Ranging from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, these images of the viscera were produced for a wide range of purposes: for religious contemplation and for social commentary, as explanatory illustrations of anatomy and of pathology, and as records of anatomical instruction. While reciting a prayer for the safety of their “body and soul”, the owner of a fifteenth-century decorated prayer book could contemplate the equanimity with which St Erasmus endured the removal of his intestines

(fig. 1), a sign of the power of his faith in God.

The great length of the intestines is indicated as they are wound around a windlass above the saint, and in

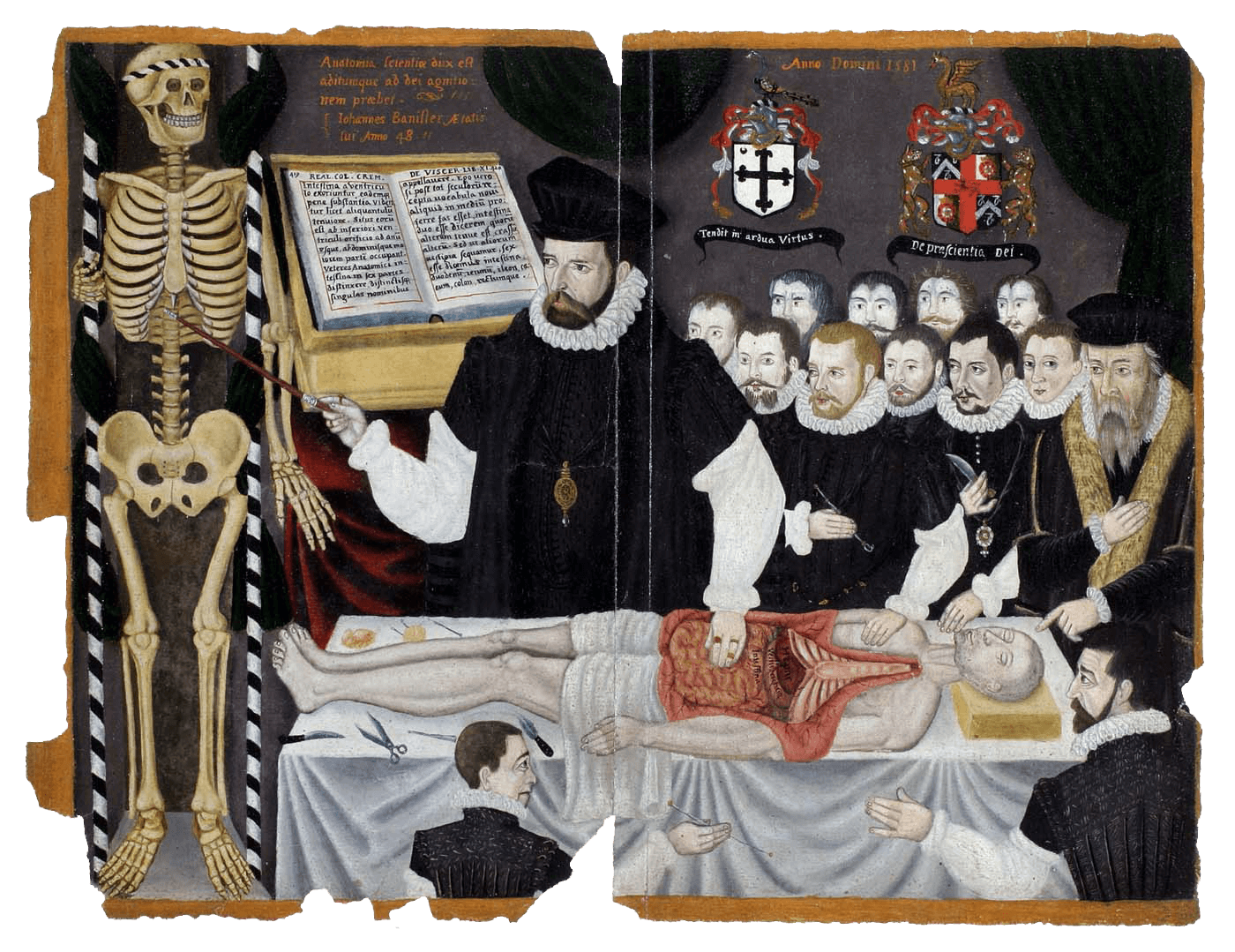

fig. 4, another scene of disembowelment. In this period in Europe, human dissection was a standard element of medical education, with lectures delivered in front of the open body

(figs 3–

4), usually that of an executed criminal. The intestines and stomach were typically the first parts to be removed, as these were the soonest to putrefy. In dissections, knowledge of the body was gained by sight and by touch and, often, by the reading of anatomy texts, like that seen open in the background of John Banister’s late sixteenth-century lecture on the viscera

(fig. 3). The painting commemorates the lecture on the viscera given to the Company of Barbers Surgeons in London and was once part of a manuscript with depictions of anatomy and of surgical instruments.

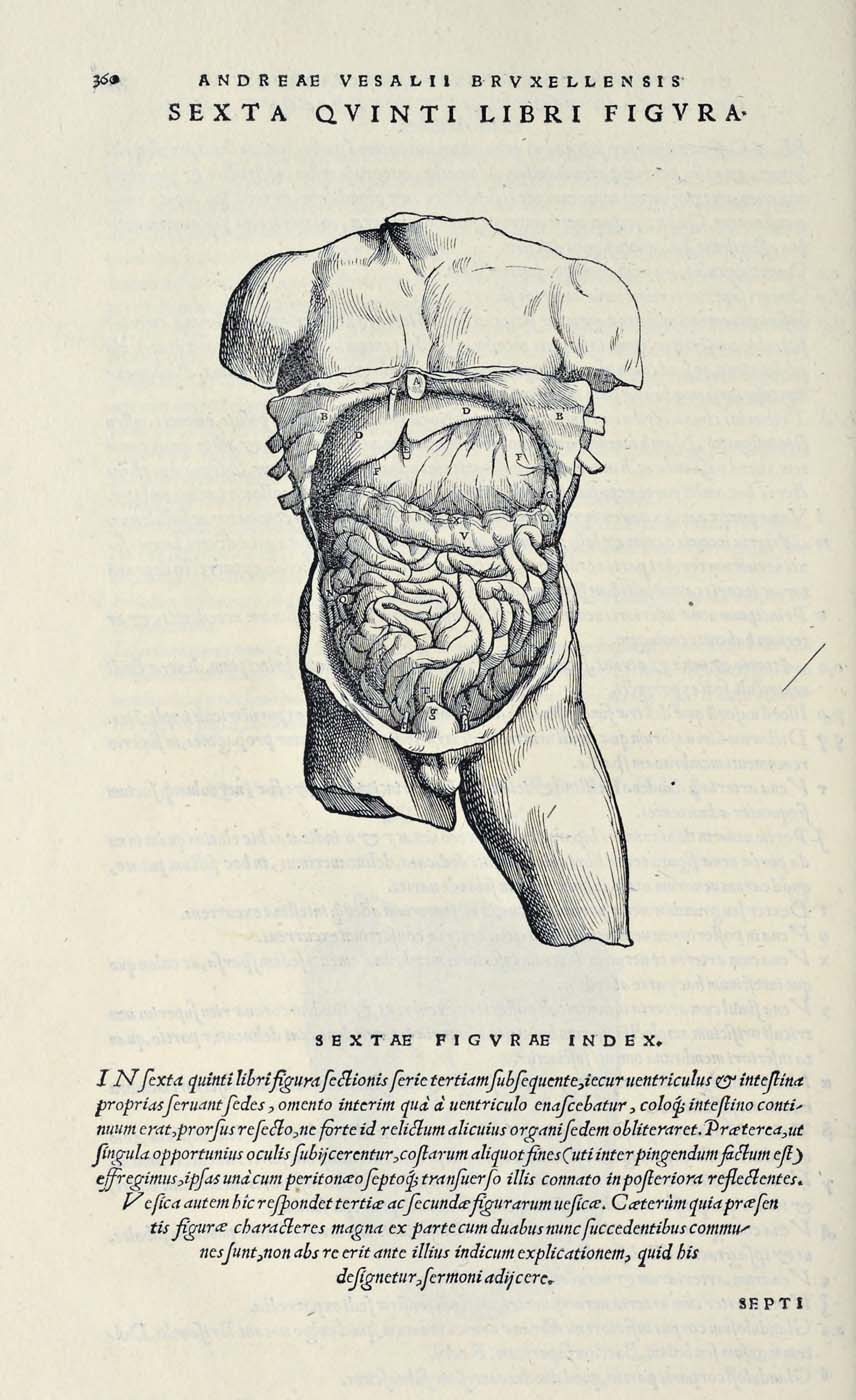

The woodcut from Vesalius’s

De fabrica (fig. 2) is one in a sequence in which the abdomen is gradually dissected on the page. All the parts are identified in an explanatory text, keyed to the lettering, and the image is also referenced in the main text. Three centuries later, the use of colour printing is used to its full advantage in Cruveilhier’s

Anatomie pathologique (fig. 5) to capture the ravages of cancer in pathological images of the stomach which serve as illustrations linked to case histories, including specific clinical signs and patient’s symptoms.