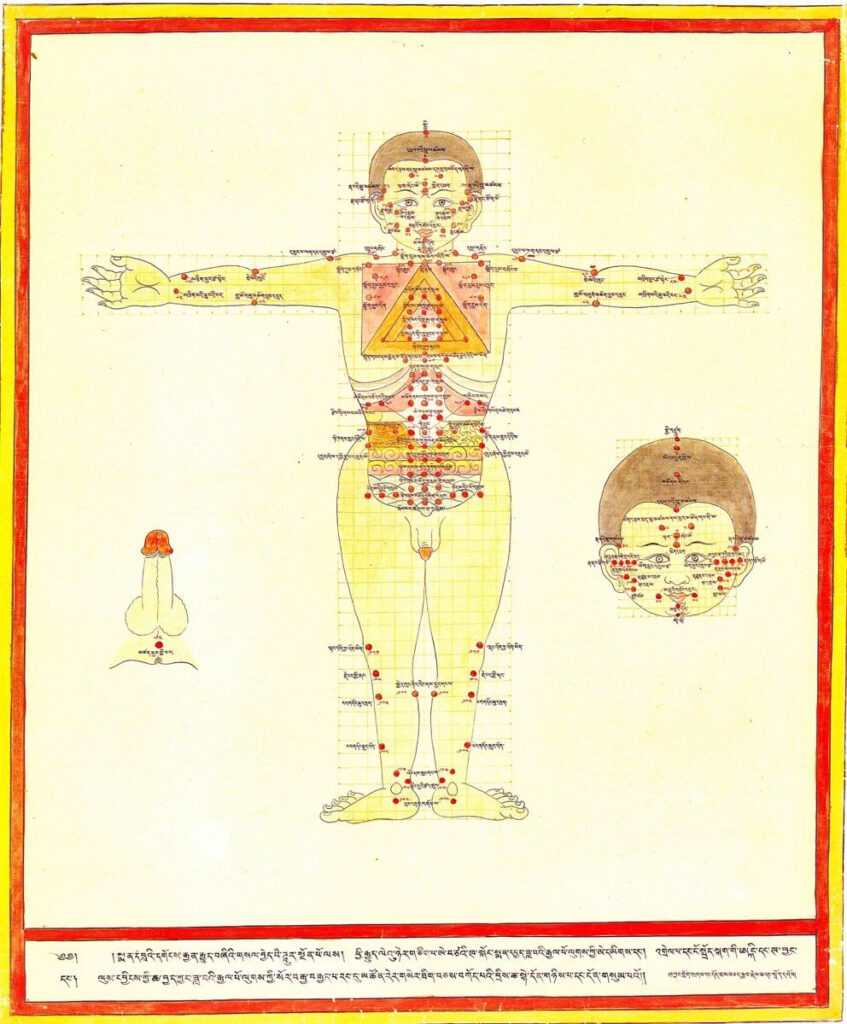

Sugita Gempaku’s Kaitai shinsho

Sugita Gempaku’s Kaitai shinsho (解体新書, “New Book of Anatomy”; 1774) – Sugita Gempaku undertook his epoch-making translation of a Dutch anatomical manual before he could read Dutch. This point is key: What persuaded him of the manual’s truth was not its text, which he initially couldn’t comprehend, but rather, its images, and more specifically their […]

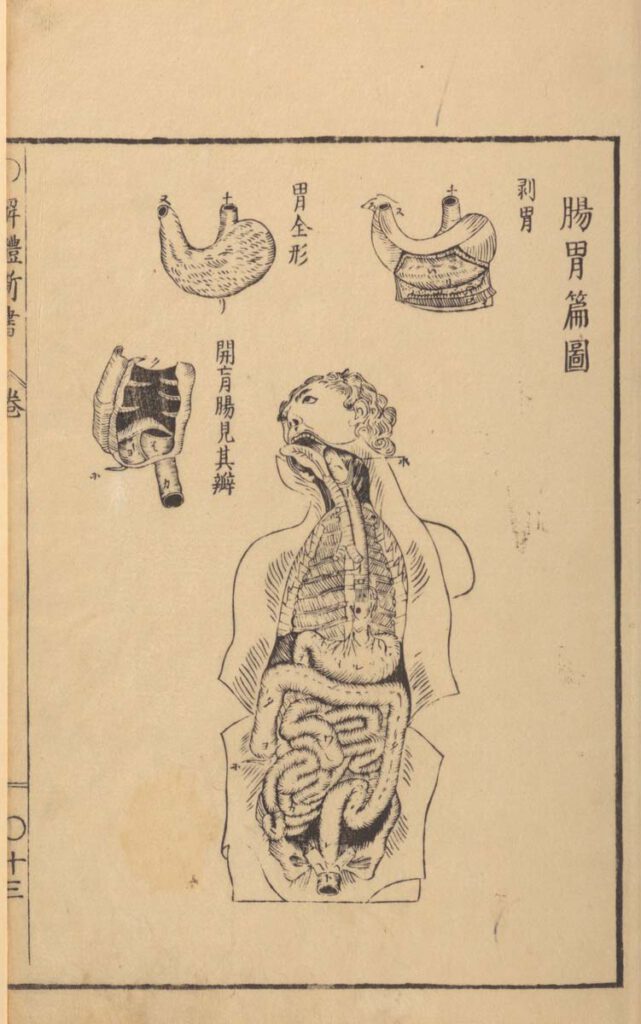

Reproduced artwork detailing small and large intestines with Tibetan and Latin labels

Reproduced artwork detailing small and large intestines with Tibetan and Latin labels Reproduced artwork detailing small and large intestines with Tibetan and Latin labels. Contemporary knitwork. © Katharina Sabernig – Tibetan classical medical vocabulary is already rich in anatomical terms. When encountering biomedical concepts, new terms were coined in the Tibetan language. Nevertheless, many historical […]

Knitted artwork of guts based on Tibetan medical painting at Atsagat Monastery, Republic of Buryatia, Russia.

Knitted artwork of guts based on Tibetan medical painting at Atsagat Monastery, Republic of Buryatia, Russia Knitted artwork of guts based on Tibetan medical painting at Atsagat Monastery, Republic of Buryatia, Russia. © Katharina Sabernig – In Buryatia, an ethnically Mongolian region belonging to Russia, Tibetan medical knowledge encountered biomedical knowledge in the early twentieth […]

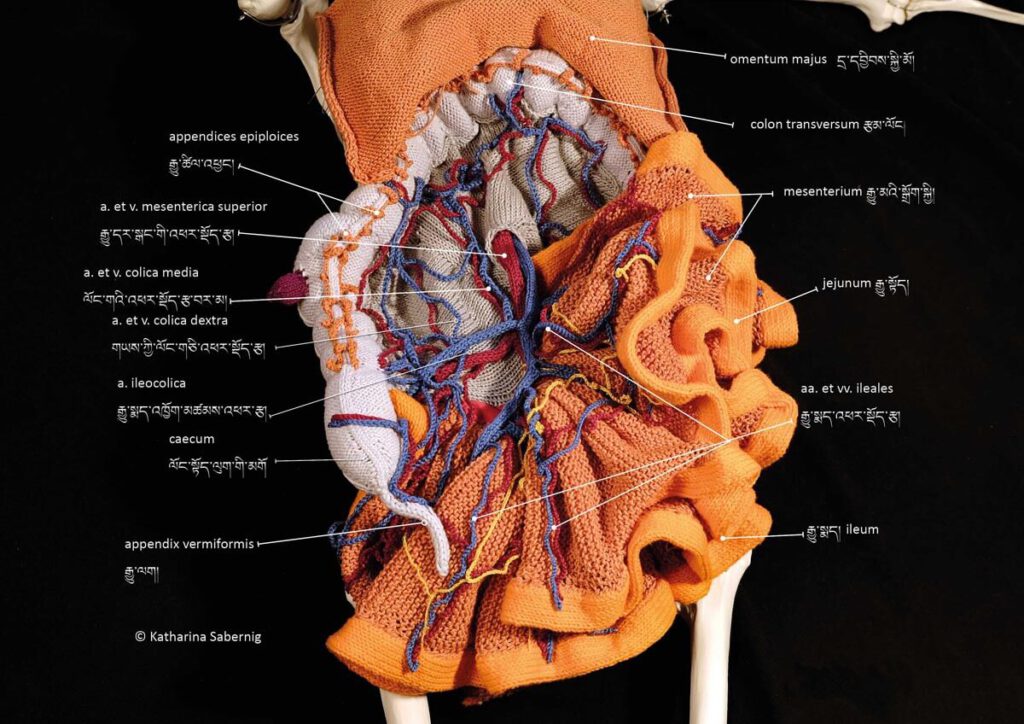

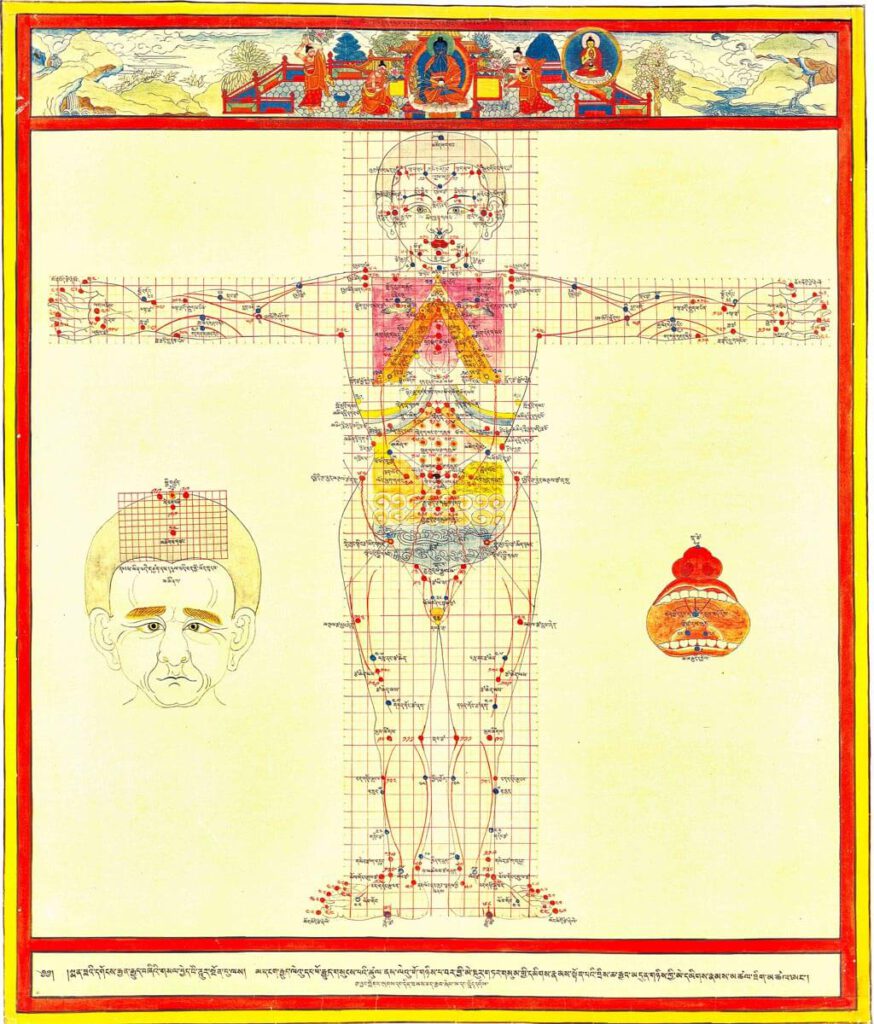

Moxibustion points according to Medical Arts of the Lunar King, Sowa Rigpa intersections with Chinese and Indian medical canons

Moxibustion points according to Medical Arts of the Lunar King, Sowa Rigpa intersections with Chinese and Indian medical canons 20th century reproduction of 17th century CE painting. Held in Ulan-Ude, Republic of Buryatia, Russia. – Moxibustion is a treatment particularly indicated for metabolic conditions (ma zhu ba) and weak digestive fire (me drod nyams pa) […]

Treatment points for moxibustion, venesection, and surgery

Treatment points for moxibustion, venesection, and surgery 20th century reproduction of 17th century CE painting. Held in Ulan-Ude, Republic of Buryatia, Russia. – This painting depicts the anterior view for the three types of external therapy treatment points: moxibustion, venesection, and surgical puncture. Moxibustion points are vermillion numbers and lines, venesection points are blue lines […]

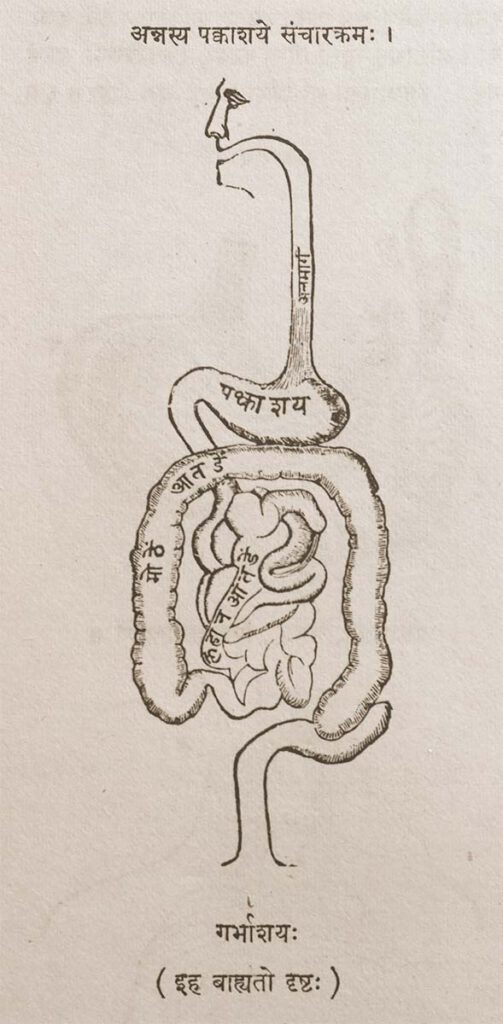

Food’s Course of Movement in the Intestines (engraving)

Food’s Course of Movement in the Intestines (engraving) Provenance: Printed Book, page 44. Anglicized Bibliographic data The Śārṅgadhara-saṃhitā by Paṇḍit Śārṅgadharāchārya, son of Paṇḍit Dāmodara with the commentary Aḍhamalla’s Dīpikā and Kāśīrāma’s Gūḍhārtha-Dīpikā. Ed. Paṇḍitaparaśurāmaśāstri. Bombay: Pāndurang Jāwajī, Nirṇaya-Sāgar Press, 1931. Sanskrit Title and Author in Roman font śrīmatpaṇḍitadāmodarasūnu-śārṅgadharācāryaviracitā . śārṅgadharasaṃhitā . bhiṣagvarāḍhamallaviracitadīpikā-paṇḍitakāśirāmavaidyaviracita-gūḍhārthadīpikābhyāṃ ṭīkābhyāṃ saṃvalitā […]

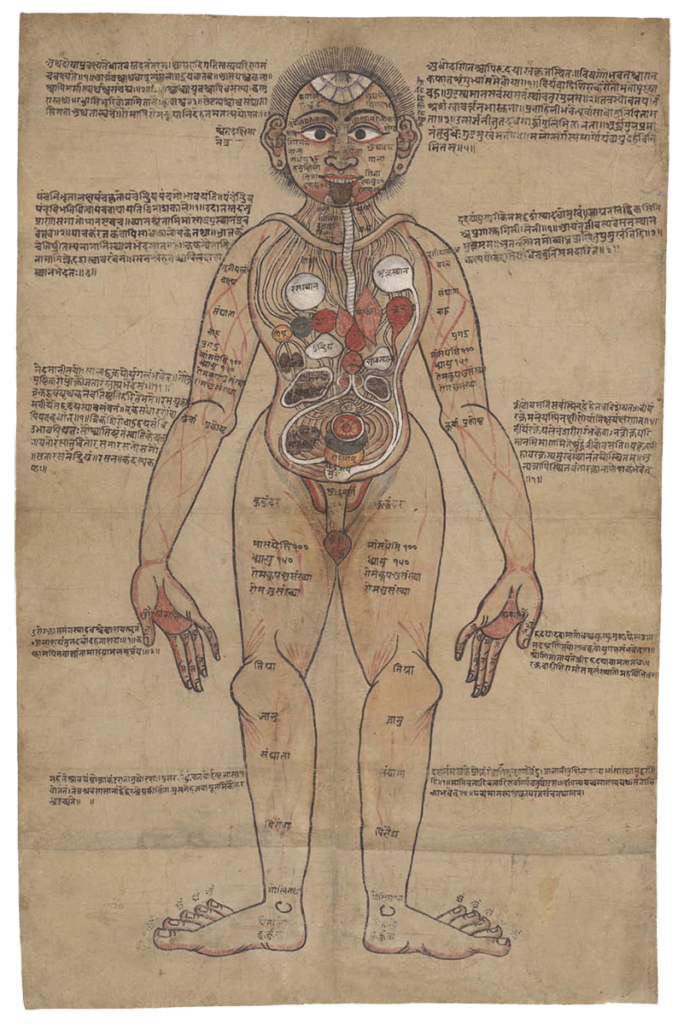

Indian anatomical painting

Indian anatomical painting Circa eighteenth century, western India. An old-Gujarati manuscript (circa 1900?). (Wellcome MS Indic d 74. Photo Wellcome Library, London.) Source: Wellcome Collection CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 – Premodern anatomical images in India were influenced by Persian drawings on anatomy, particularly during the Mughal dynasty’s reign in north India from the sixteenth to eighteenth […]

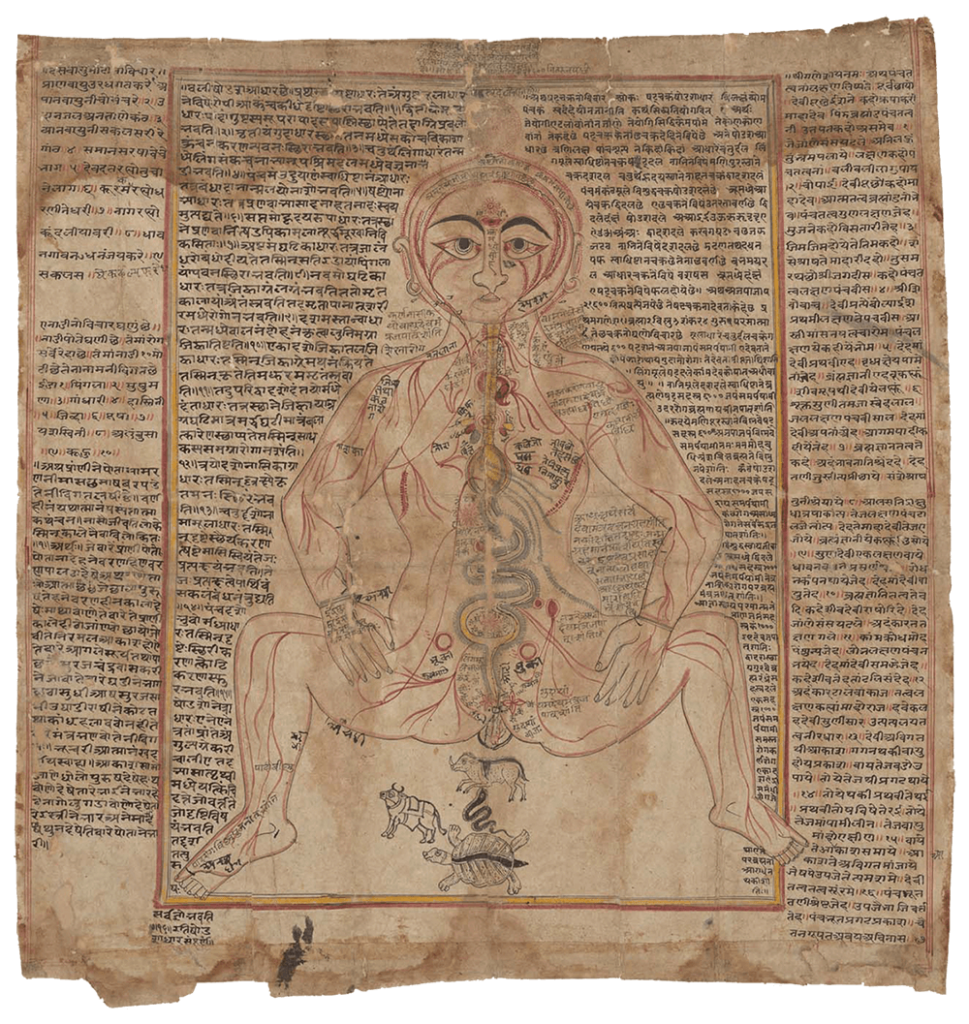

A human anatomical figure

A human anatomical figure Drawing, Nepalese, ca. 1800 (?) Source: Wellcome Library no. 574912iWellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. – Although India has thousands of manuscripts of premodern medical texts, only a handful contain anatomical illustrations. Text was crucially important for transmitting medical teachings. Figure 1 combines text with an illustration of the body and its […]

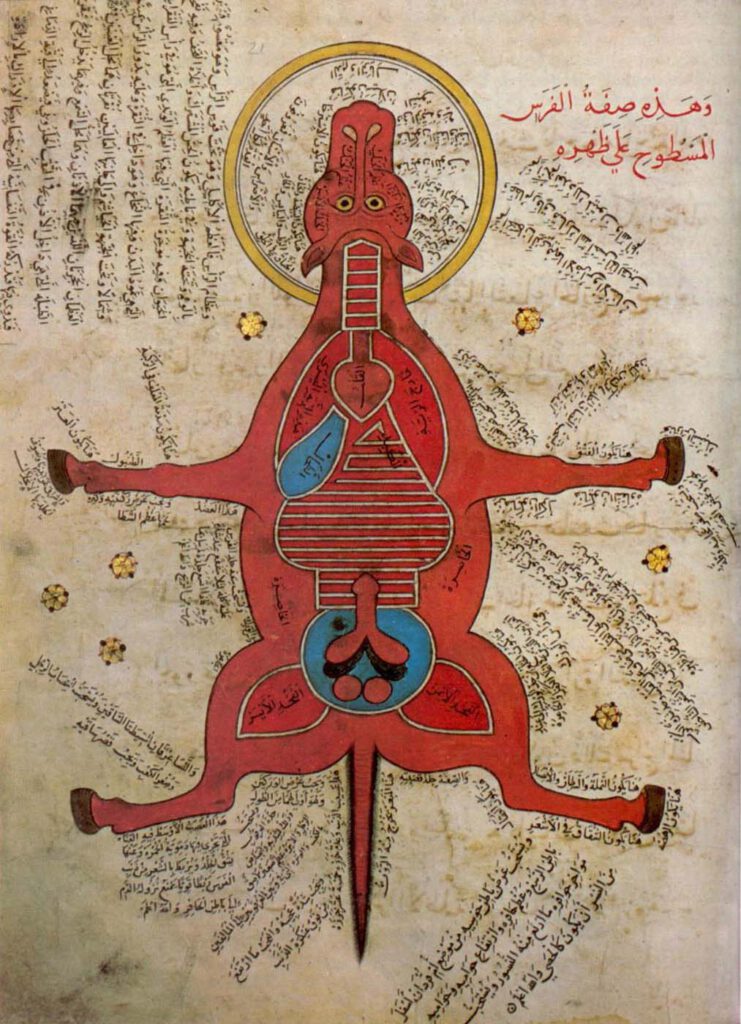

Anonymous, K. Sharḥ al-Maqāma al-Ṣalāḥiyya fī l-Khayl wa-al-Bayṭāra

Anonymous, K. Sharḥ al-Maqāma al-Ṣalāḥiyya fī l-Khayl wa-al-Bayṭāra (Commentary on the Maqāma Ṣalāḥiyya on Horses and Venterinary) Istanbul University Library MS 4689 – Egypt, 15th c. – Hyppiatry has a long tradition in Islamic literature. Works dealing with horses may adopt different literary genres and cover a wide range of disciplines, from veterinary sciences to […]

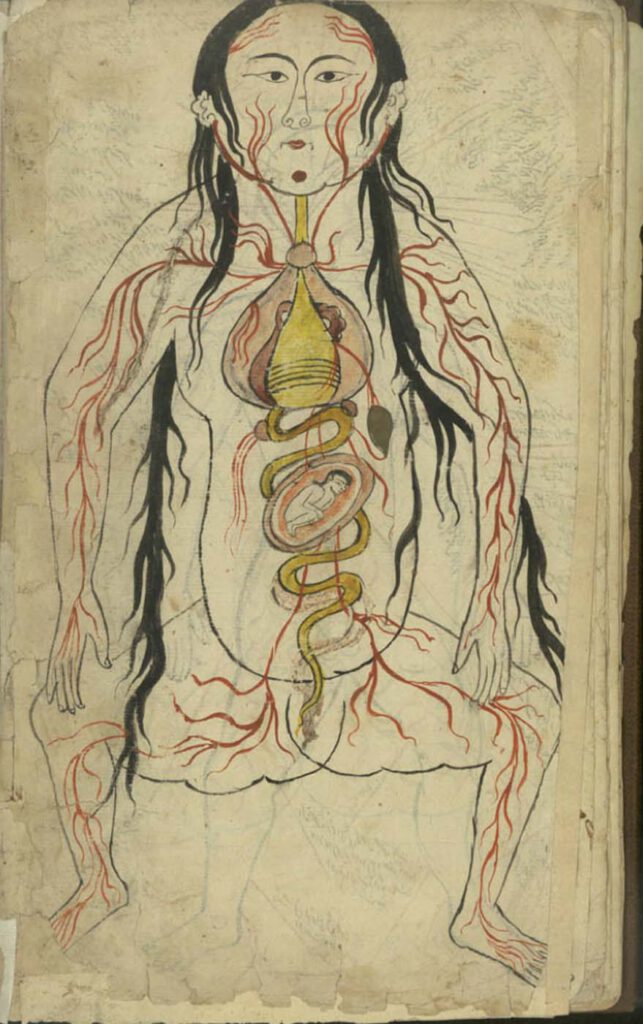

Representation of a woman with the distribution of the blood vessels and the internal organs (f. 15v)

Representation of a woman with the distribution of the blood vessels and the internal organs (f. 15v) Manṣūr ibn Ilyās (fl. 14th c.), Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān. Images from: Teheran MS Majlis 7430. Undated. This image represents the heart, lungs, liver, esophagus/larynx, stomach, intestines, kidneys, and spleen). As in the male representation, the organs involved in […]