest in assemblage, gathering materials (dough, fur, rubber, scent, grout) from unlikely places and putting them into unlikely partnerships. These practices of bricolage challenge the classical holism of the Aristotelian body, whose parts read as organs harnessed to the normative realization of a given form of life—above all, “the human.” They ask what else “the human” might be.

The artists included here collaborate with scientists, mechanics, dancers, and other practitioners to think anew about synergistic imagination and interspecies kinship inside and outside conventionally bounded bodies. In so doing, they realize the agency aligned with the artist as both expansively multiple and singularly intentional. Here, the gut is not a metaphor or image of anything. Rather, its metabolic processes are brought forward as co-creators of the work, not in isolation from culture but in visceral relation to layers of lived history. These processes are refracted through materials moving at their own speeds: earth shaped and glazed, dried and fired; compost; silicone rubber snaking around steel.

The hum of matter thus feeds the cosmological energies of these multiform aesthetic projects. It invites us to reimagine the encounter with the artwork as a stimulus to inhabiting our innards otherwise, transforming our practices of consumption, and attending with all our senses to the world around us.