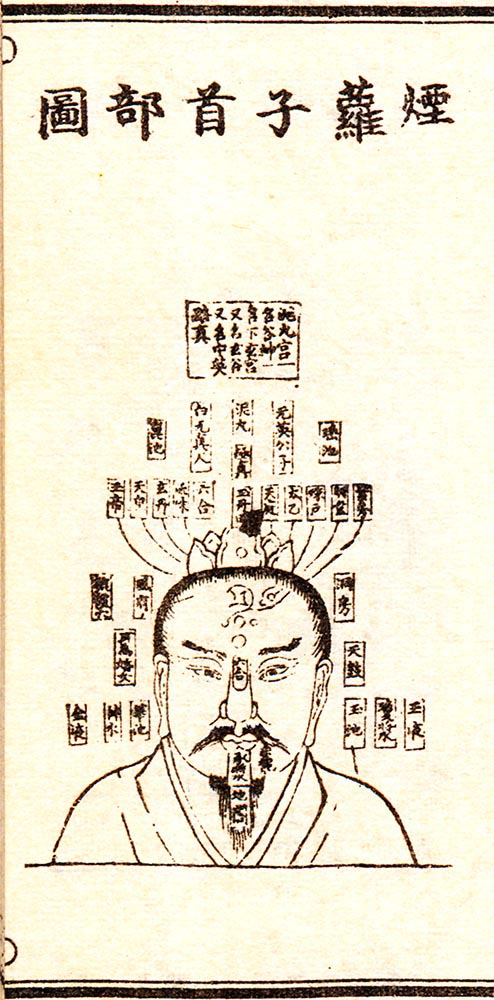

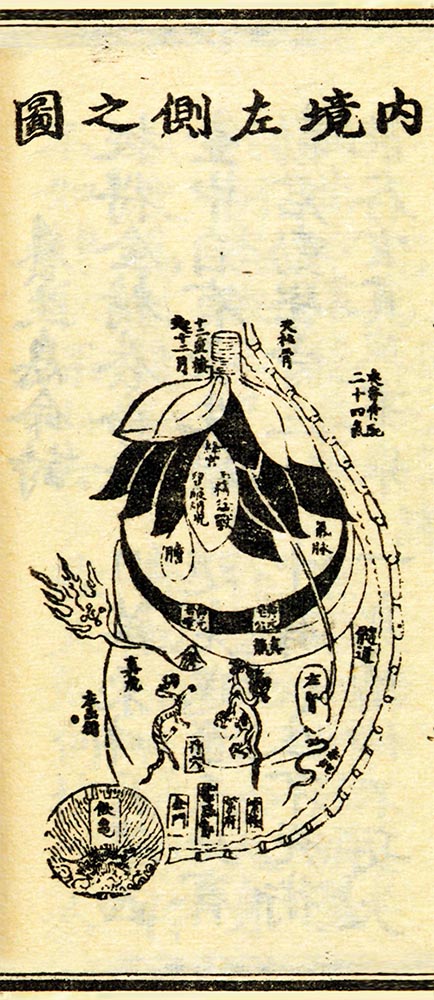

Songs of the Bodily Husk (Ti ke ge 體殼歌) is a composite text attributed to a spurious 10th c. CE figure, Master Yan Luo 煙蘿子 of the Yan 燕 family. He is said to come from the Wangwu region (in today’s northern Henan), known as the author of lost texts on Daoist breathing and meditation techniques, as well as being the creator of the extant body maps under discussion. The work was printed in 1445/1446 CE in the Daoist Canon, fasc. 125, no. 263, juan 18: 1a-10b. In a later version the illustrations are redrawn, and appear with the title Songs of the Bodily Husk of Master Yan Luo (Yan Luo zi Ti ke ge 煙蘿子體殼歌) in Daoist Texts Outside the Canon, vol. 9: 373-378.

The source unites twenty-five sections: a rhymed preamble (§1), two poems (§§2-3), six body maps (§§4-9), the Treatise on the Inner Realm by Superintendent Zhu (Zhu ti dian nei jing lun 朱提點內境論), which includes critical comments on the body maps (§10), a meditation manual and instruction called Master Yan Luo’s Guideline on Inner Observation (Yan Luo zi nei guan jing 煙蘿子內觀經) (§11). Short elucidations treat topics of physiological alchemy (nei dan 內丹), the head and brain (§§12-14, 20-24), or give summary treatises on the five storehouses (§§15-19). Talisman illustrations conclude the text (§25).

Several kinds of knowledge fields mingle, interact and lead to new questions. The self-cultivation practice called ‘inner observation’ (nèi guān 內觀) had opened a profound and detailed inner world, each adept could relate to in their practice.

The body maps are profusely labelled. More than 110 labels enable one to learn a linguistic and visual glossary of technical terms. It thus emerges a thick intertextual network referencing aspects of self-cultivation techniques that help to prescriptively structure one’s bodily awareness. Terms used in medicine only in part overlap with everyday words common for animal and human body parts.

Two emic categories classify the body map series: four are of the ‘Maps of Master Yan Luo’ (Yan Luo zi tú 煙蘿子圖) type, two are ‘Five Storehouses Maps’ (wǔ zàng tú 五臟圖). Both kinds of illustrations were used in visualisation exercises in order to guide one’s bodily awareness. Painted on hanging scrolls these images even became lifestyle objects, found in the households of literati and officials.

Superintendent Zhu is keenly aware of the clash between field dissection of dead bodies and inner observation of one’s own experiences, as he asks rhetorically: