16 CE-1477 CE

China

Vivienne Lo

UCL History

Introduction

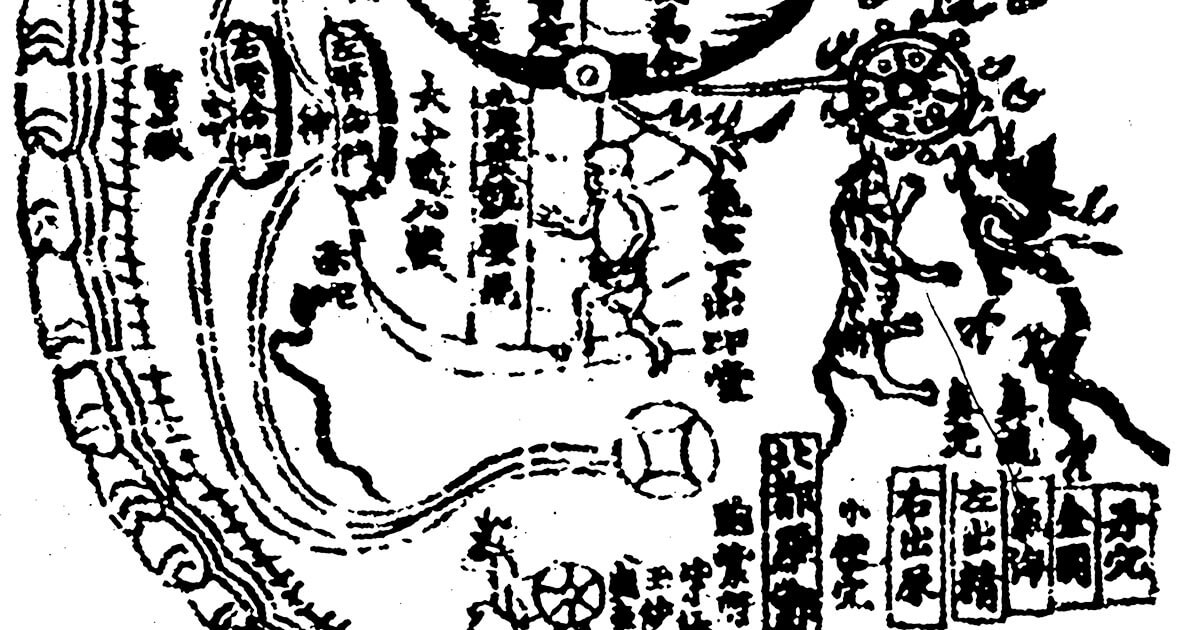

State sponsored anatomical investigations of cadavers were carried out in China on executed criminals in 16 CE between the Western and Eastern Han dynasty, and then again in 1041 CE. In the Han dissection, the human organs were weighed, and their guts measured. Details were then recorded in classical medical treatises such as the Huangdi neijing 黃帝內經 (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic) which was eventually compiled into at least four recensions. In the latter case, the diagrams of the executed rebel fighter Ou Xifan 歐希範 were ultimately integrated into a set of medical illustrations with distinctive Daoist elements, Li Jiong’s Neijing tu 内景圖 (Chart of the Inner Landscape, (1269)). Since nowhere in the pre-modern world could deep abdominal dissection be therapeutically practical, anatomical knowledge was reinvented over the millennium between Han and Song (960-1279 CE) for a variety of purposes, according to evolving models of the human body. We can also trace versions of this knowledge through images that travelled west to Central Asia and east to the lands and islands that are now Korea and Japan.

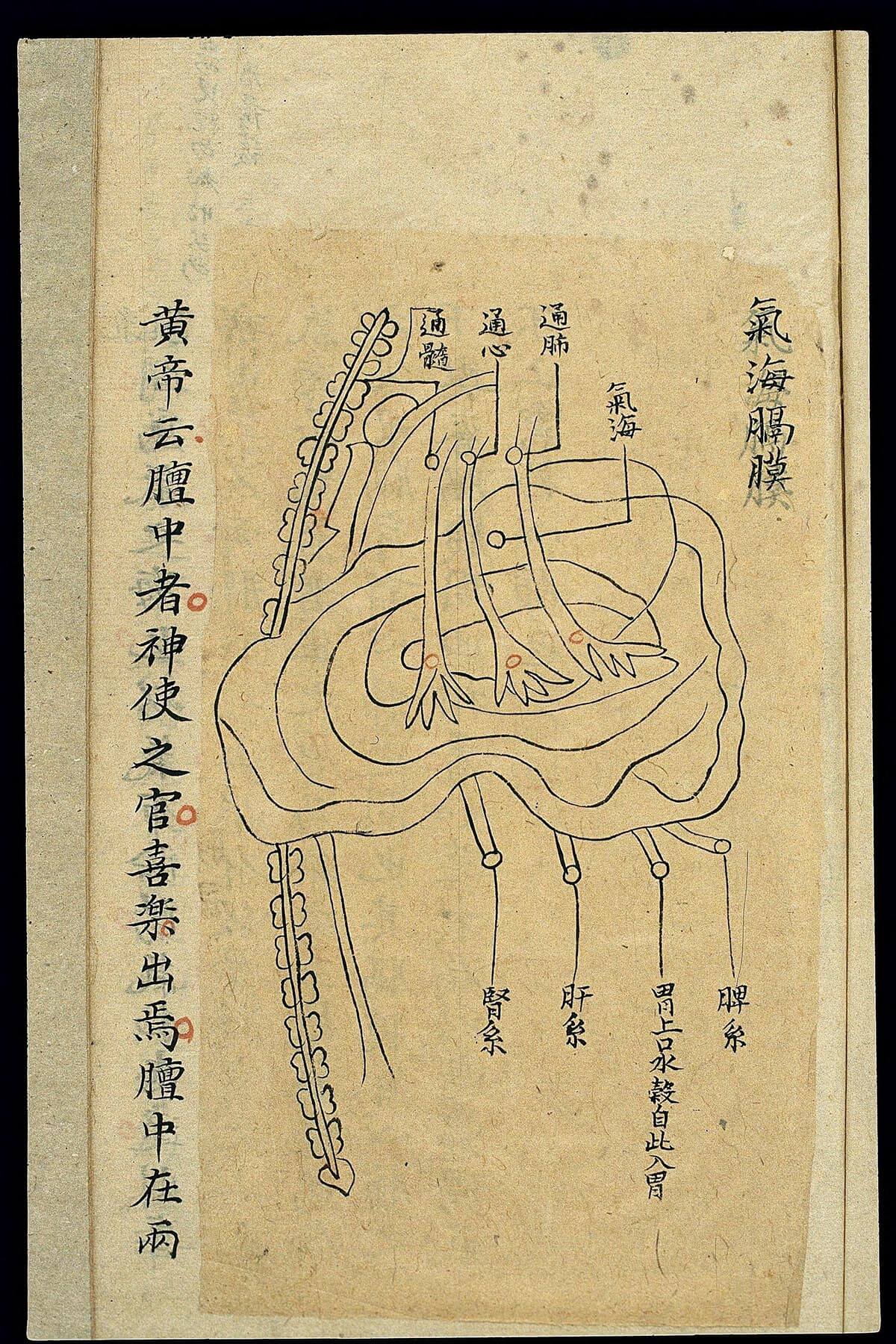

Li Jiong’s Neijing tu is preserved in the Ming Daoist canon woodblock print of 1436–49. It modelled bones, solid organs and the intestines alongside images of the bureaucrats, animal and other spirits that inhabited the body. These medical maps served as aids for self-cultivators practising breathing meditations and therapeutic movements. They were selectively adopted and adapted to new contexts as they travelled outside China.

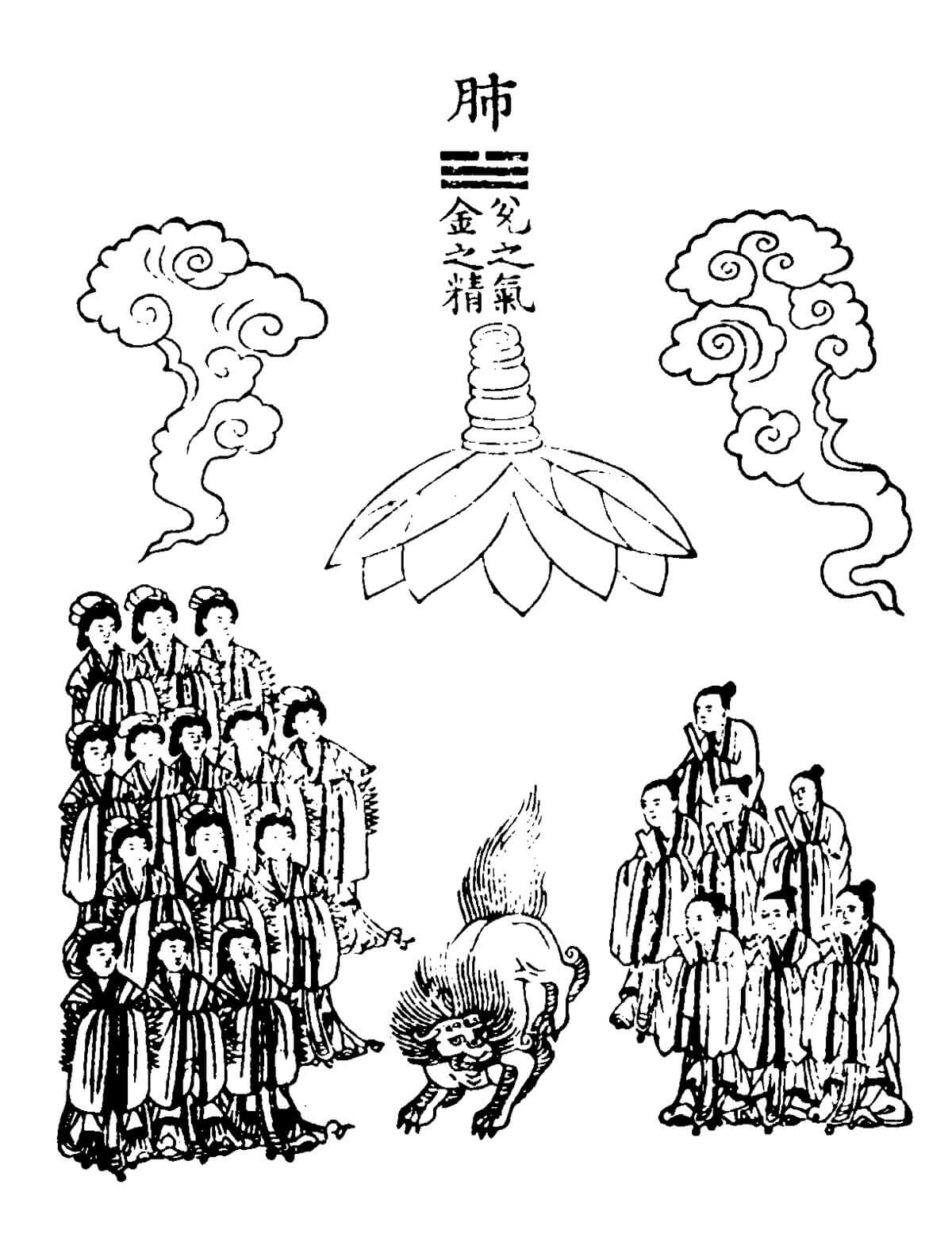

In Korea the alchemical traditions of spirit animals found traction in Kim Yemong et al.’s Ui’bang’ryuchui 醫方類聚 (Classified Collection of Medical Remedies) of 1477 CE for their attractive Daoist and alchemical vision of the internal landscape of the human body. Daoist healing techniques were associated with gentler forms of self-cultivation and therapy, and could convey the sensory and imaginative realms of what happened in the guts through the imagination of working on qi.

In contrast, in his late medieval scriptorium in Tabriz, the court physician and statesman, Rashīd al-Dīn (1274–1318), was fascinated by Li Jiong’s images of the organs and included them in his Tansūqnāma-i Īlkhan dar funūn-i ‘ulūm-i khatā’ Ī (The Treasure Book of the Ilkhan on Chinese Science and Techniques), dated AH 713 (1313); but, despite the positive Persian reception of images of the phoenix in the decorative arts, he was not interested in Chinese spirit animals that apparently resided in the body. Did the Chinese images he reproduced of the guts and other anatomical figures travel further west? According to an anonymous manuscript now in the Süleymaniye Library, a group of Byzantine doctors visited Rashīd al-Dīn in Tabriz. They asked him seven questions concerned with different aspects of human physiology, such as the blood and the spirit, and the factors that differentiate humans from animals. They were also interested in the nature of the senses, the animation of the body, the nails, and the hair. Their first question concerned the relationship between the blood and the spirit. Rashid al-Din’s response was that the fundamental principle of life was the motivating force of the spirit on the movement of the blood. This suggests that he probably did understand the Chinese concept of qi despite his translation of it as “blood.” Were the Byzantine doctors familiar with Rashid al-Din’s project and its anatomical images from China – two centuries before the innovations in anatomical illustration of Giacomo Berengario da Carpi and Vesalius in Europe?

Li Jiong’s Neijing tu is preserved in the Ming Daoist canon woodblock print of 1436–49. It modelled bones, solid organs and the intestines alongside images of the bureaucrats, animal and other spirits that inhabited the body. These medical maps served as aids for self-cultivators practising breathing meditations and therapeutic movements. They were selectively adopted and adapted to new contexts as they travelled outside China.

In Korea the alchemical traditions of spirit animals found traction in Kim Yemong et al.’s Ui’bang’ryuchui 醫方類聚 (Classified Collection of Medical Remedies) of 1477 CE for their attractive Daoist and alchemical vision of the internal landscape of the human body. Daoist healing techniques were associated with gentler forms of self-cultivation and therapy, and could convey the sensory and imaginative realms of what happened in the guts through the imagination of working on qi.

In contrast, in his late medieval scriptorium in Tabriz, the court physician and statesman, Rashīd al-Dīn (1274–1318), was fascinated by Li Jiong’s images of the organs and included them in his Tansūqnāma-i Īlkhan dar funūn-i ‘ulūm-i khatā’ Ī (The Treasure Book of the Ilkhan on Chinese Science and Techniques), dated AH 713 (1313); but, despite the positive Persian reception of images of the phoenix in the decorative arts, he was not interested in Chinese spirit animals that apparently resided in the body. Did the Chinese images he reproduced of the guts and other anatomical figures travel further west? According to an anonymous manuscript now in the Süleymaniye Library, a group of Byzantine doctors visited Rashīd al-Dīn in Tabriz. They asked him seven questions concerned with different aspects of human physiology, such as the blood and the spirit, and the factors that differentiate humans from animals. They were also interested in the nature of the senses, the animation of the body, the nails, and the hair. Their first question concerned the relationship between the blood and the spirit. Rashid al-Din’s response was that the fundamental principle of life was the motivating force of the spirit on the movement of the blood. This suggests that he probably did understand the Chinese concept of qi despite his translation of it as “blood.” Were the Byzantine doctors familiar with Rashid al-Din’s project and its anatomical images from China – two centuries before the innovations in anatomical illustration of Giacomo Berengario da Carpi and Vesalius in Europe?

GUTS IN CHINESE TRADITIONS

It is only lately that we are beginning to see studies that go beyond essentialising the anatomical traditions of China and ‘the West’, with the practices of modernity associated with the latter concept. Since the invention of printing in late medieval China there have been many illustrated medical books in black and white which have displayed traditions of visualising the guts. A reflection on the epistemological role of images in China and their afterlives helps us counter those established historiographical discourses associated with hierarchies of modernity and civilisation.

Recurring images based on the dissection of dead bodies travelled east and westwards, crossing medical, religious and social boundaries. It is tempting to attribute to them universal and constant meanings that transcend their original or local circumstances of production, rather than to focus on the virtue inherent in their translatability, their plasticity of signification. Do we really need to talk about authenticity, when it is clear that there were many points of innovation in the history of, for example, the Chart of the Inner Landscape of 1269 itself? It images a combination of early Chinese state-sponsored dissection carried out over 1000 years previously and Daoist visualisations of the spirits that lived in the body; and is re-represented according to changing textual and visual authorities that we see in the late medieval Persian and Korean adaptations of the knowledge it displays. The guts of Li Jiong’s images represent the Middle and Lower Cinnabar Fields of inner alchemy. Altogether there were three Cinnabar Fields located in the areas of the forehead (Upper Cinnabar Field), around the heart (Middle Cinnabar Field) and abdomen (Lower Cinnabar Field). These were key to the breathing, meditation, and visualisations of internal practices. These inner spaces mirrored a Daoist pantheon and cosmological divisions, yet do not appear to contradict an anatomical vision of the organs and guts since they were printed together. We also see the spine, the kidneys and various connecting vessels alongside the spirits that lived in the guts: the red infant who represented the pursuit of immortality, two of the cosmological animals, the green dragon and the white tiger as well as the Qi Lun 臍輪 (navel cakra). It seems that Indian ideas have seamlessly translated into a Daoist chart. These visualisations of the guts achieve a kind of transcendental quality as they are adapted to new circumstances, old images participating in the creation of new forms of knowledge-making as they travel through time and space.

Recurring images based on the dissection of dead bodies travelled east and westwards, crossing medical, religious and social boundaries. It is tempting to attribute to them universal and constant meanings that transcend their original or local circumstances of production, rather than to focus on the virtue inherent in their translatability, their plasticity of signification. Do we really need to talk about authenticity, when it is clear that there were many points of innovation in the history of, for example, the Chart of the Inner Landscape of 1269 itself? It images a combination of early Chinese state-sponsored dissection carried out over 1000 years previously and Daoist visualisations of the spirits that lived in the body; and is re-represented according to changing textual and visual authorities that we see in the late medieval Persian and Korean adaptations of the knowledge it displays. The guts of Li Jiong’s images represent the Middle and Lower Cinnabar Fields of inner alchemy. Altogether there were three Cinnabar Fields located in the areas of the forehead (Upper Cinnabar Field), around the heart (Middle Cinnabar Field) and abdomen (Lower Cinnabar Field). These were key to the breathing, meditation, and visualisations of internal practices. These inner spaces mirrored a Daoist pantheon and cosmological divisions, yet do not appear to contradict an anatomical vision of the organs and guts since they were printed together. We also see the spine, the kidneys and various connecting vessels alongside the spirits that lived in the guts: the red infant who represented the pursuit of immortality, two of the cosmological animals, the green dragon and the white tiger as well as the Qi Lun 臍輪 (navel cakra). It seems that Indian ideas have seamlessly translated into a Daoist chart. These visualisations of the guts achieve a kind of transcendental quality as they are adapted to new circumstances, old images participating in the creation of new forms of knowledge-making as they travel through time and space.

References

Akasoy, A., C. Burnett and R. Yoeli-Tlalim (eds) 2013, Rashid al-Din as an Agent and Mediator of Cultural Exchanges in Ilkhanid Iran, London: Warburg Institute.

Berlekamp, P., V. Lo and Wang Yidan 王一丹 2015, ‘Administering art, history, and science in the Mongol empire’, in Landau (ed.), 53–85.

Lo, V and P, Barrett (eds) 2018, Imagining Chinese Medicine, Leiden: Brill.

Lo, V, Introduction, 2018 in Lo and Barrett (eds), 1-28.

Lo, V and Wang Yidan 王一丹 2013, ‘Blood or Qi circulation? On the nature of authority in Rashīd al-Dīn’s Tānksūqnāma (The Treasure Book of Ilqān on Chinese Science and Techniques)’, in Akasoy, Burnett and Yoeli-Tlalim (eds), 127–72.

Lo, V and Wang Yidan 王一丹2018, ‘Chasing the Vermilion Bird: Late Medieval Alchemical Transformations in The Treasure Book of Ilkhan on Chinese Science and Techniques’ in Lo and Barrett (eds), 291-304.

Shin Dongwon 신동원 2018, ‘Korean Anatomical Charts in the Context of the East Asian Medical Tradition’ in Lo and Barrett (eds), 327-338.

Zhang Qicheng 張其成 2018, ‘Embodying animal spirits in the vital organs: Daoist alchemy in Chinese medicine’, in Lo and Barrett (eds), 389-396.

Berlekamp, P., V. Lo and Wang Yidan 王一丹 2015, ‘Administering art, history, and science in the Mongol empire’, in Landau (ed.), 53–85.

Lo, V and P, Barrett (eds) 2018, Imagining Chinese Medicine, Leiden: Brill.

Lo, V, Introduction, 2018 in Lo and Barrett (eds), 1-28.

Lo, V and Wang Yidan 王一丹 2013, ‘Blood or Qi circulation? On the nature of authority in Rashīd al-Dīn’s Tānksūqnāma (The Treasure Book of Ilqān on Chinese Science and Techniques)’, in Akasoy, Burnett and Yoeli-Tlalim (eds), 127–72.

Lo, V and Wang Yidan 王一丹2018, ‘Chasing the Vermilion Bird: Late Medieval Alchemical Transformations in The Treasure Book of Ilkhan on Chinese Science and Techniques’ in Lo and Barrett (eds), 291-304.

Shin Dongwon 신동원 2018, ‘Korean Anatomical Charts in the Context of the East Asian Medical Tradition’ in Lo and Barrett (eds), 327-338.

Zhang Qicheng 張其成 2018, ‘Embodying animal spirits in the vital organs: Daoist alchemy in Chinese medicine’, in Lo and Barrett (eds), 389-396.

![SET 2a+b Huangting dunjia yuanshen jing (Buch der verborgenen Periode und der kausale [Karma] Körper des gelben Hofes) Die beiden Schwarz-Weiß-Bilder aus dem 15. Jahrhundert zeigen unter einem Text in chinesischen Schriftzeichen vogelähnliche Wesen. Auf dem mit „A“ gekennzeichneten hochformatigen Bild links nimmt die Darstellung des Wesens die unteren zwei Drittel ein. Das Wesen ist schreitend mit angelegten Flügeln im Profil dargestellt. Es hat lange, dünne und unbefiederte Füße mit Krallen. Die Unterseite des schlanken kleinen Körpers ist hell. Das Deckgefieder ist gebändert. Lange Schwanzfedern, die in ihrer Form an die eines Pfaus erinnern, ragen aus dem Hinterleib. Der Hals ist nach hinten gebogen, seine kurzen Federn biegen sich nach oben, ebenso das Gefieder am Hinterkopf. Der dunkle Schnabel des Vogelwesens ist kurz und spitz mit einem Höcker darüber. Auf dem Kopf sitzt eine Federkrone Über dem Vogelwesen befinden sich neun, etwa gleich lange Spalten mit Schriftzeichen. Sie erstrecken sich über die gesamte Breite des Bildes. In einer Art Titelzeile darüber befinden sich mit einem größeren Abstand zu einander drei einzelne Schriftzeichen. Das rechts daneben positionierte Hochformat ist mit dem Buchstaben „B“ bezeichnet. Die Aufteilung des Bildraumes zwischen Schriftzeichen und Illustration ist ähnlich wie bei Bild „A“. Unter einer Art Überschrift aus zwei einzelnen Schriftzeichen erstrecken sich die neun Spalten über die gesamte Breite. Auch in diesem Bild ist das Vogelwesen mit angelegten Flügeln im Profil gezeichnet. Es steht auf einem Bein, das andere hat es angehoben und die Krallen zusammengezogen. Die Füße sind unbefiedert. Der helle Brust- und Bauchbereich ist durch eine klare Linie markiert. An den kleinen gedrungenen Körper schließt ein buschig befiederter emporgereckter Hals an. Das Wesen hält seinen drachenähnlichen Kopf in Richtung seines Rückens gedreht. Federbüschel ragen zu beiden Seiten seines Hauptes wie Ohren in die Höhe. Daneben treten zwei dünne gewellte Hörner hervor, ein weiteres Horn sitzt auf der Schnauze. Das Vogelwesen hat lange dünne Schwanzfedern, die an die eines Fasans erinnern. Sie sind schräg nach oben gerichtet. — — SET 2a+b Huangting dunjia yuanshen jing (Book of the Hidden Period and the Causal [Karma] Body of the Yellow Court) The two black and white images from the 15th century show bird-like creatures under a text in Chinese characters. In the portrait format image marked "A" on the left, the depiction of the creature occupies the lower two-thirds. The creature is shown in profile, striding with its wings spread. It has long, thin, and featherless feet with claws. The underside of its slender and small body is pale. The cover plumage is banded. Long tail feathers, resembling those of a peacock in shape, protrude from the abdomen. The neck is bent backwards, and its short feathers curve upwards, as does the plumage on the back of the head. The bird's dark beak is short and pointed with a hump above it. A crown of feathers sits on top of the head. Above the bird-like creature are nine columns of characters of roughly equal length. They extend across the entire width of the image. In a kind of title line at the top of the page, there are three individual characters at a greater distance from each other. On the portrait format image marked “B” on the right, the division of the pictorial space between the characters and the illustration is similar to that in image "A". Under a kind of heading consisting of two individual characters, the nine columns extend across the entire width. In this image, too, the bird is drawn in profile with its wings spread. It is standing on one leg, the other raised and the claws drawn together. The feet are not feathered. The light breast and belly area is marked by a clear line. The small stocky body is joined by a bushy, feathered upturned neck. The creature holds its dragon-like head turned towards its back. Tufts of feathers rise up on either side of its head like ears. Two thin wavy horns protrude next to it, another horn sits on its snout. The creature has long thin tail feathers that resemble those of a pheasant. They are slanted upwards.](https://comparative-guts.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2a-copy.jpg)