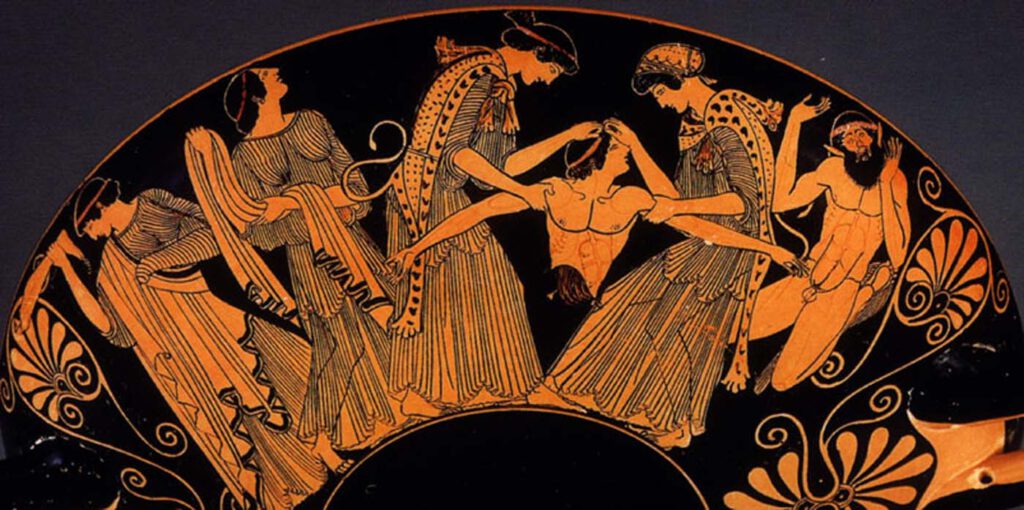

Athenian red-figure cup attributed to Douris

Athenian red-figure cup attributed to Douris death of Pentheus (detail), c.480 B.C. Cervetri, Museo Nazionale CeritePhoto: 2023@photo Scala, Florence, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas /Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence – The death of Pentheus is most familiar in the description given by Euripides in Bacchae. There a messenger speech describes how Pentheus’ mother, Agave, and […]

A female ‘open torso’ figurine

A female ‘open torso’ figurine Nottingham Castle Museum – This female figurine was discovered at the sanctuary of the Graeco-Roman goddess Artemis/Diana Nemorensis at Lake Nemi in Italy in 1885. It was excavated and recovered from a sacred pit where it had been ritually disposed of sometime in antiquity after it had ceased to be […]

A polyvisceral plaque

A polyvisceral plaque Museo Nazionale Etrusco Di Villa Giulia – This Etruscan polyvisceral plaque from Tessennano in Latium in Italy is thought to date from around 400 BCE. Anatomical votives like these were deposited in sanctuaries and temples as offerings to the gods, generally interpreted as a gesture of gratitude for some manner of divine […]

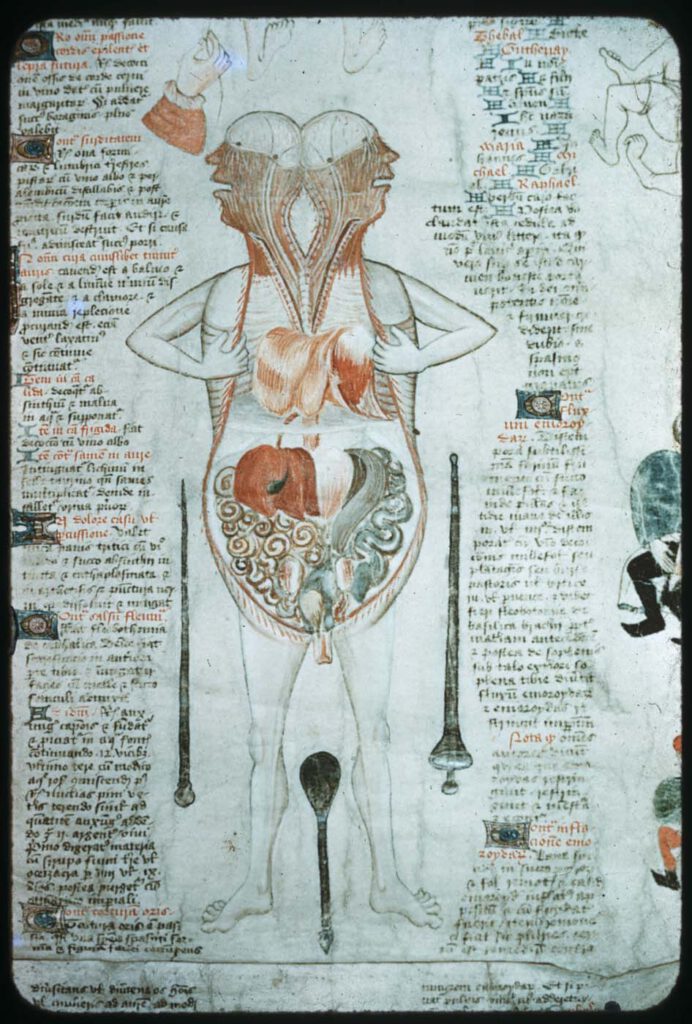

Illustration accompanying De Arte Physicali et de Cirurgia

Illustration accompanying De Arte Physicali et de Cirurgia, attributed to John Arderne Stockholm, Kungliga Biblioteket X.118, fol. 6v/6r; c. 1430 – While the frontal approach to anatomical illustration exhibited in the Five/Nine-Figure Series and Guido da Vigevano’s work is most dominant, an alternative, sagittal approach emerged in the medieval period and survives in a few […]

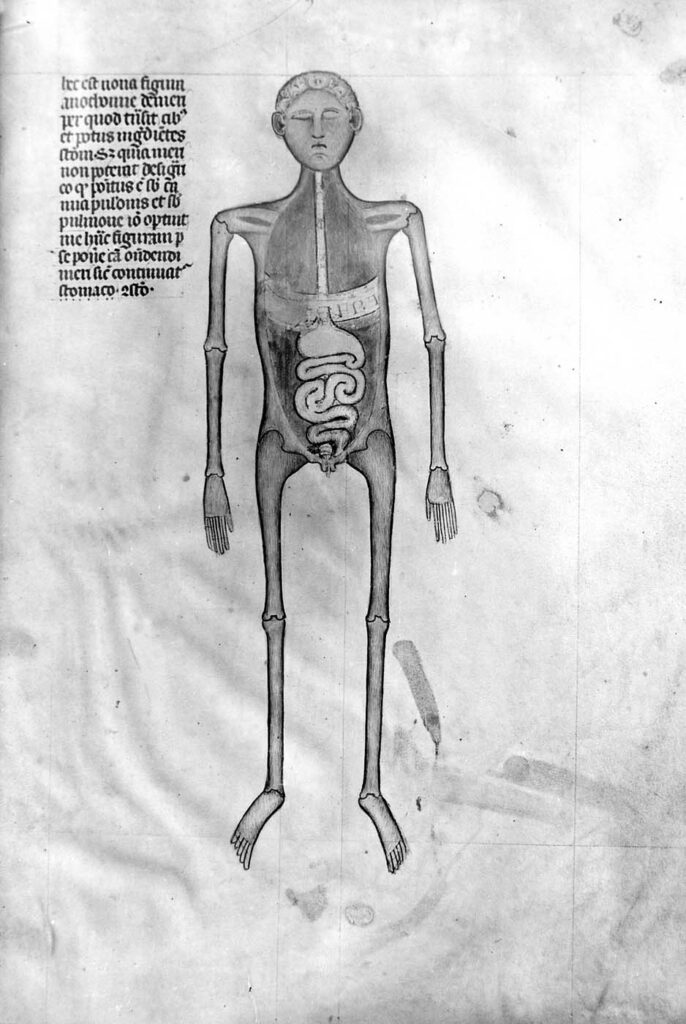

Guido da Vigevano’s Anathomia, Figure 8

Guido da Vigevano’s Anathomia, Figure 9 (1345) Guido da Vigevano, Anathomia, 1345CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 – Although human dissection began to be systematically practiced in Italy in the early 14th century, it was not immediately embraced across Europe. This prompted Guido da Vigevano to produce a series of seventeen illustrations included in his Book of Notable […]