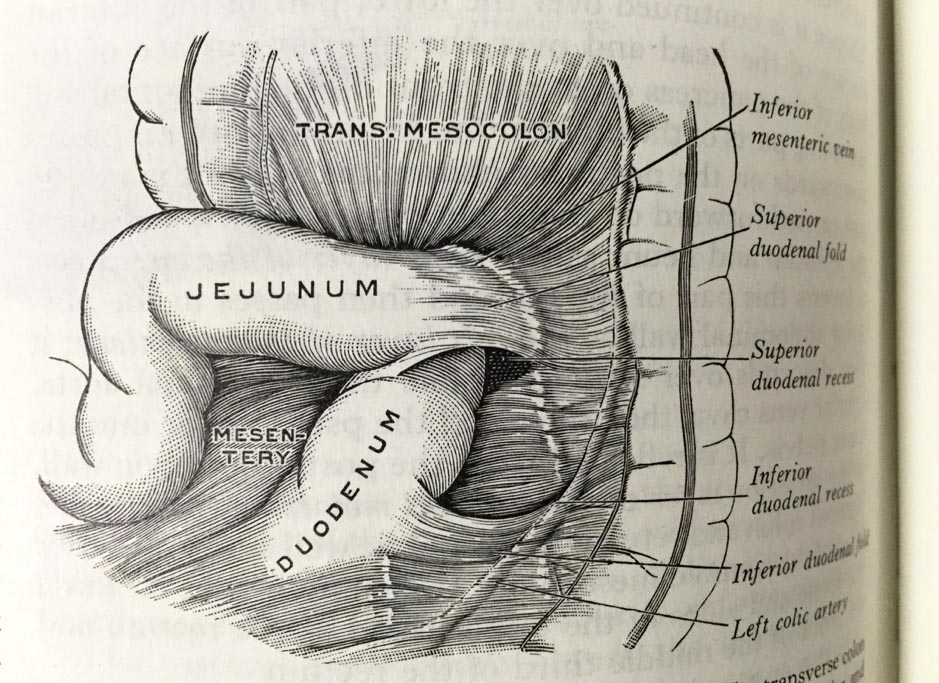

Henry Gray (anatomist) and Henry Vandyke Carter (artist), Fig. 1005, Superior and inferior duodenal fossæ.

Henry Gray (anatomist) and Henry Vandyke Carter (artist), Fig. 1005, Superior and inferior duodenal fossæ. Gray’s Anatomy Descriptive and Applied. A New American Edition (1913), p. 1265.Private collection: Nina Sellars. Photographer: Nina Sellars. – Giving thoughtful attention to the physical qualities of the classical anatomical atlases brings our awareness not only to their content and […]

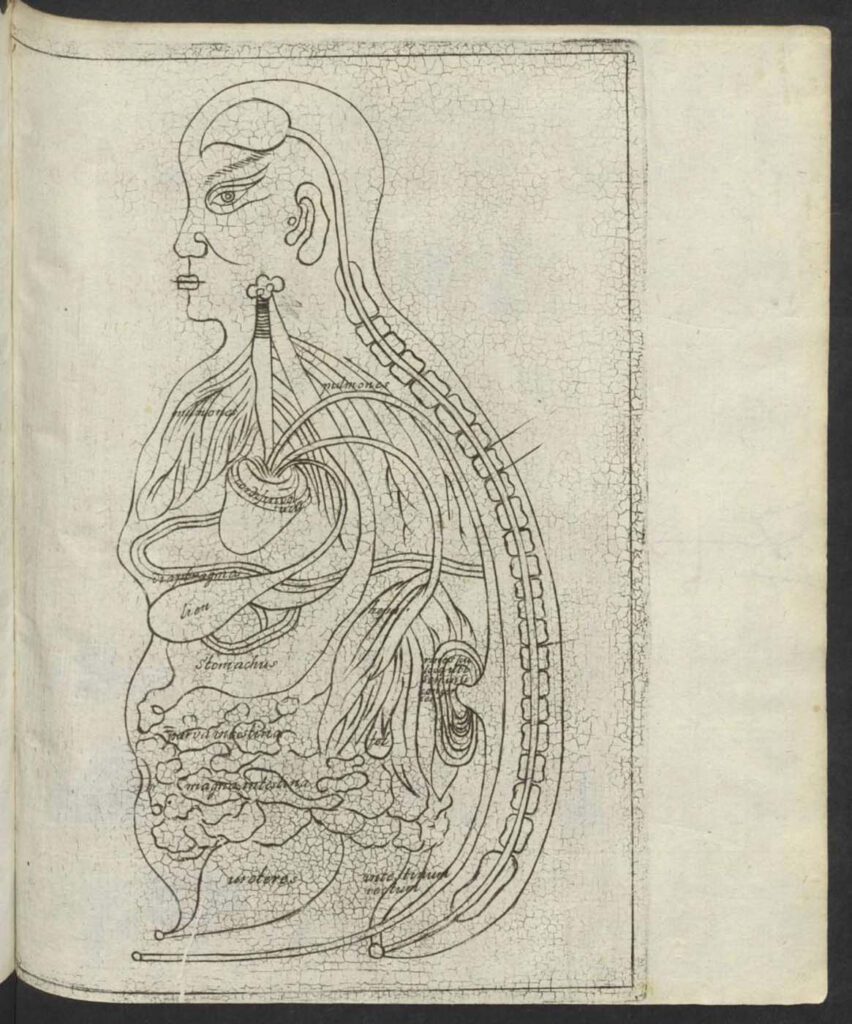

1682 Specimen Medicinae Sinicae, unknown artist

1682 Specimen Medicinae Sinicae, unknown artist This “Viscera Man” was also based on a Chinese source (Image 1) but was printed in the 1682 Specimen Medicinae Sinicae. The anonymous artist retained the Chinese original’s flat rendering (Image 1) rather than the three-dimensional rendering of Christian Mentzel’s sketch (Image 3) and the sketch (Image 4) in […]

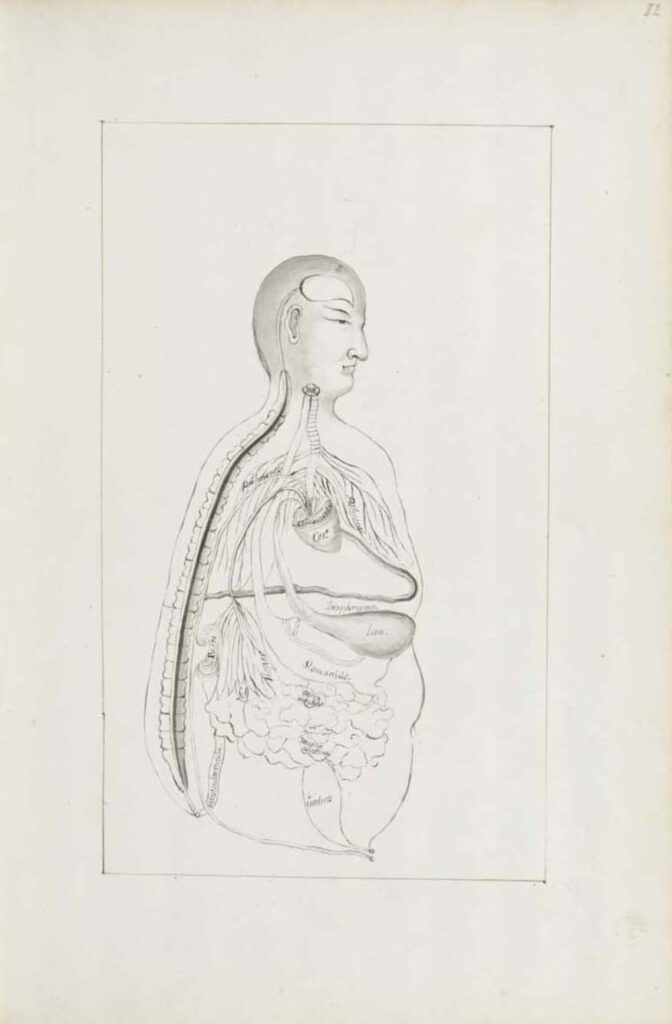

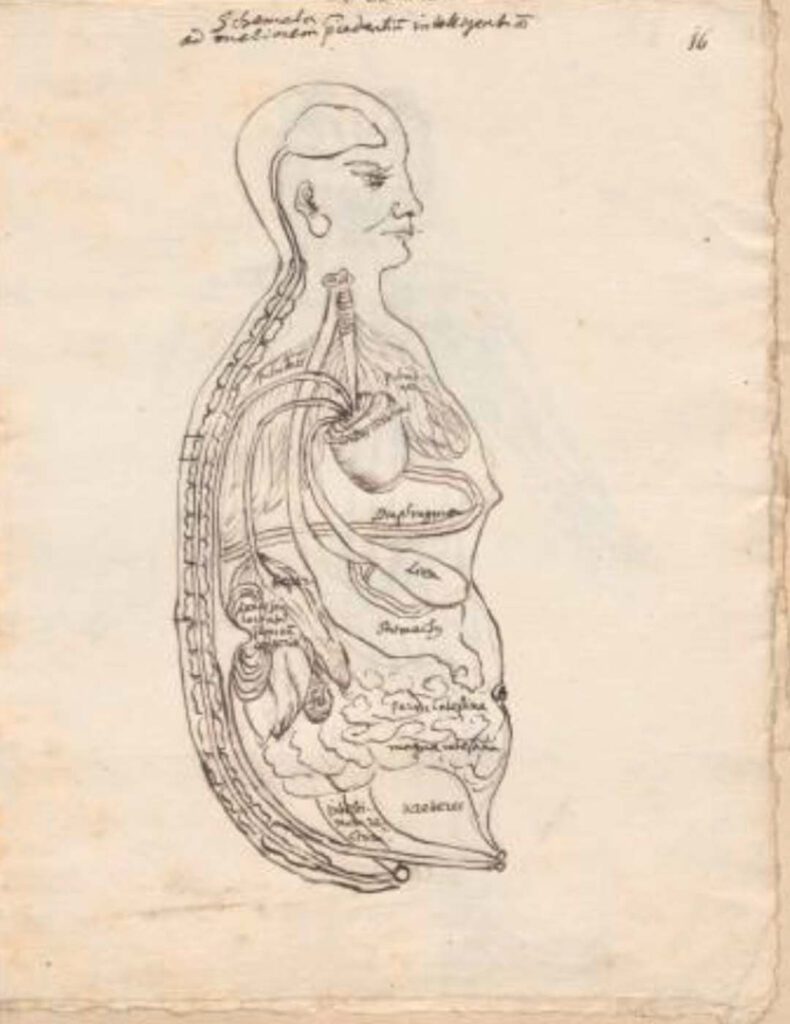

Ca. 1660s-1681c. Lat. Fol. 95, unknown artist

Ca. 1660s-1681c. Lat. Fol. 95, unknown artist This sketch of the “Viscera Man” was also based on a Chinese source (image 1), however, the artist remains anonymous. It was included in the only known extant manuscript (Ms. Lat. Fol. 95 preserved in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin) of the 1682 printed Specimen Medicinae Sinicae. It illustrates […]

Ca. 1681 Ms sin. 11, part 3 by Christian Mentzel

Ca. 1681 Ms sin. 11, part 3 by Christian Mentzel The personal physician to the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenberg and curator of his library, Christian Mentzel (1622-1701), sketched this “Viscera Man” based on a Chinese source (Image 1). Both Mentzel’s sketch (Image 3) and the printed 1597 original (Image 1) are included in […]

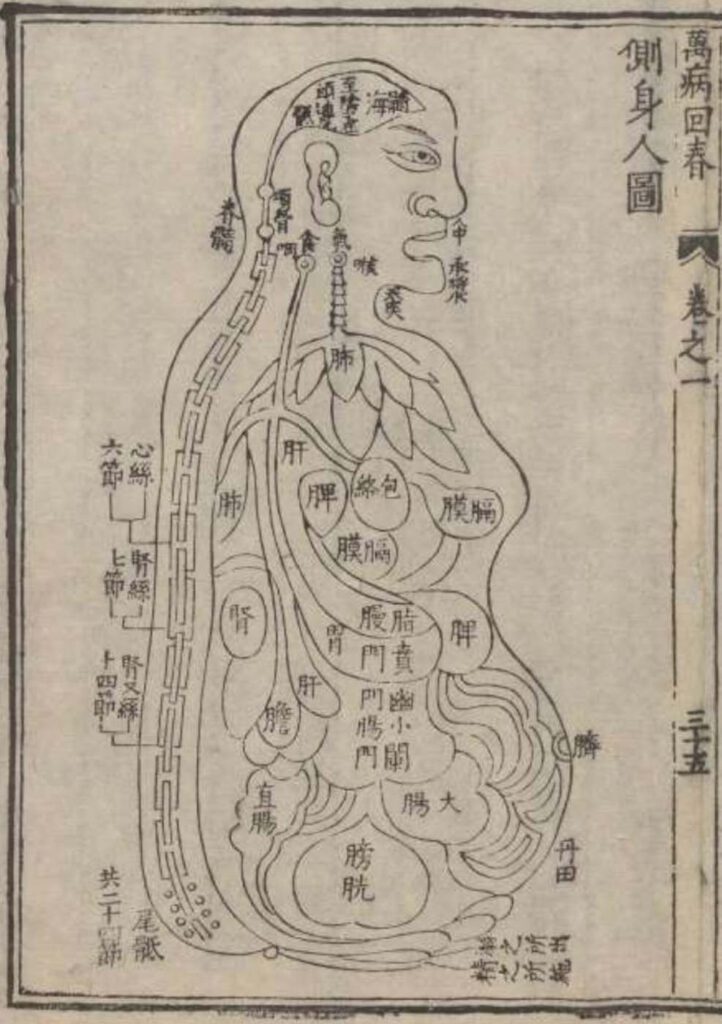

1597 reprint of Wanbing huichun “Diagram of Man’s Side-Body”

‘Diagram of Man’s Side-Body’ in 1597 reprint of Wanbing huichun (Ceshen ren tu 側身人圖). This version of the “Viscera Man” was printed in a 1597 reprint of the Chinese medical text Myriad diseases ‘Spring Returned’ (i.e., ‘cured’) (Wanbing huichun 萬病回春) that is preserved in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. – This 1597 reprint of a “viscera […]

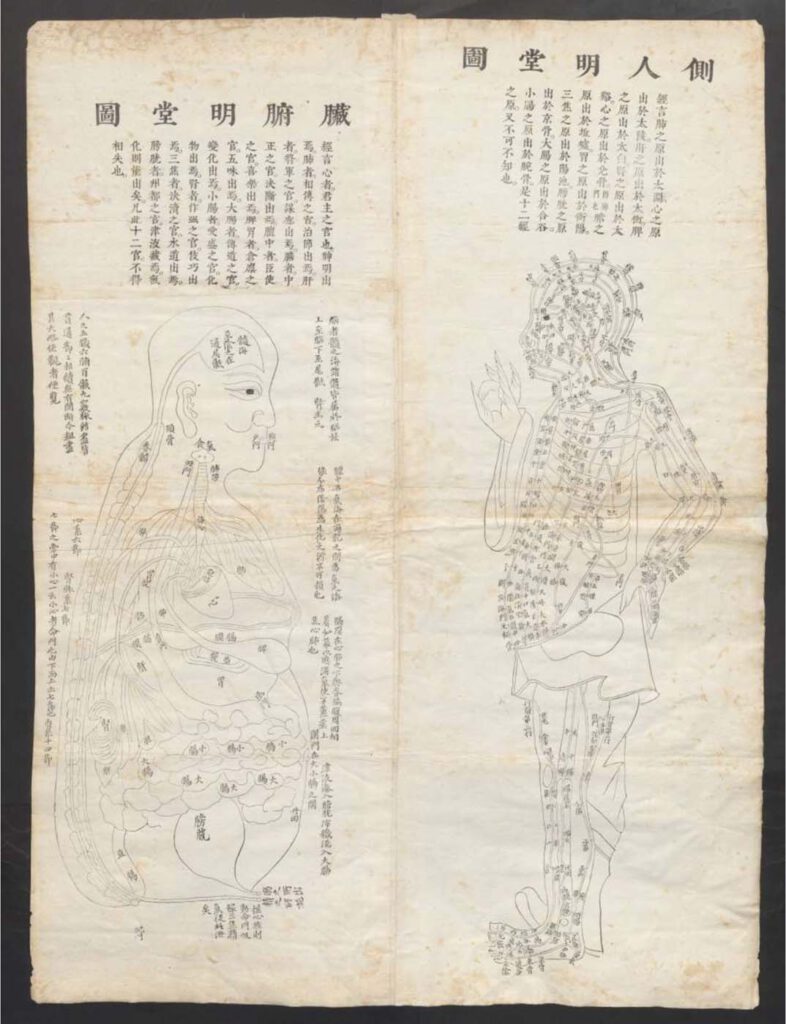

Published in 1597 reprint of a 1565 Yixue gangmu, preserved in Ms sin. 11, part 1, “Enlightened-Hall Diagram of the Viscera”

‘Enlightened-Hall Diagram of the Viscera’, in 1597 reprint of a 1565 Yixue gangmu, preserved in Ms sin. 11, part 1 (Zangfu Mingtang tu 臟腑明堂圖). This fold-out plate (ca. 79cm x 58cm) of a “Viscera Man” has been inserted into a manuscript (ms. sin. 11) preserved in Biblioteka Jagiellońska Kraków, Poland, digitalized by the Staatsbibliothek in […]

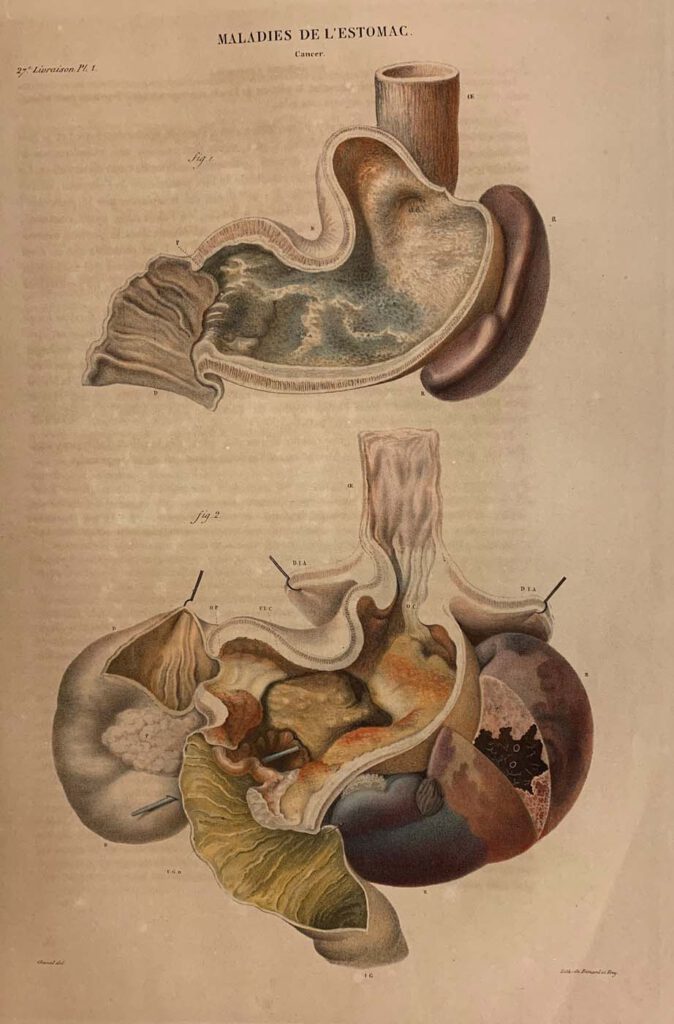

Diseases of the Stomach (cancer)

Diseases of the Stomach (cancer) lithograph printed by Benard and Frey after Antoine Touissant de Chazal (French, 1793-1854). From Jean Cruveilhier, Anatomie pathologique du corps humain (Paris: J. B. Baillière, 1829-1842), vol. 2, part 27, pl. 1. Huntington Library, Art Museum and Gardens, San Marino, California, RB 632011. – By the nineteenth century, publishing technology […]

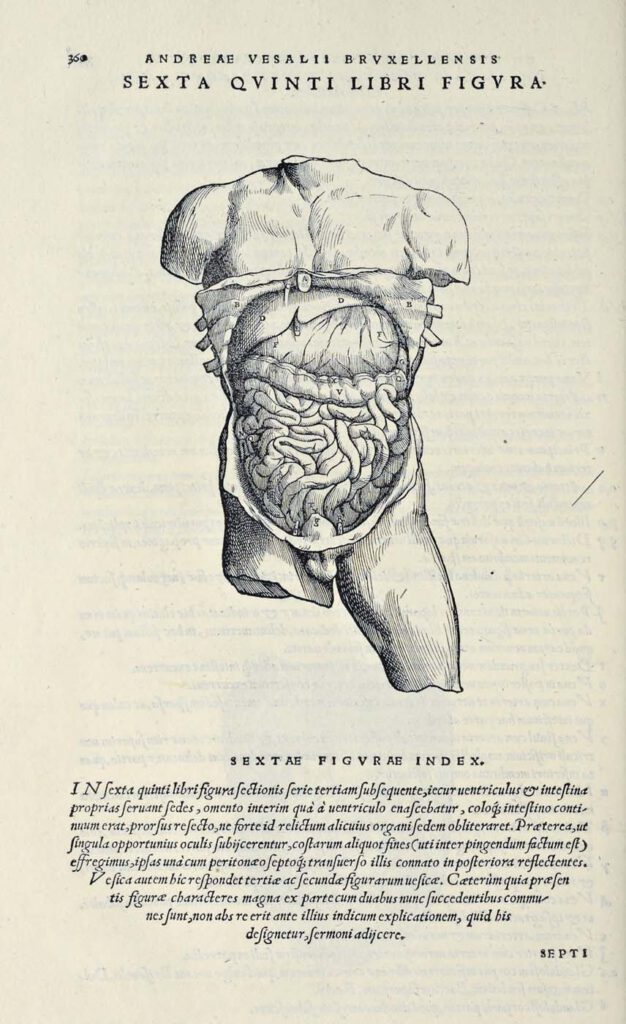

Abdominal Dissection

Abdominal Dissection woodcut after Jan Steven van Calcar (North Netherlandish, ca. 1515– ca. 1546). From Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel: J. Oporinus, 1543), bk. 5, p. 360 [460], fig. 6. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 84-B27611 – Ribs have been broken and the skin peeled back to display the liver, stomach, […]

A female ‘open torso’ figurine

A female ‘open torso’ figurine Nottingham Castle Museum – This female figurine was discovered at the sanctuary of the Graeco-Roman goddess Artemis/Diana Nemorensis at Lake Nemi in Italy in 1885. It was excavated and recovered from a sacred pit where it had been ritually disposed of sometime in antiquity after it had ceased to be […]

A polyvisceral plaque

A polyvisceral plaque Museo Nazionale Etrusco Di Villa Giulia – This Etruscan polyvisceral plaque from Tessennano in Latium in Italy is thought to date from around 400 BCE. Anatomical votives like these were deposited in sanctuaries and temples as offerings to the gods, generally interpreted as a gesture of gratitude for some manner of divine […]