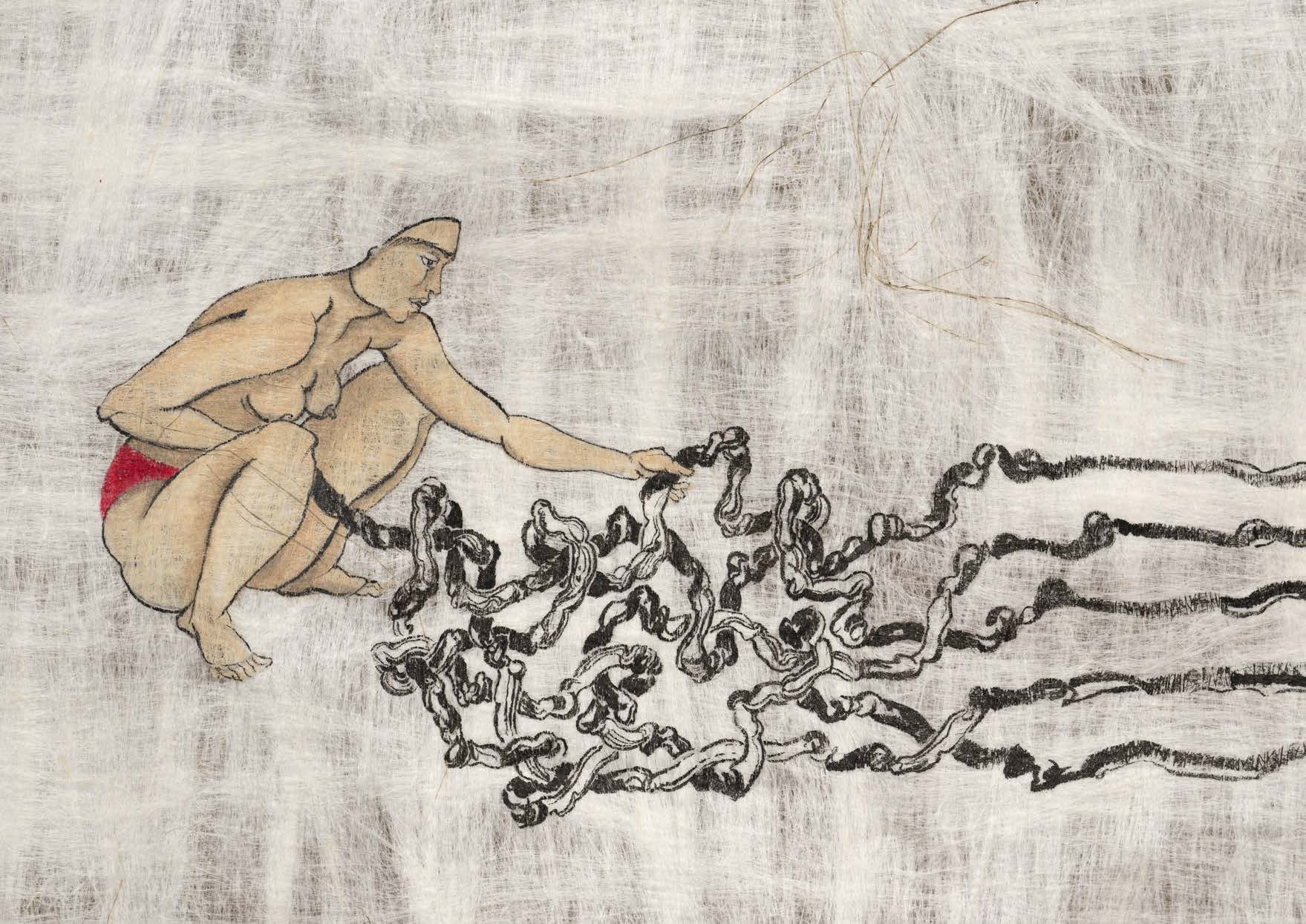

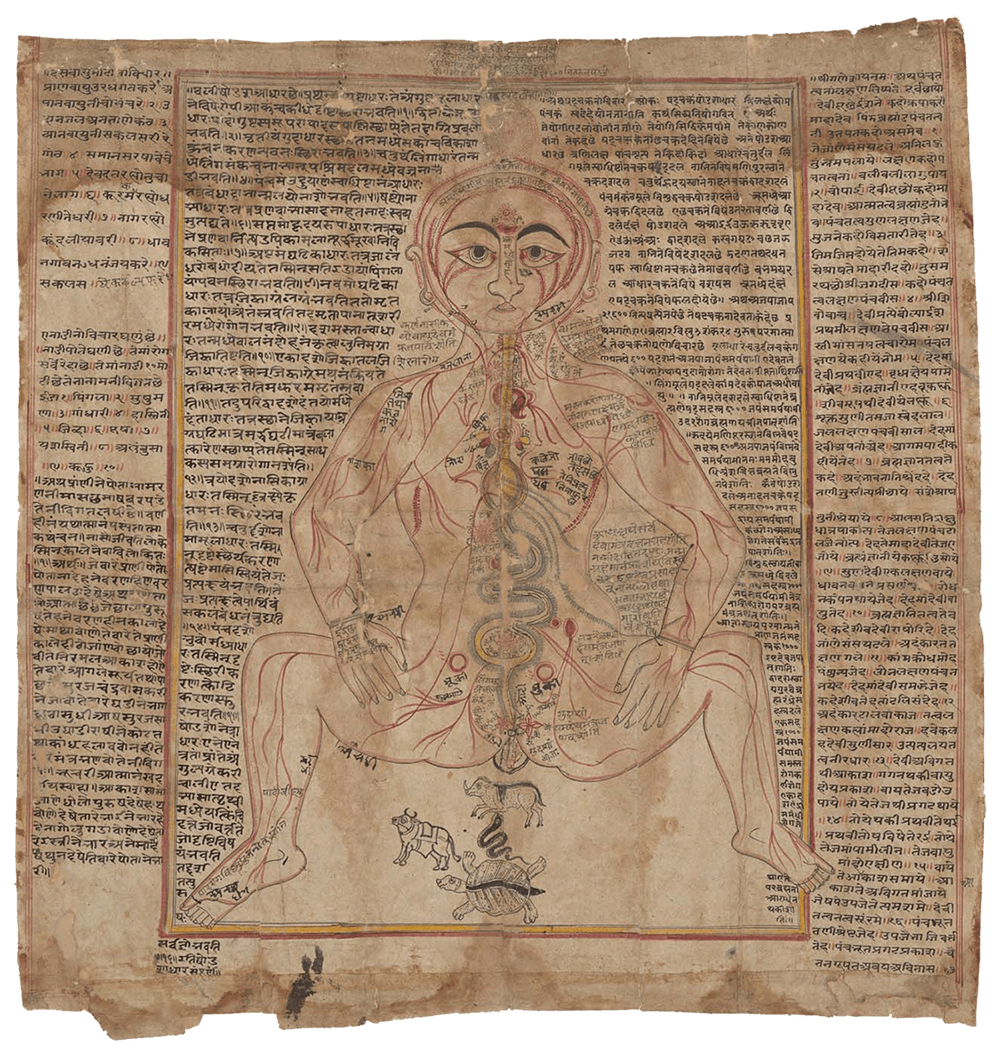

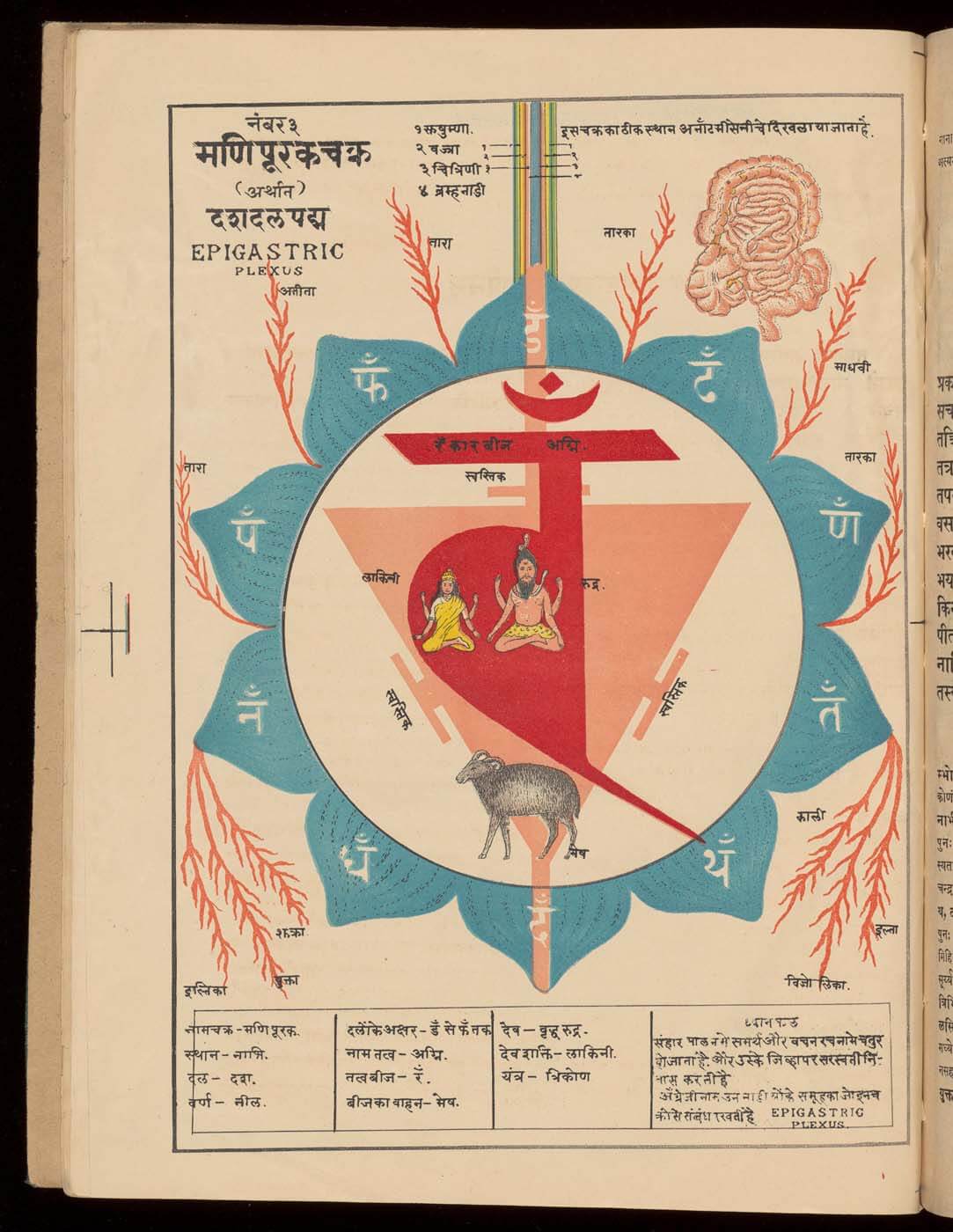

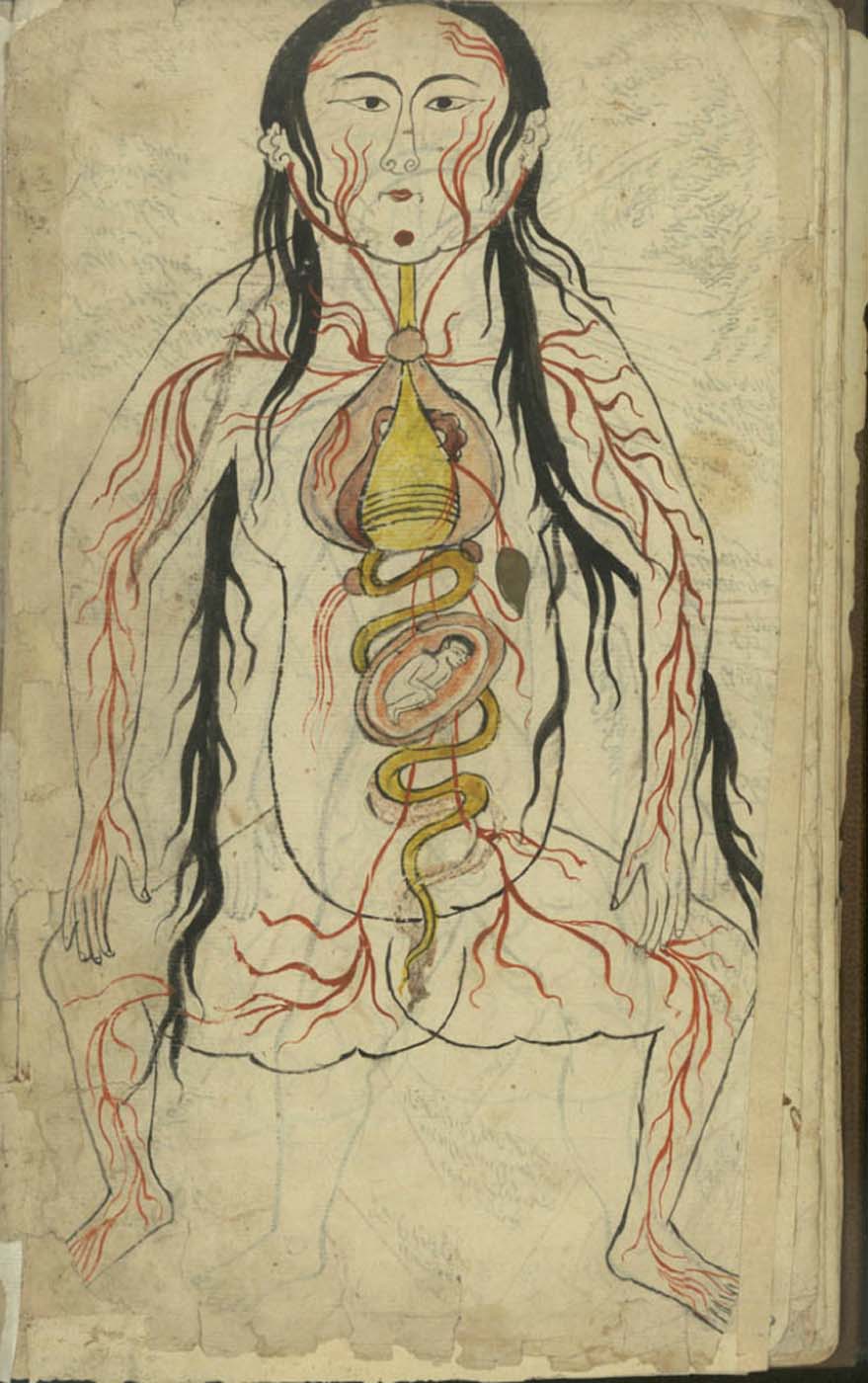

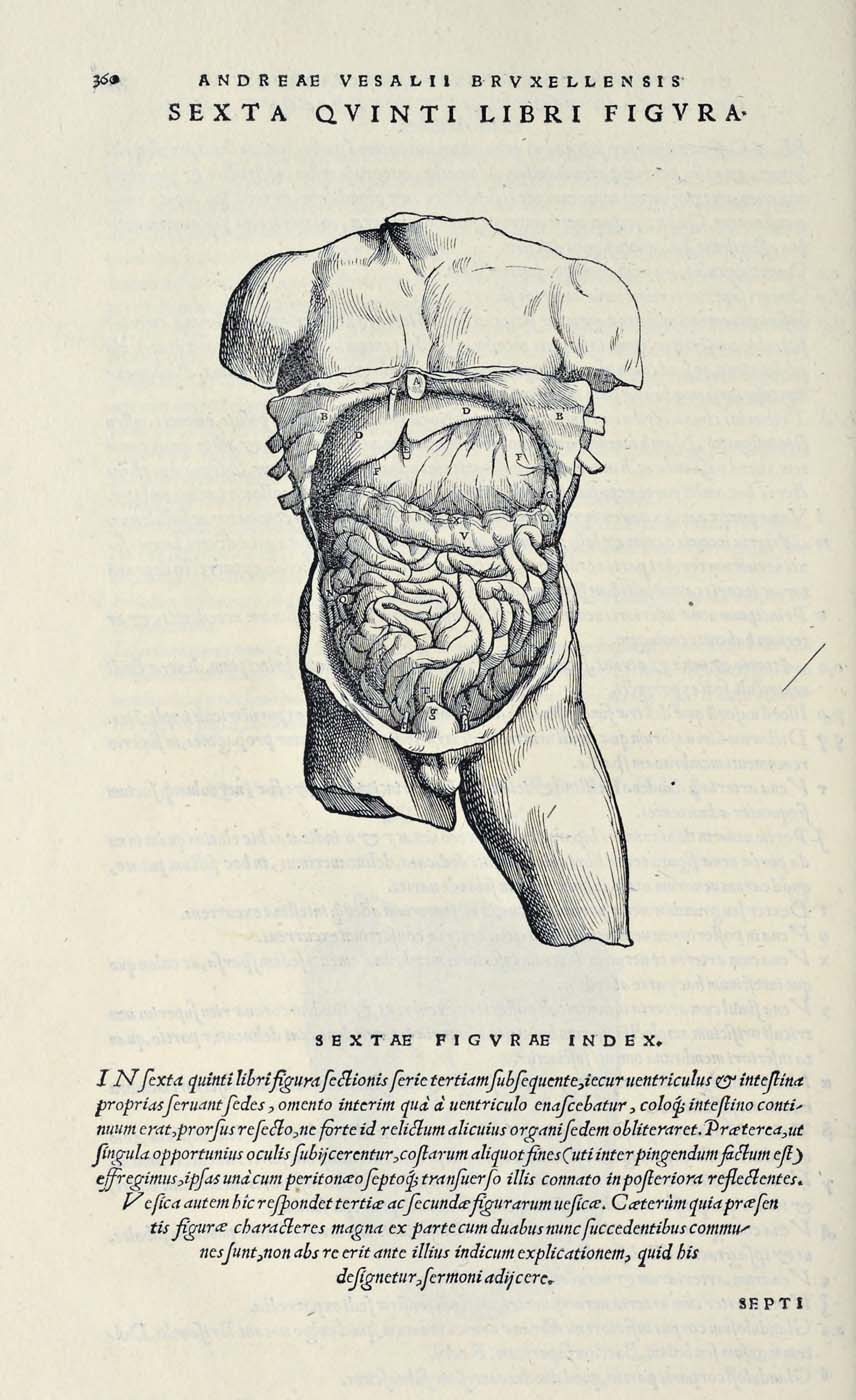

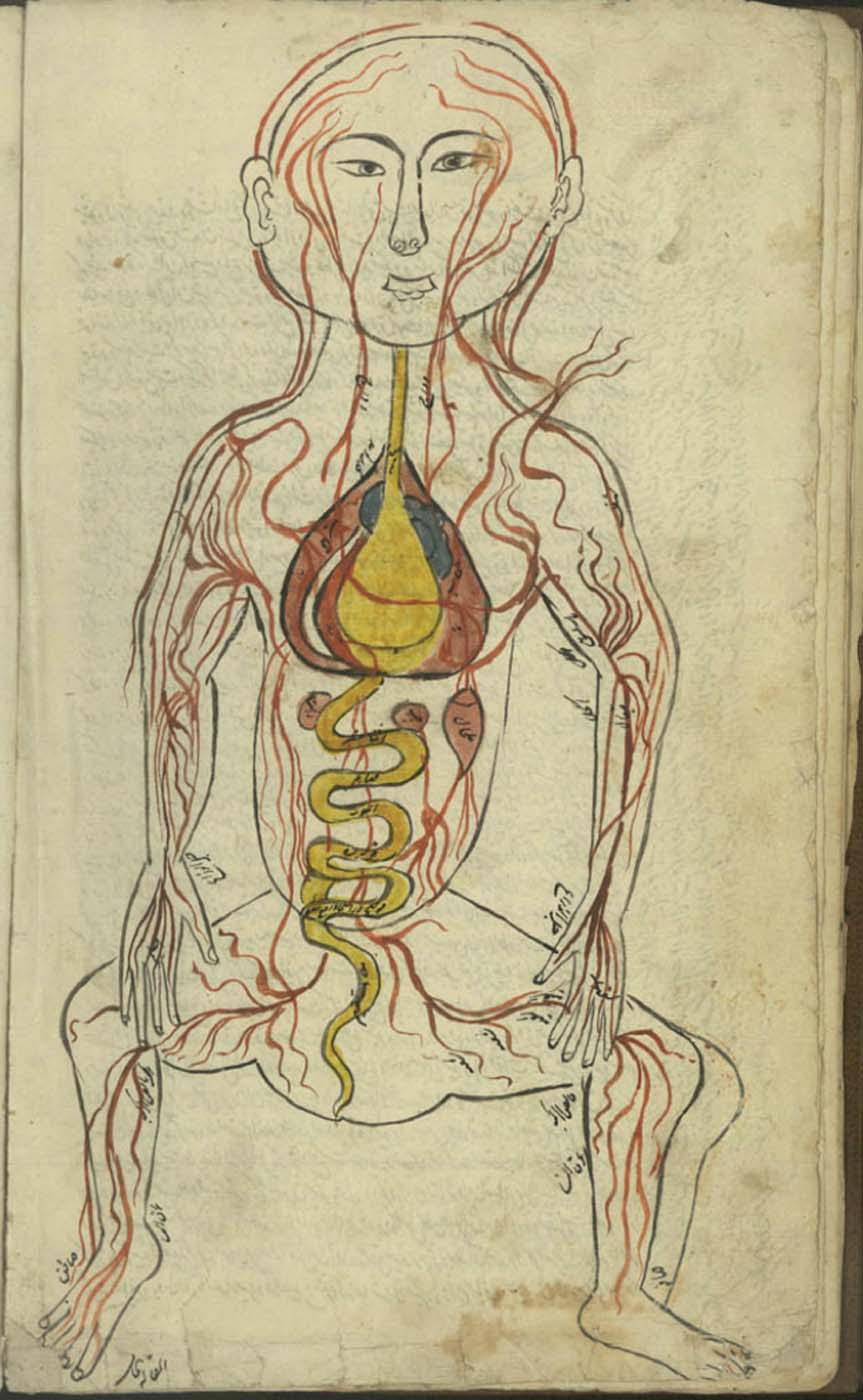

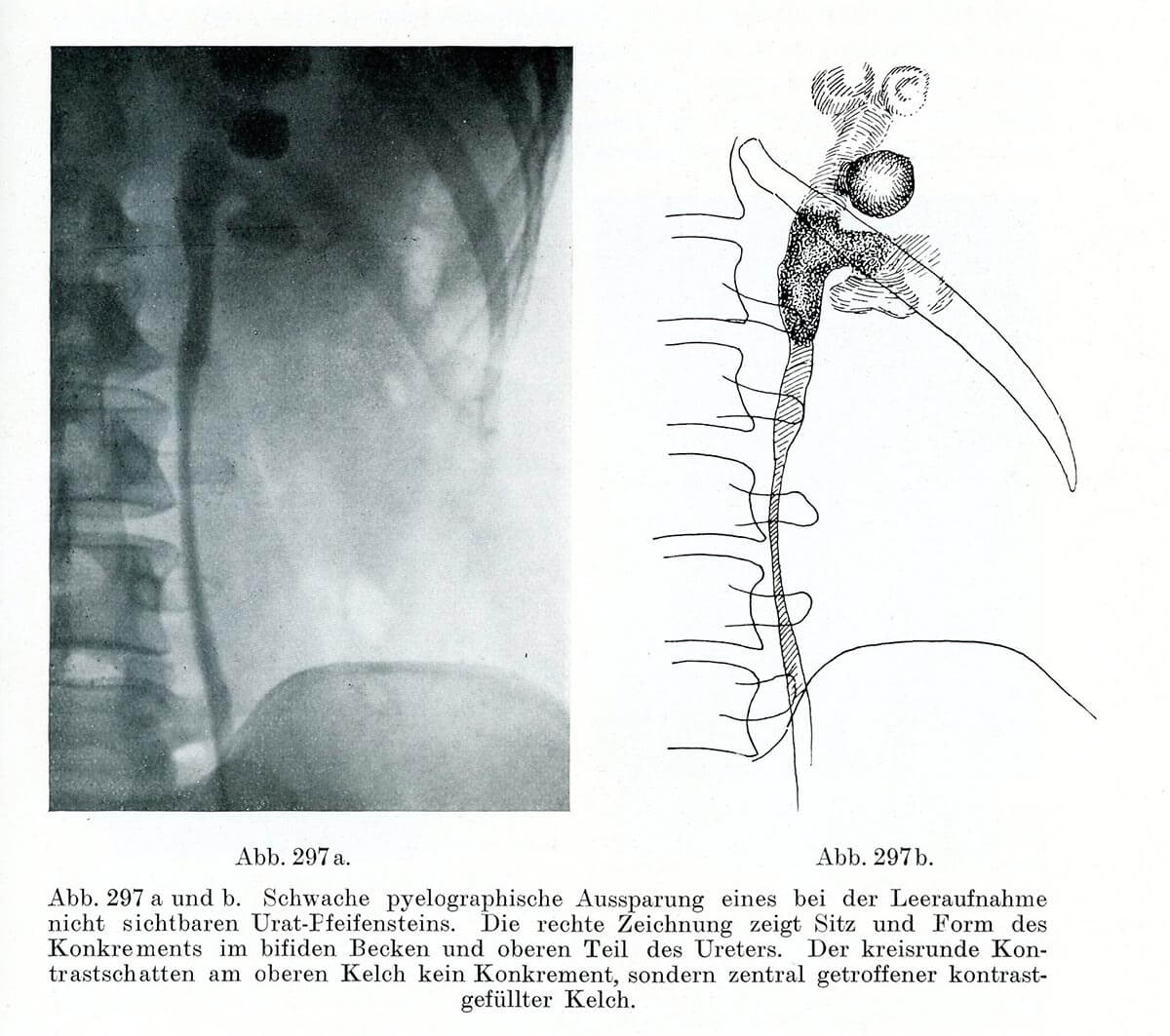

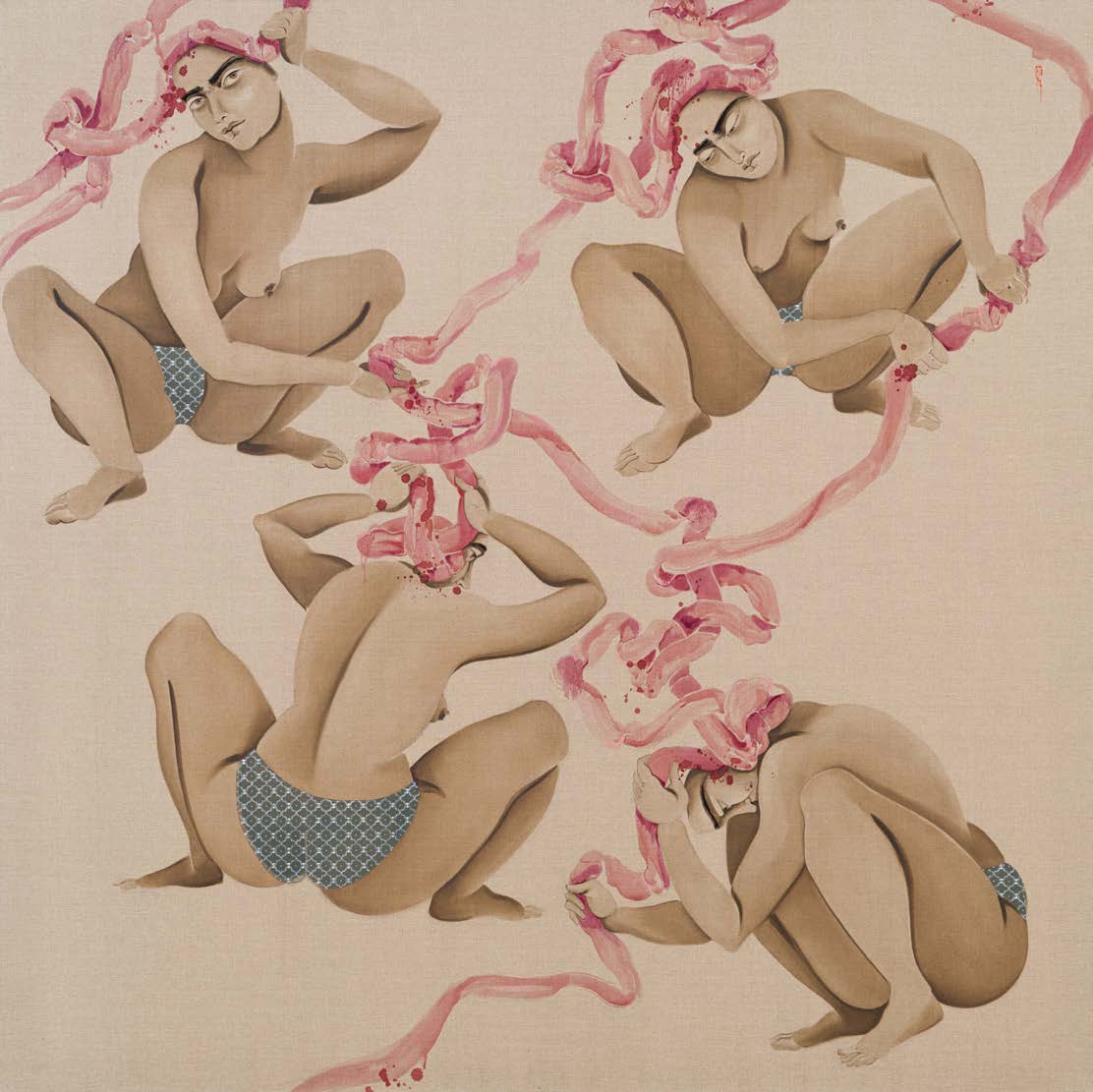

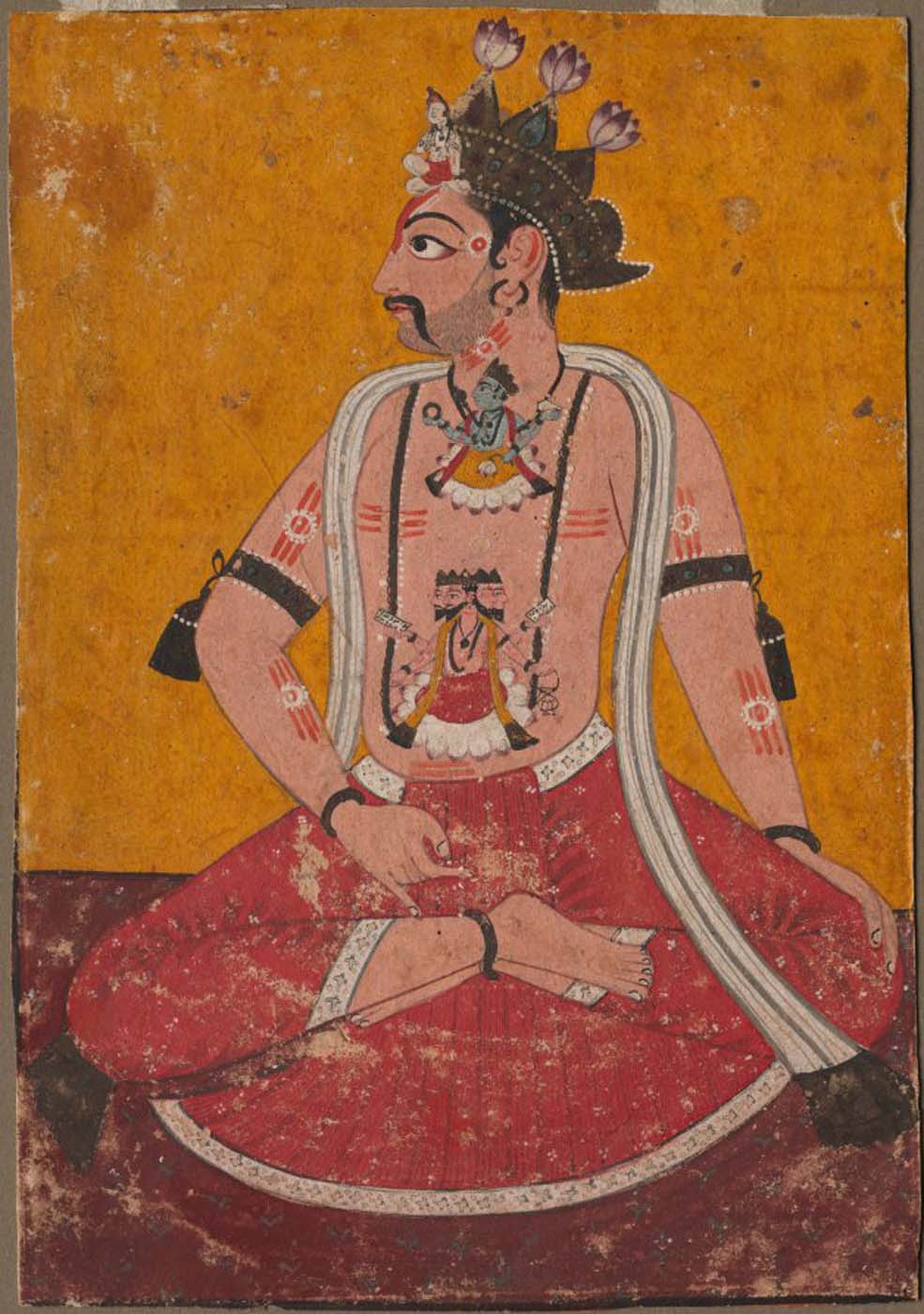

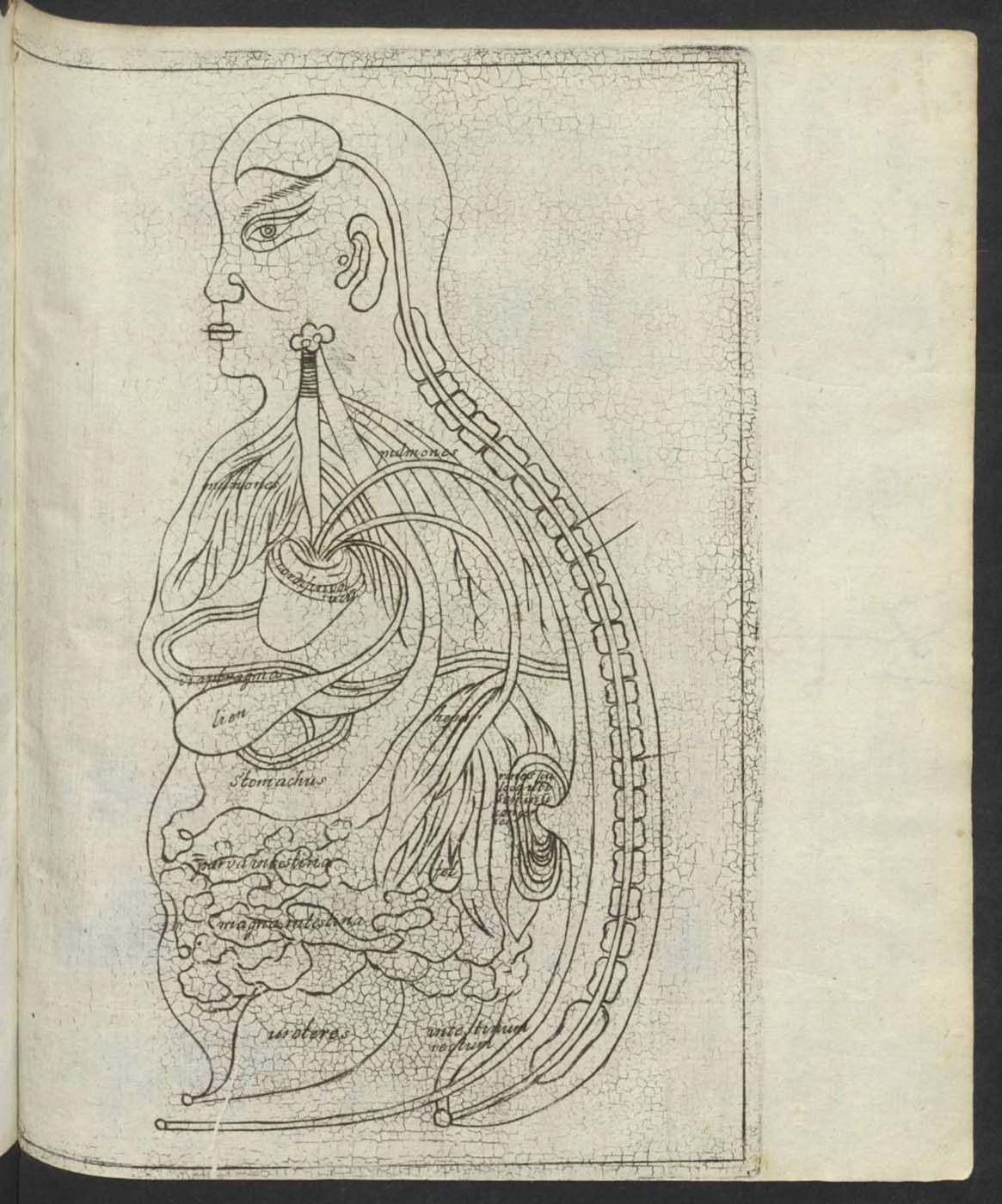

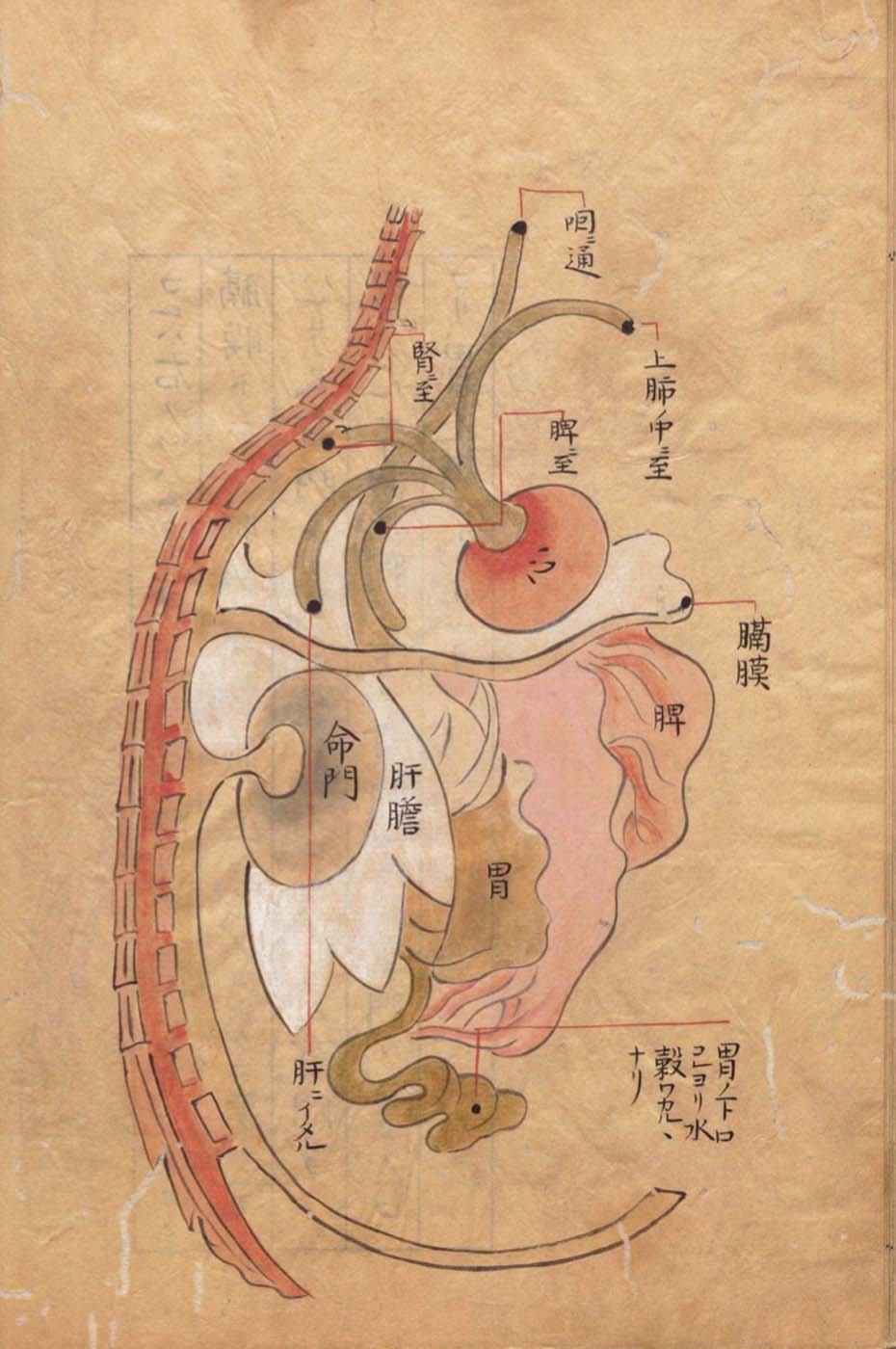

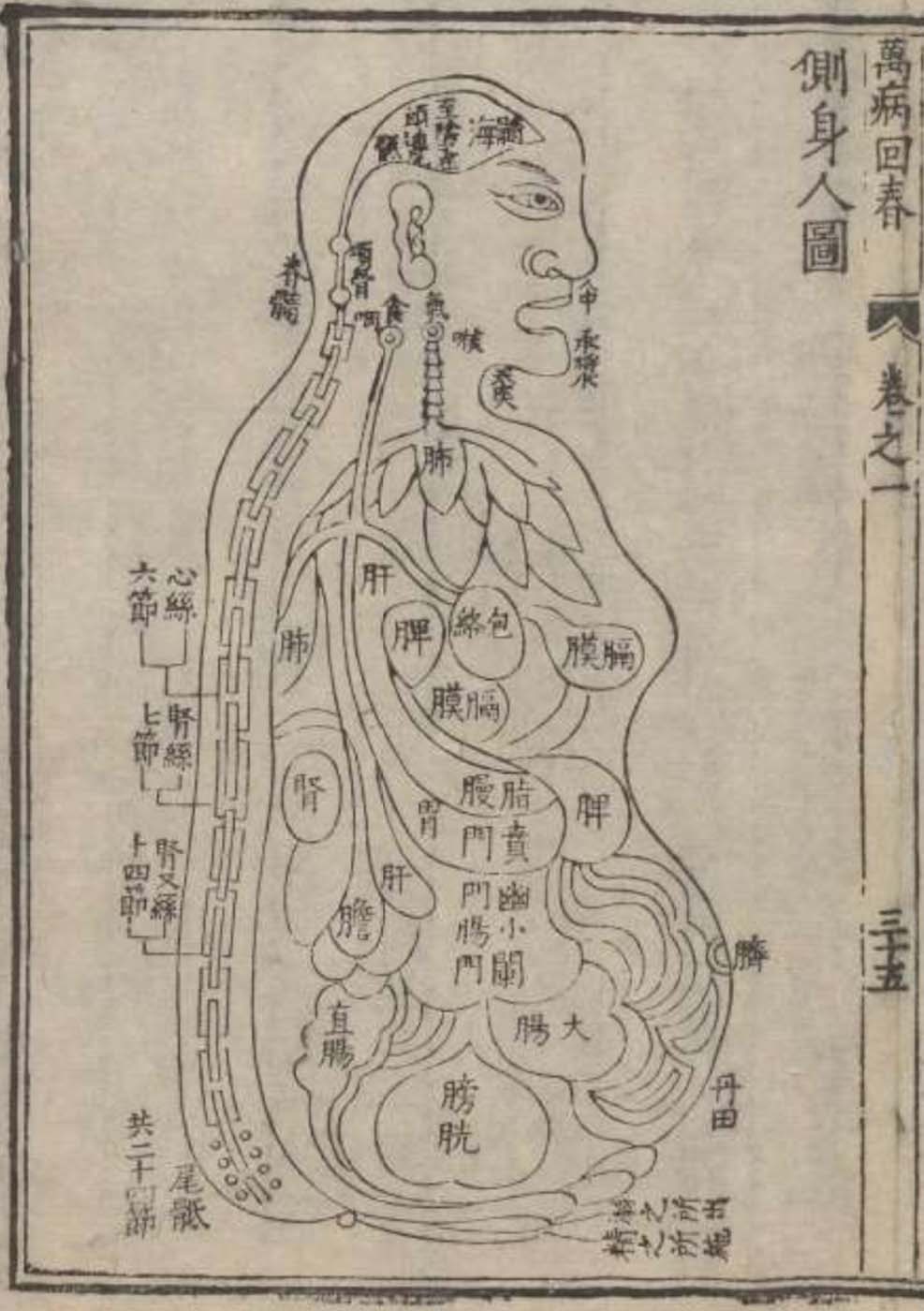

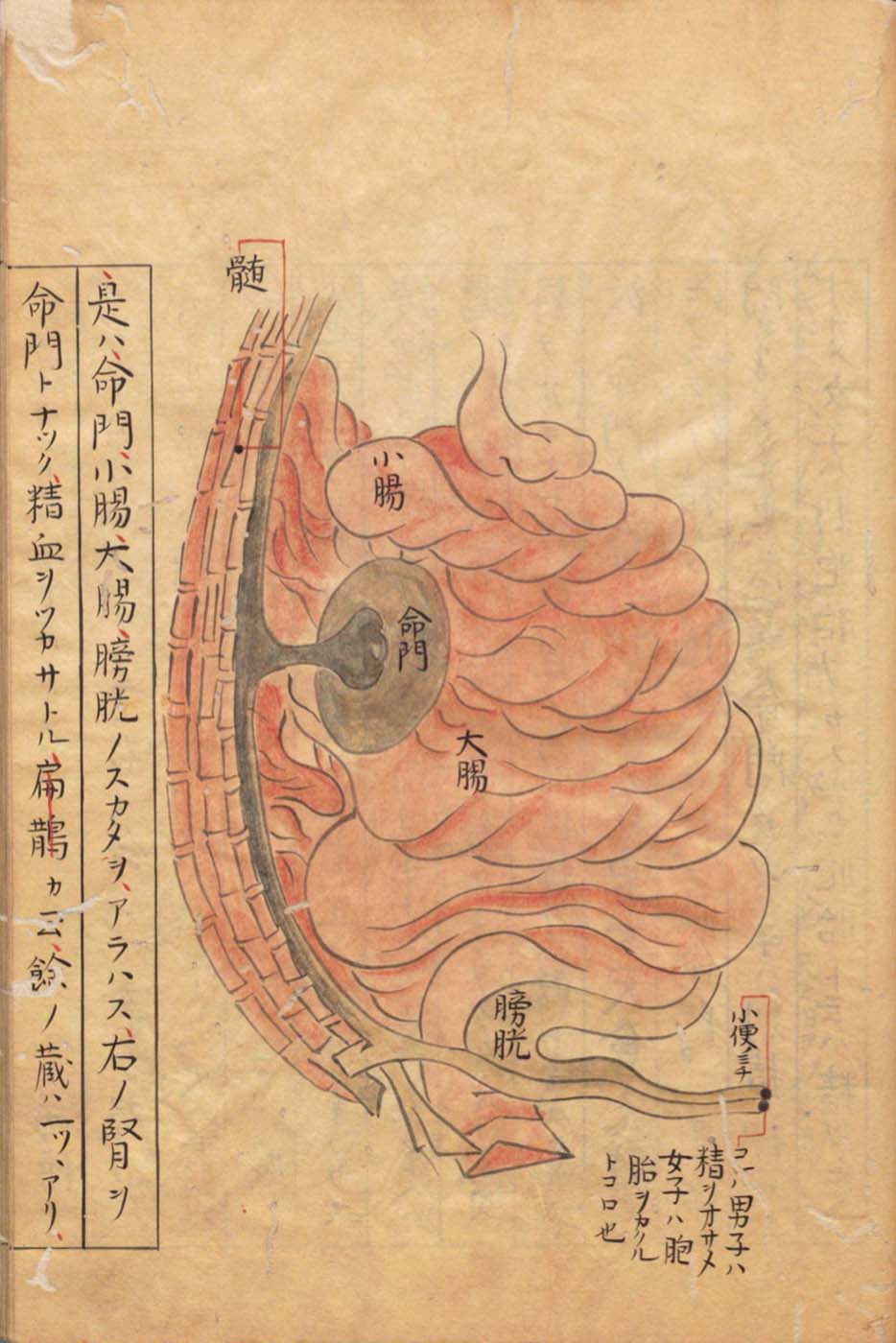

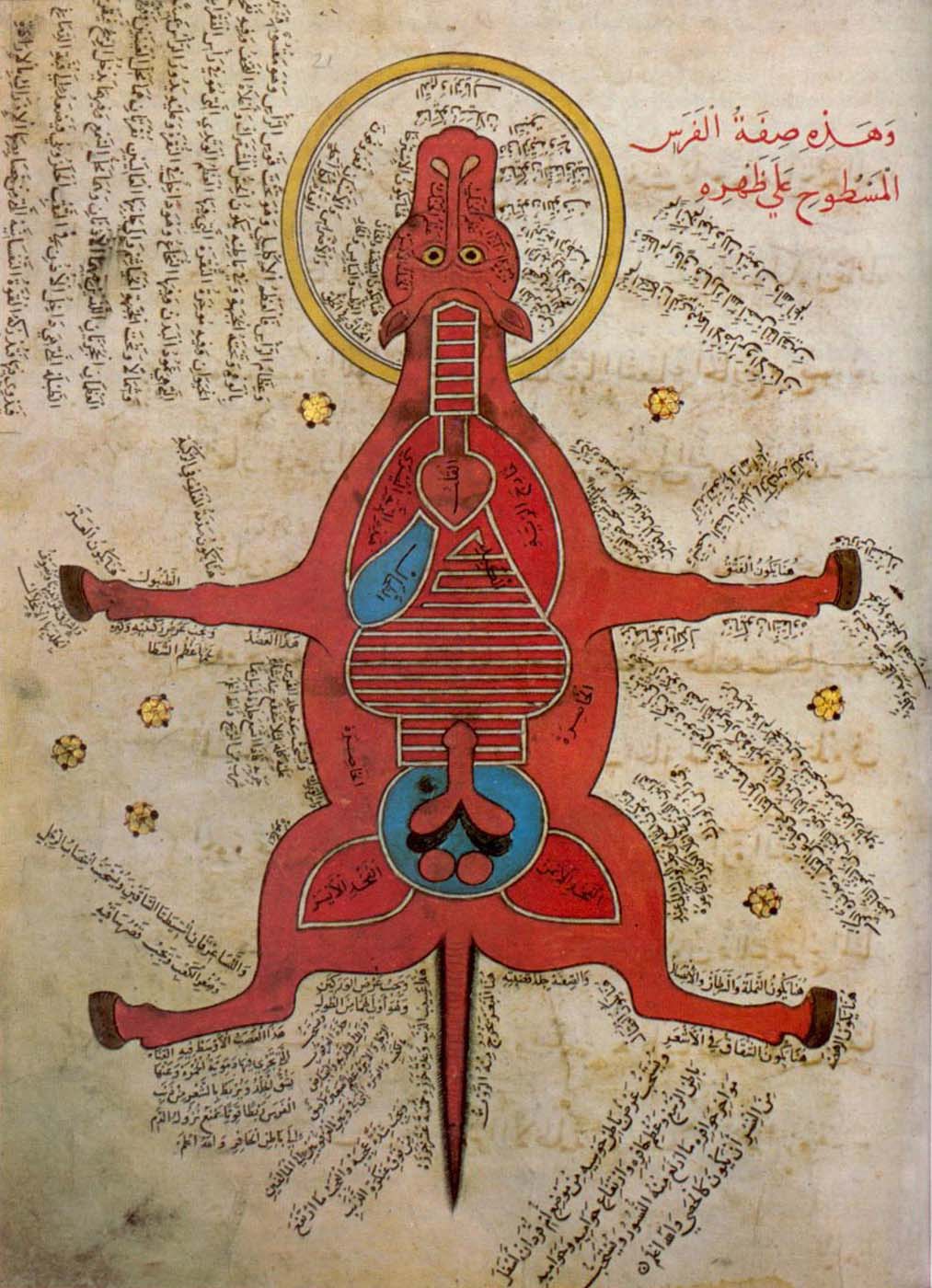

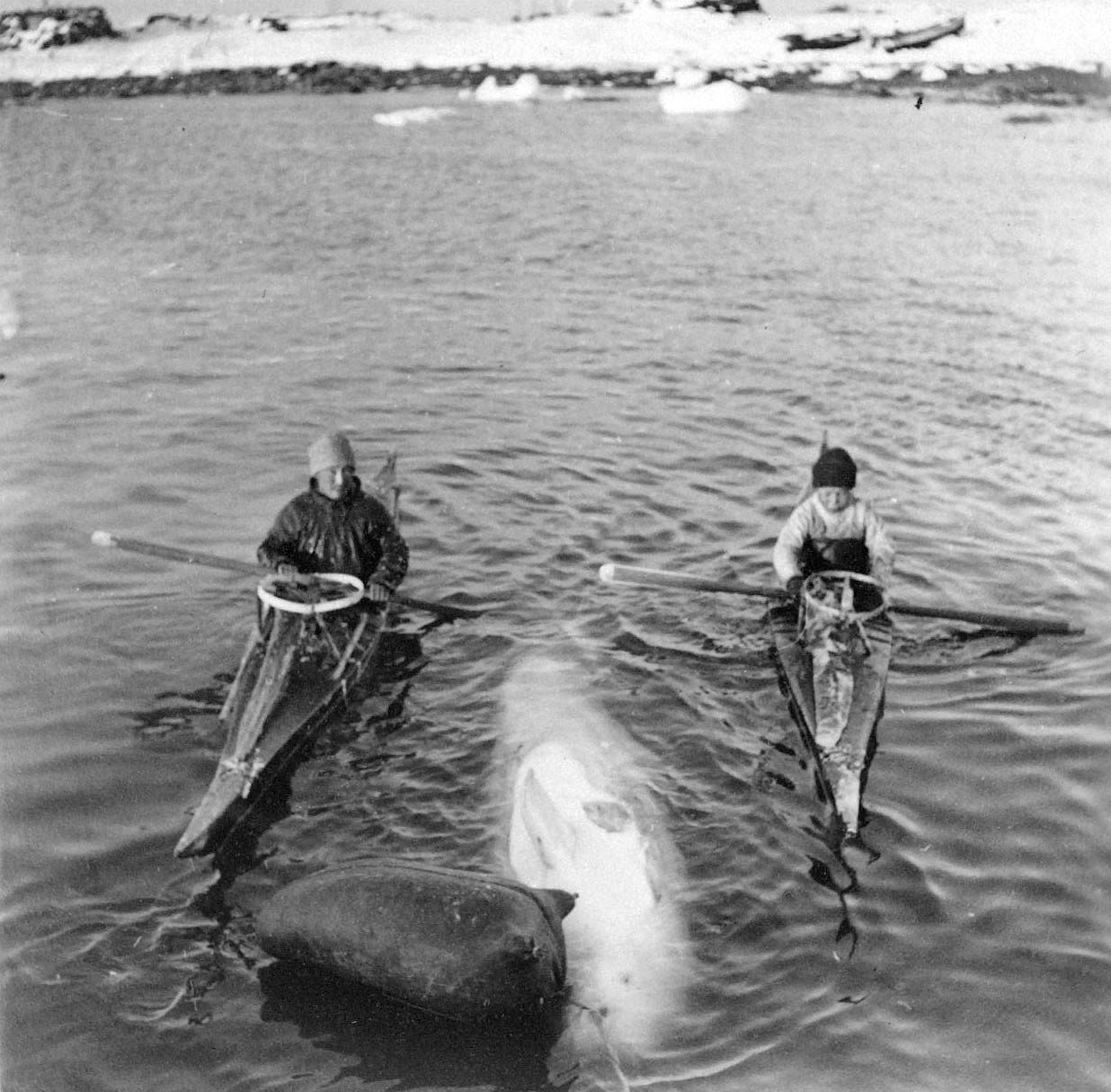

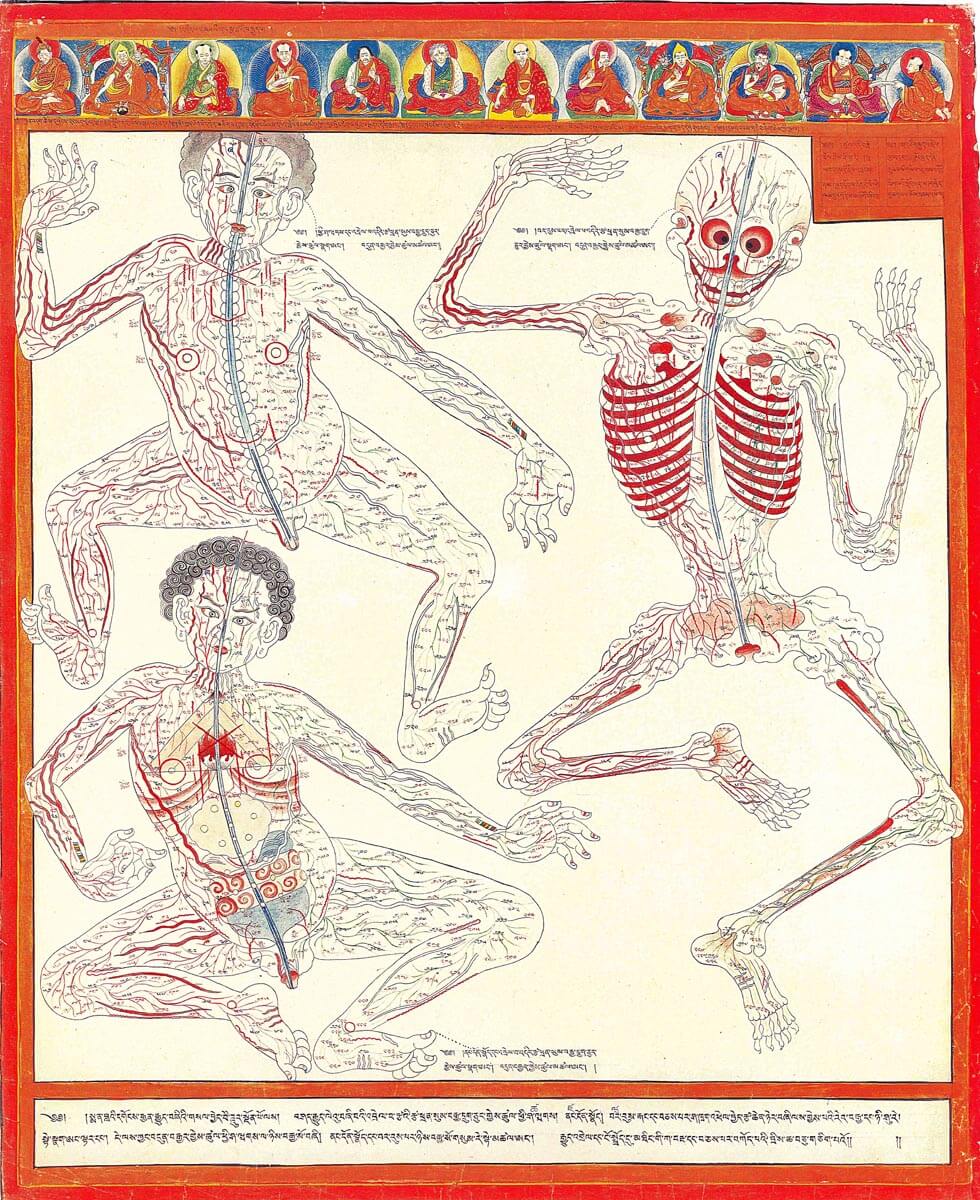

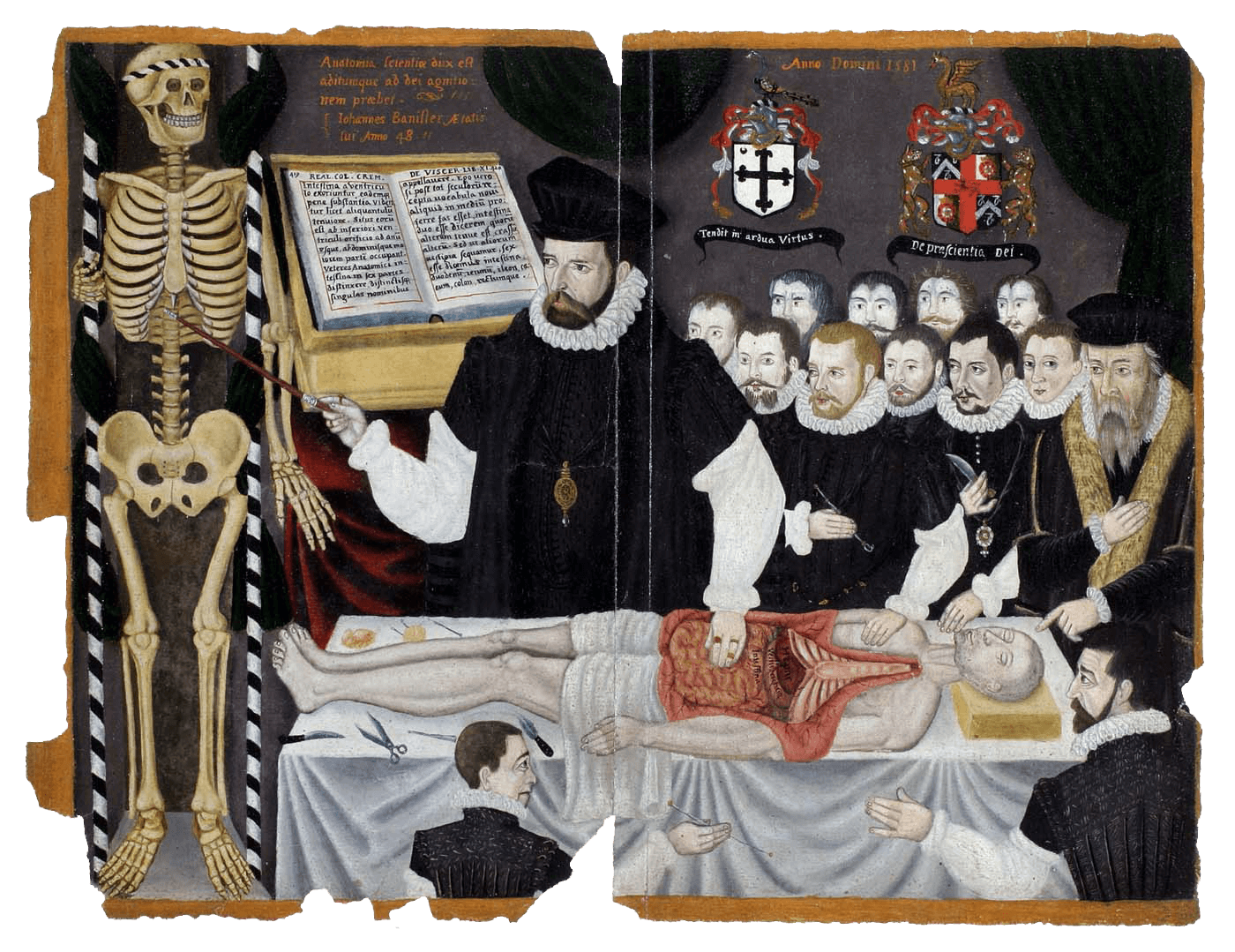

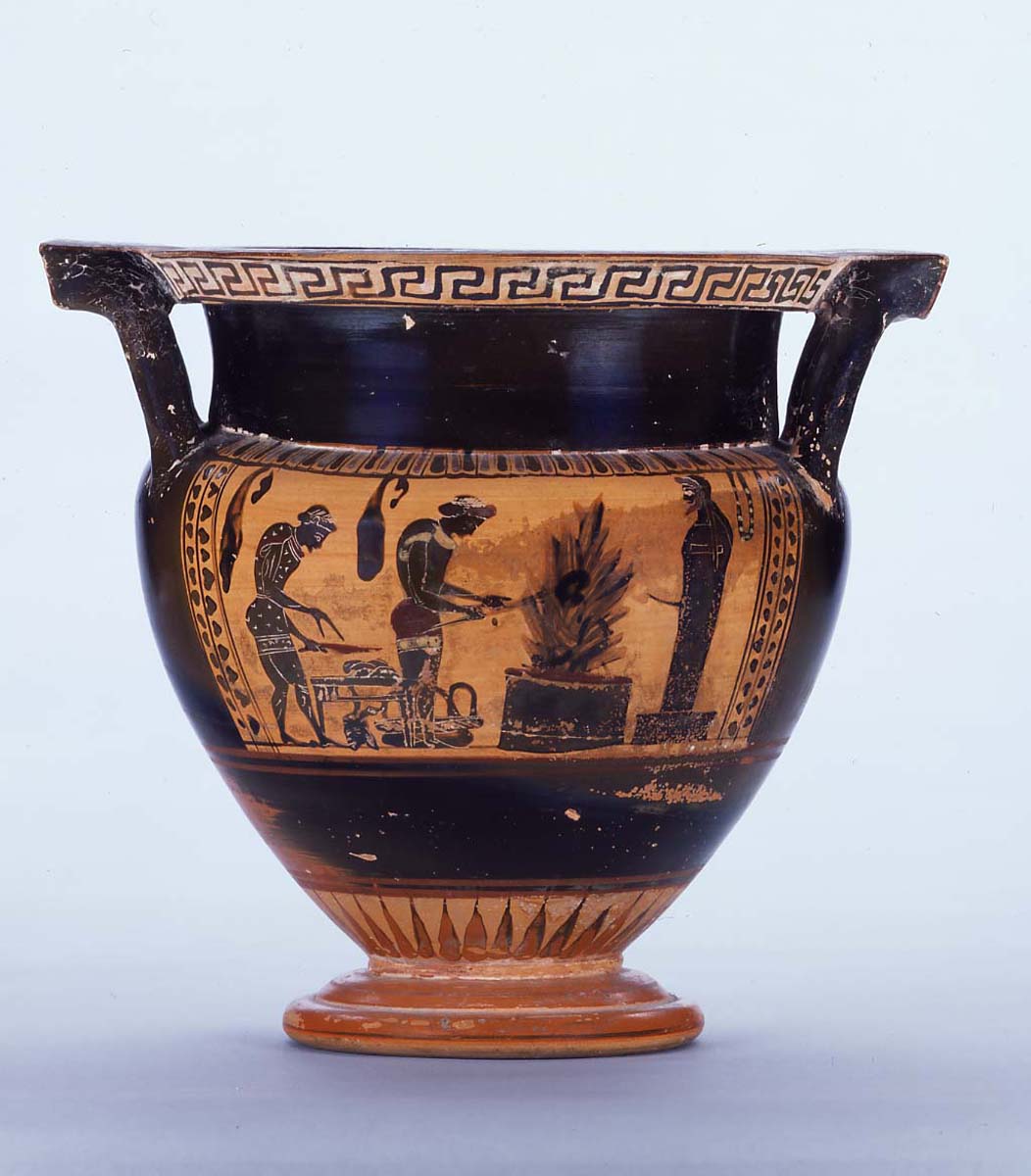

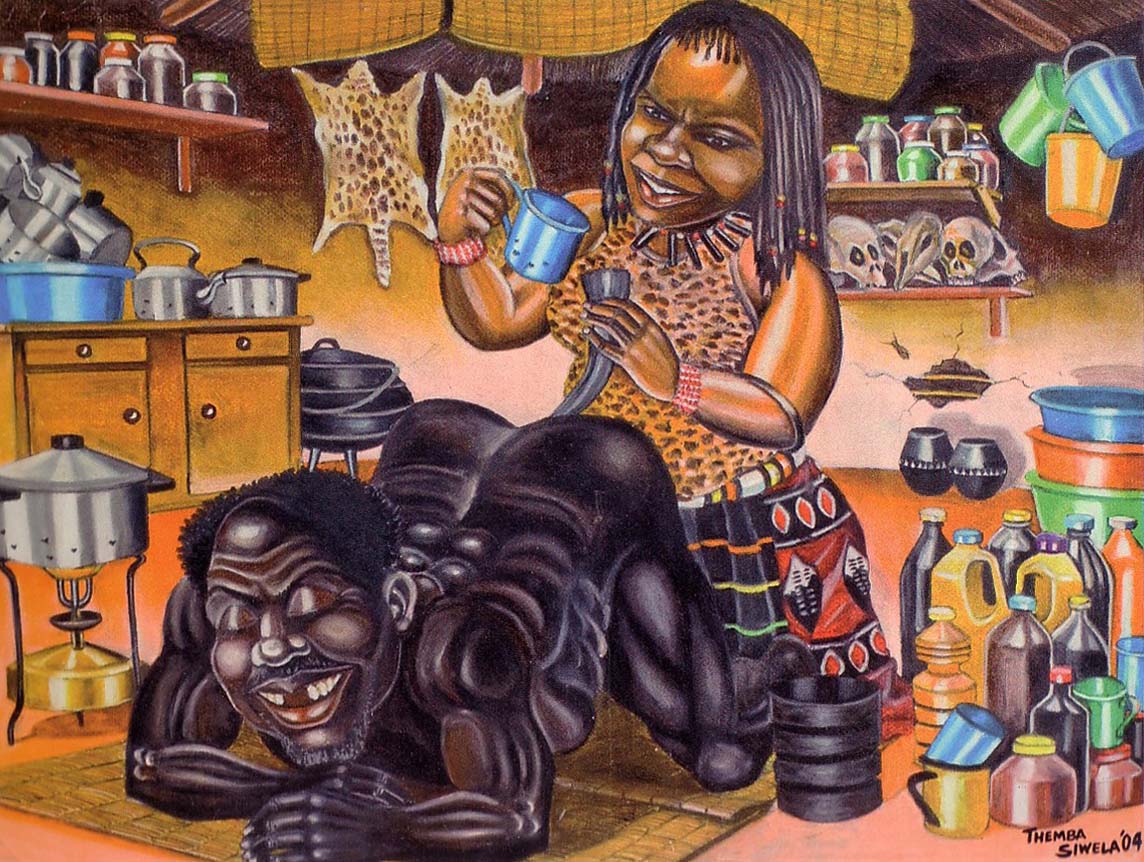

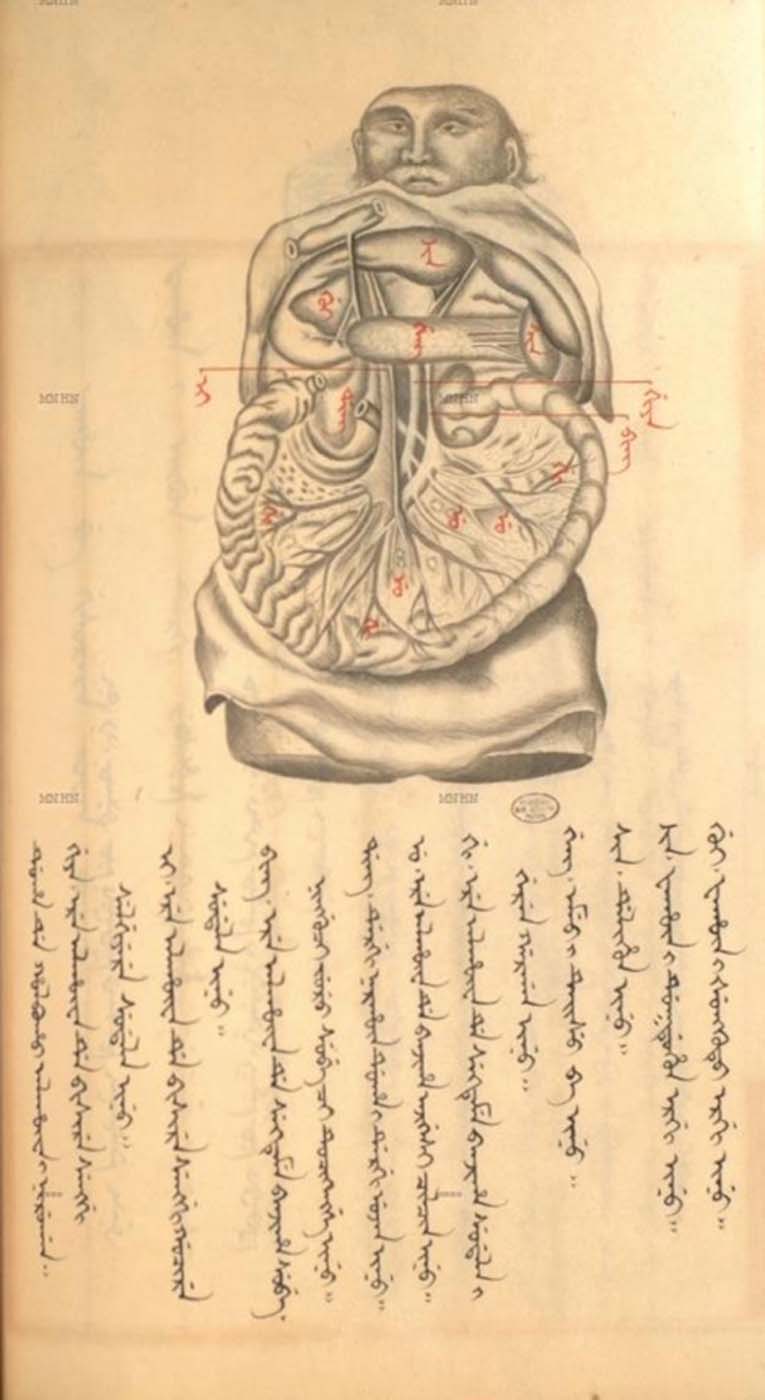

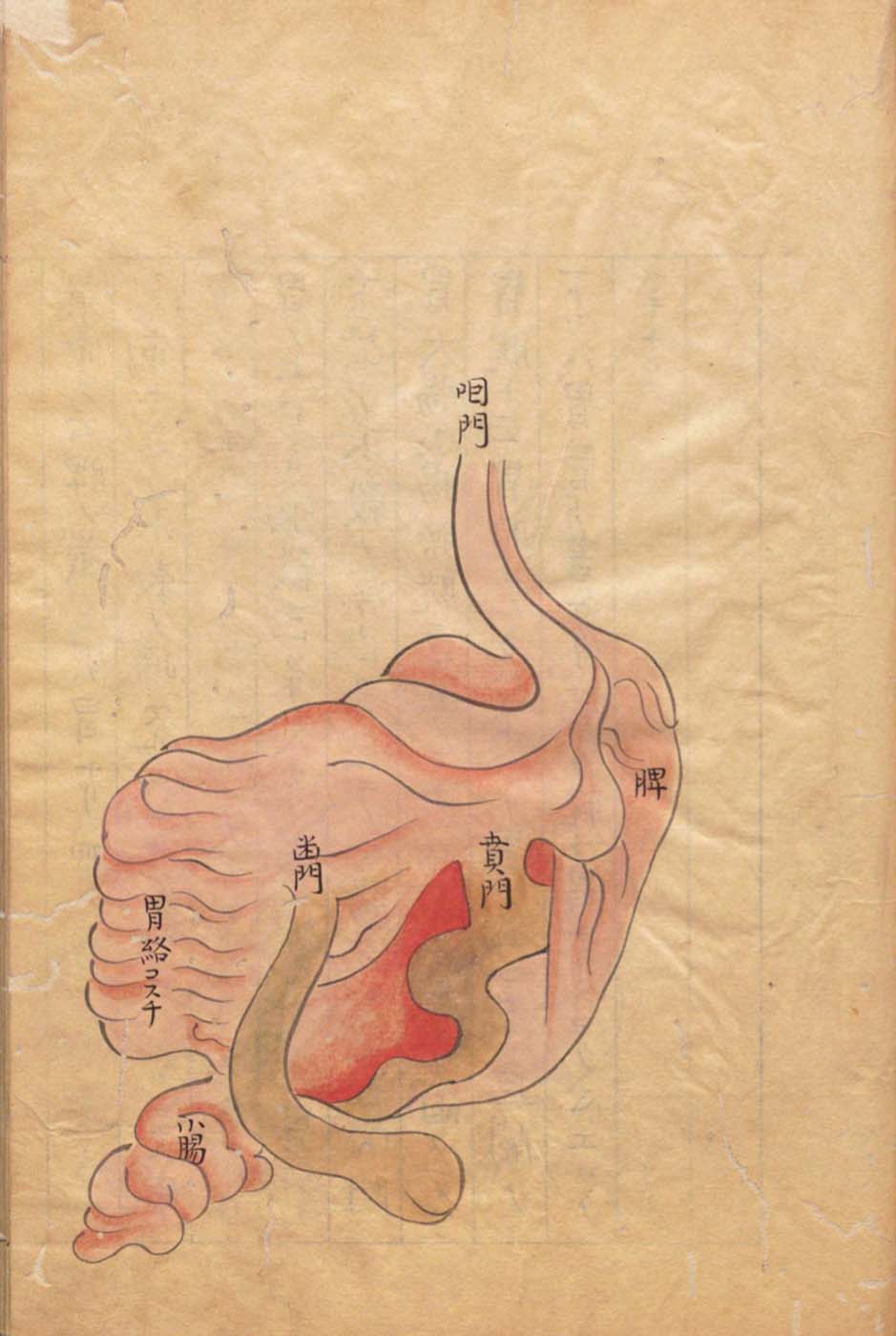

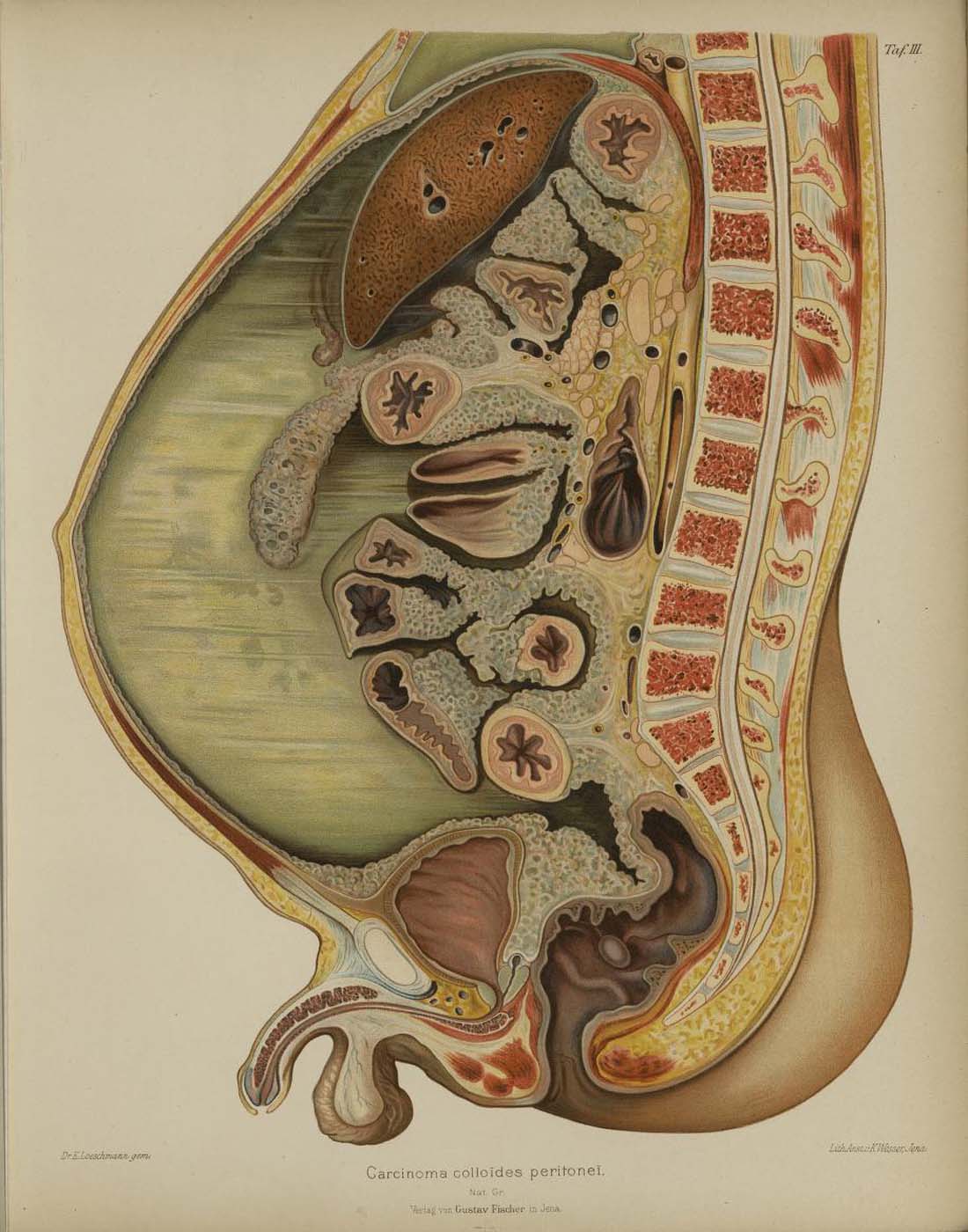

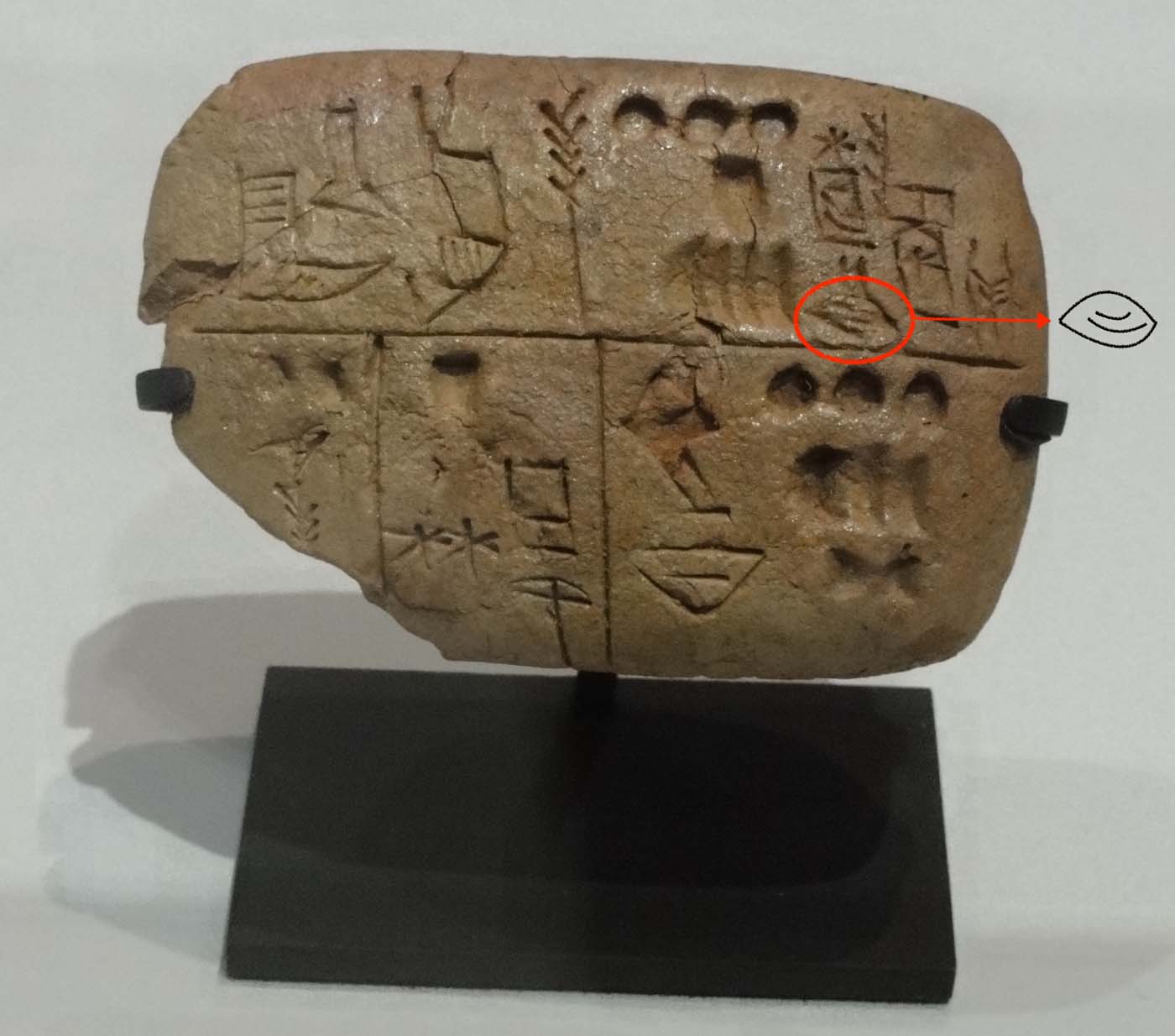

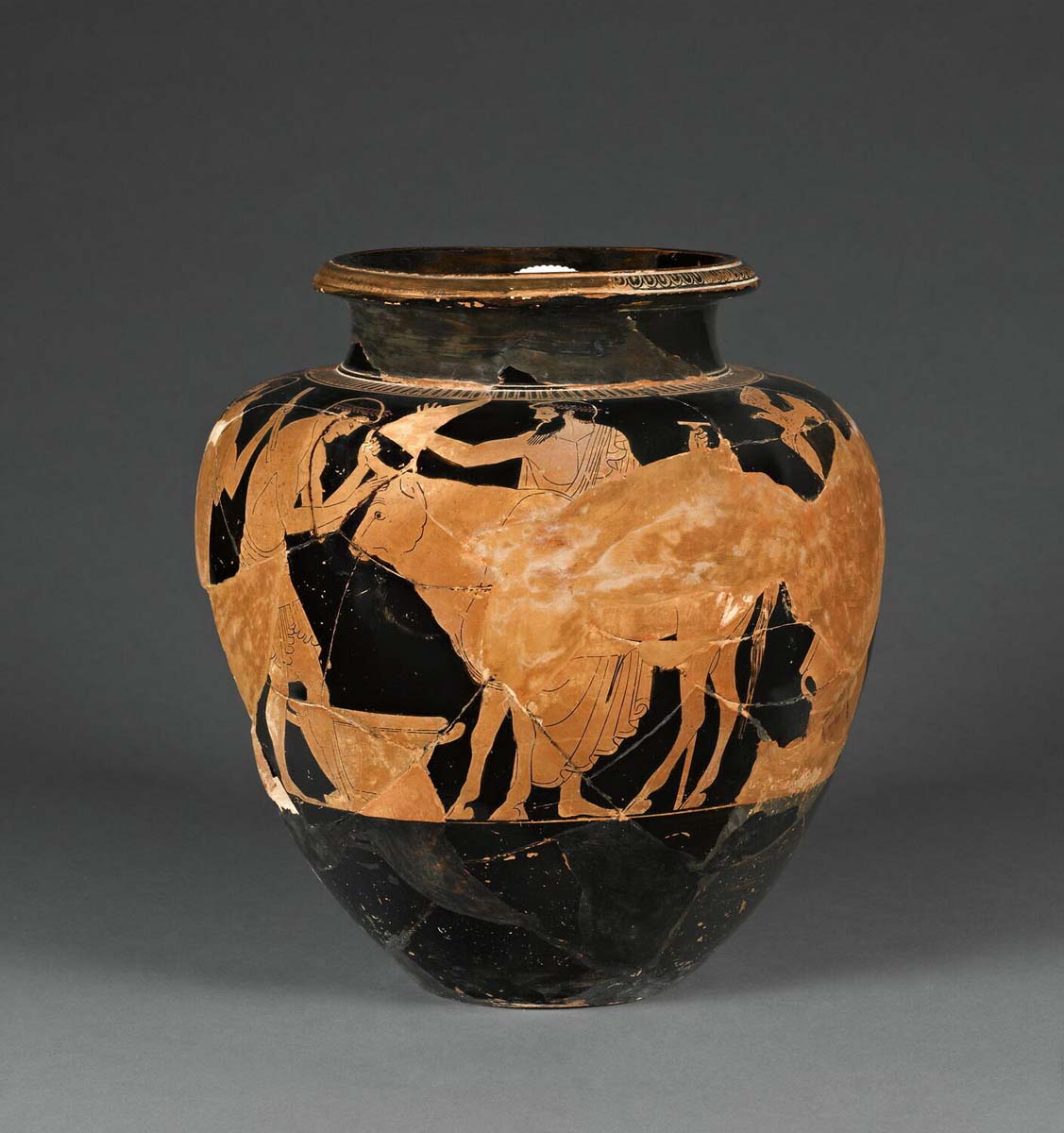

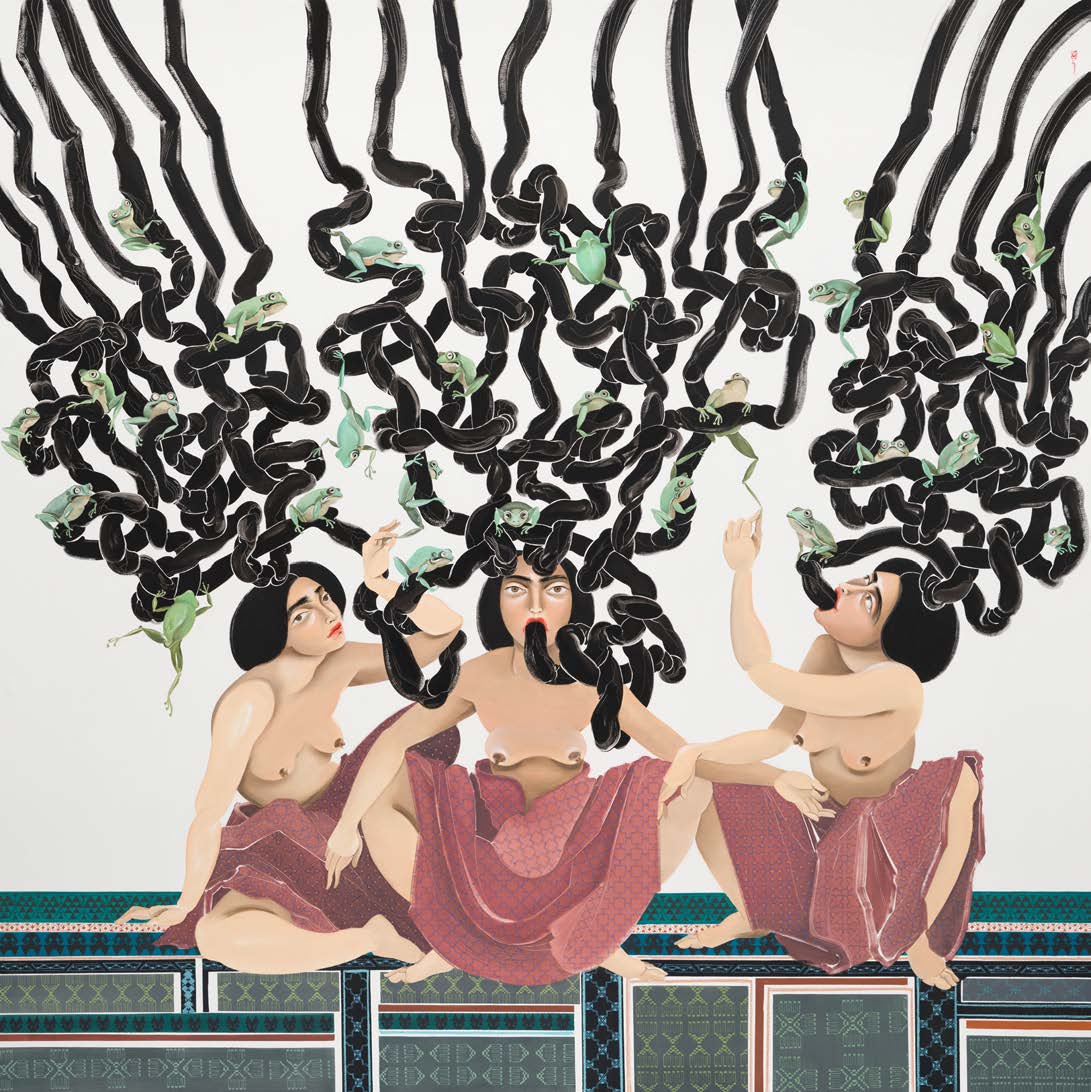

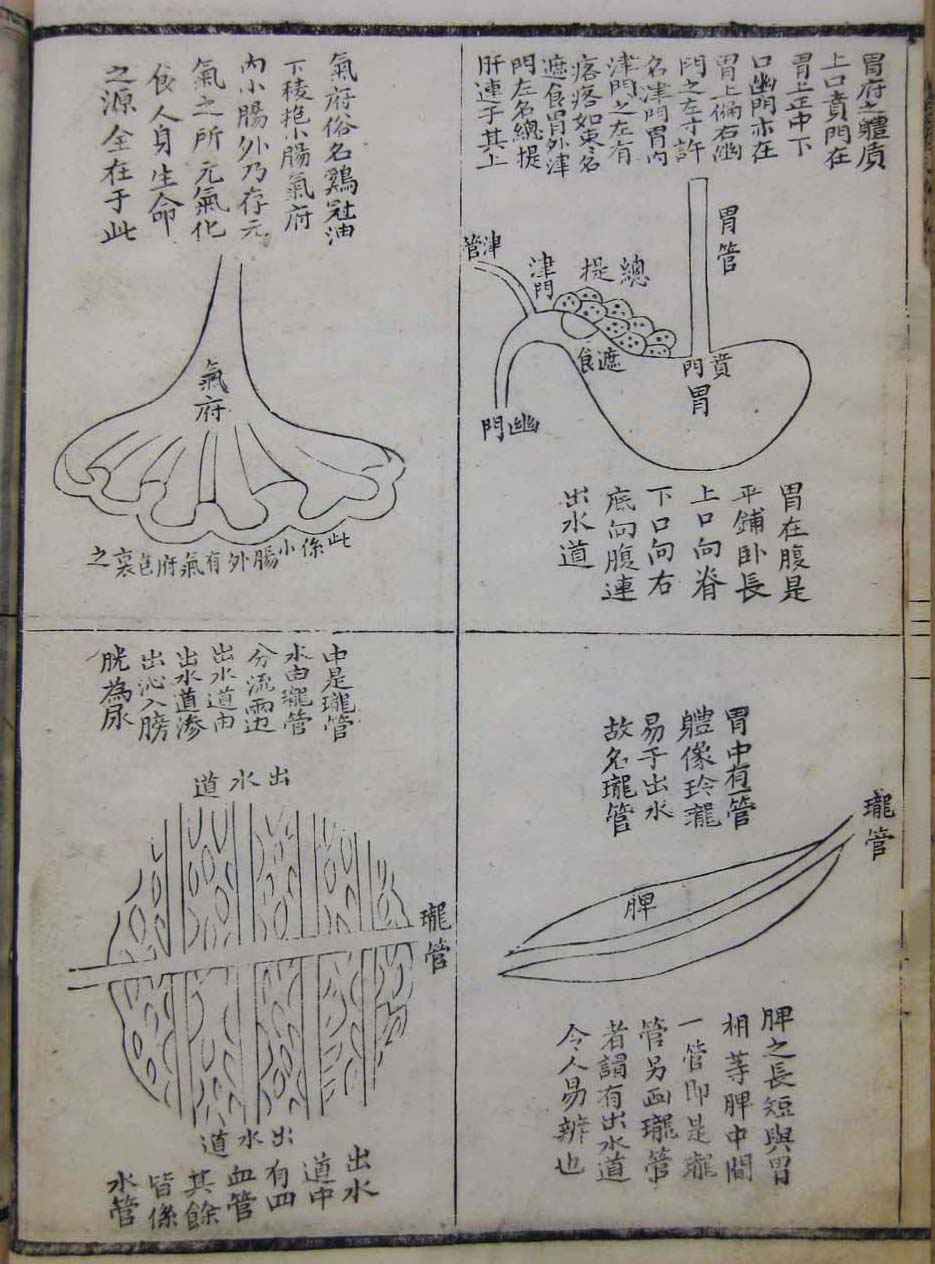

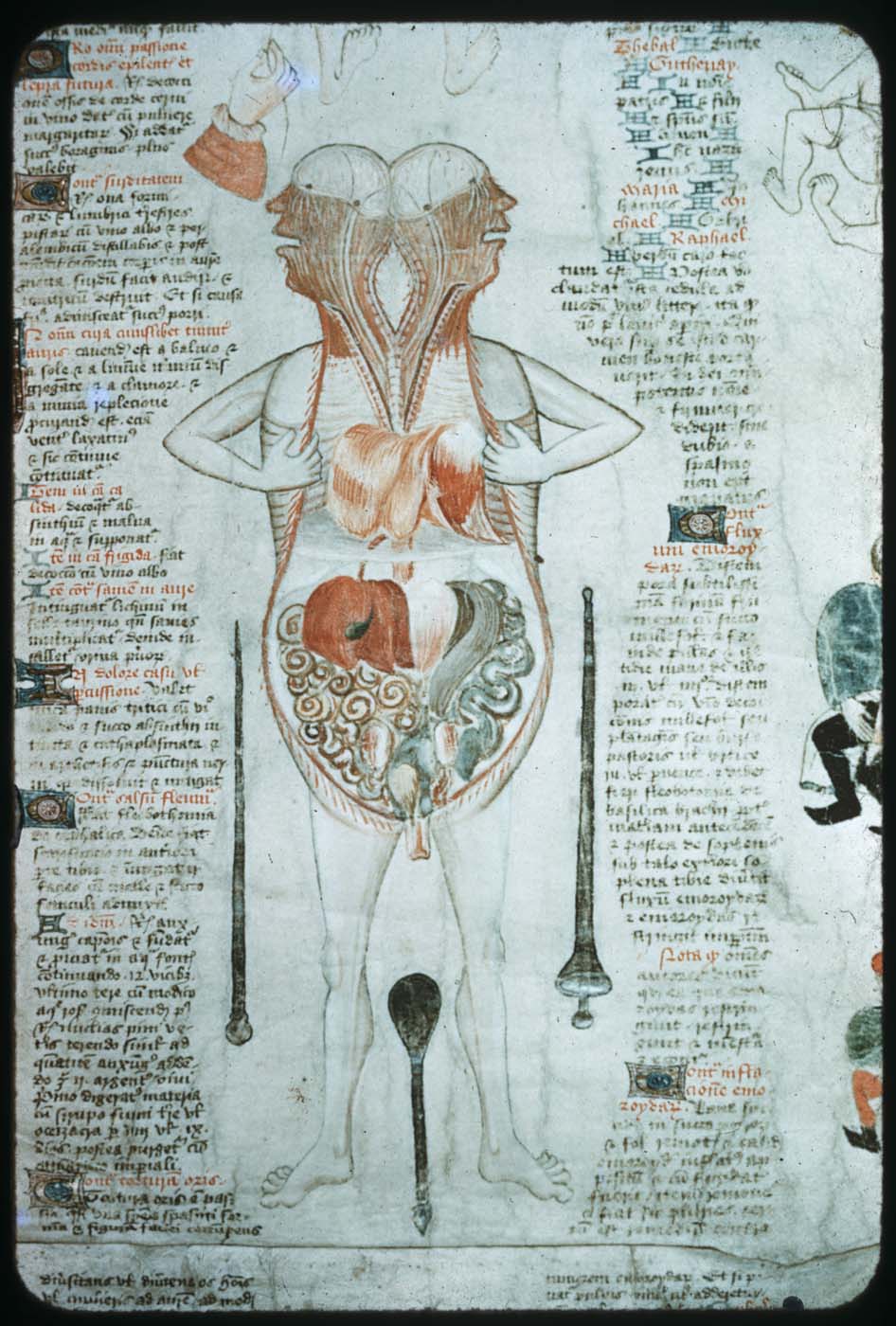

This is a comparative exhibition about the human body, and in particular about one body part, the ‘guts’. For these purposes, ‘guts’ refers to everything found inside the lower torso, the organs and parts traditionally linked to nutrition and digestion, but also endowed with emotional, ethical, and metaphysical significance, depending on the representation and narrative.

By offering access to culturally, socially, historically, and sensorially different experiential contexts, Comparative Guts allows the visitor a glimpse into the variety and richness of embodied self-definition, human imagination about our (as well as animal) bodies’ physiology and functioning, our embodied exchange with the external world, and the religious significance of the way we are ‘made’ as living creatures. This dive into difference is simultaneously an enlightening illustration of what is common and shared among living beings.

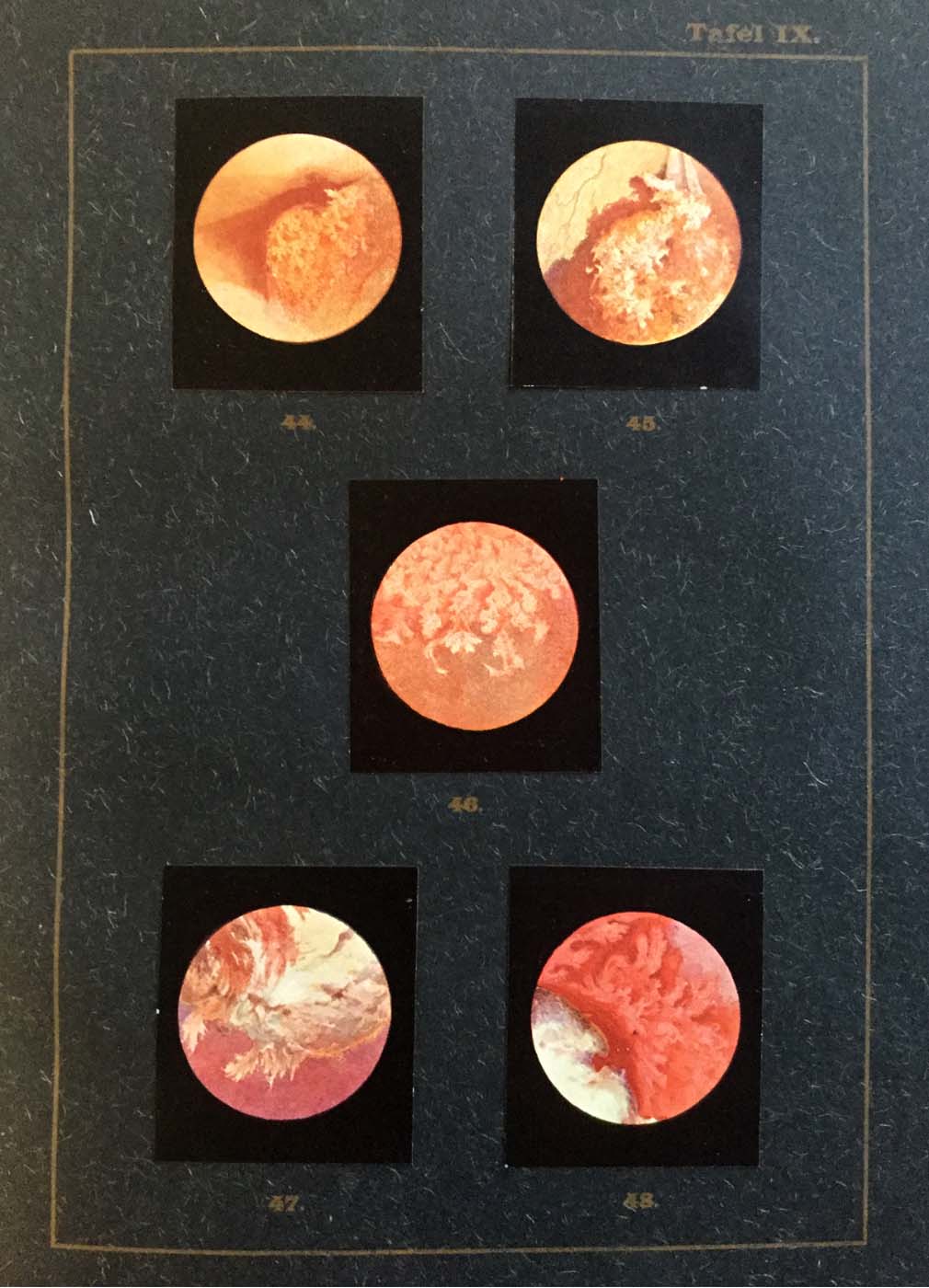

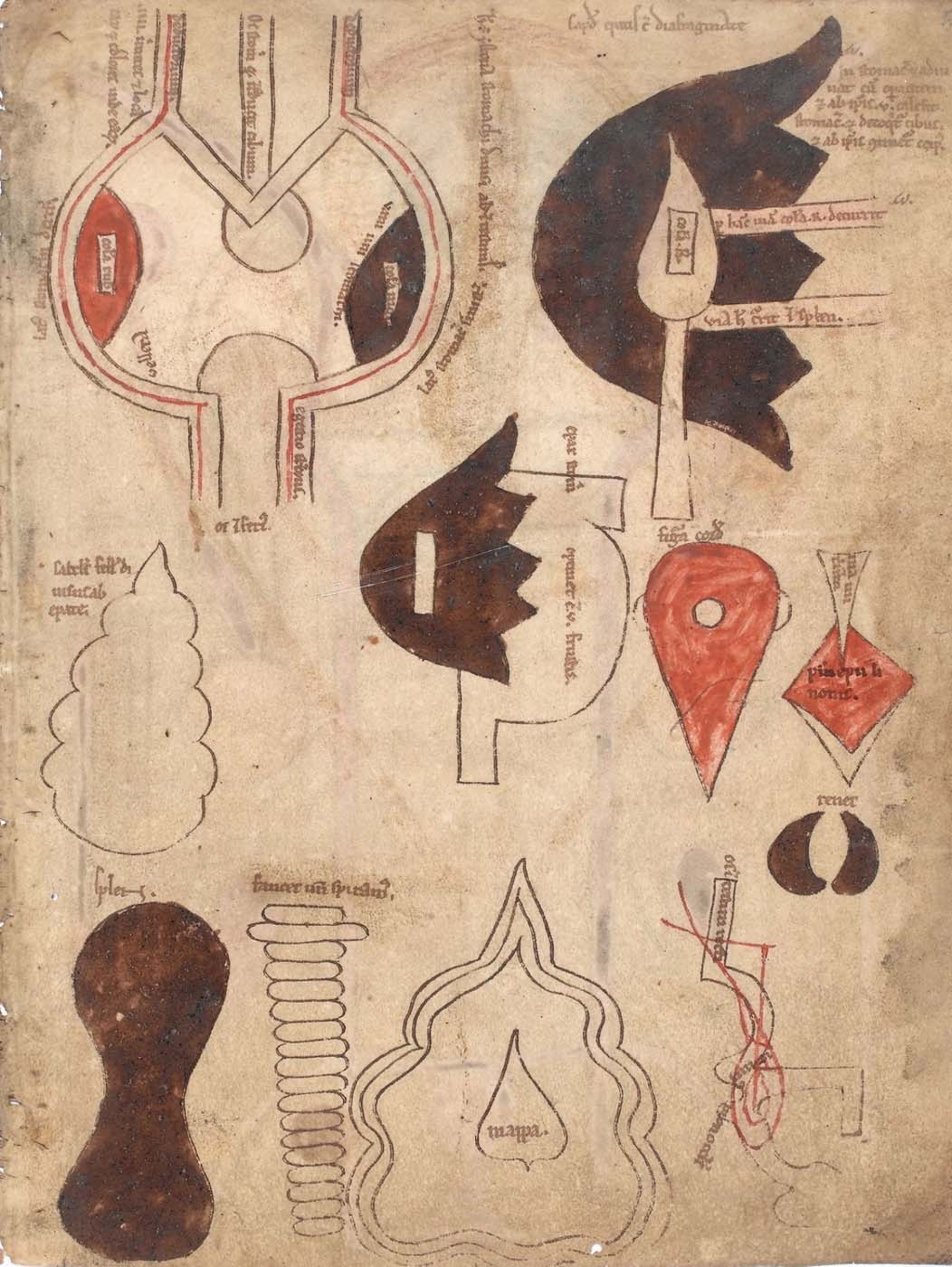

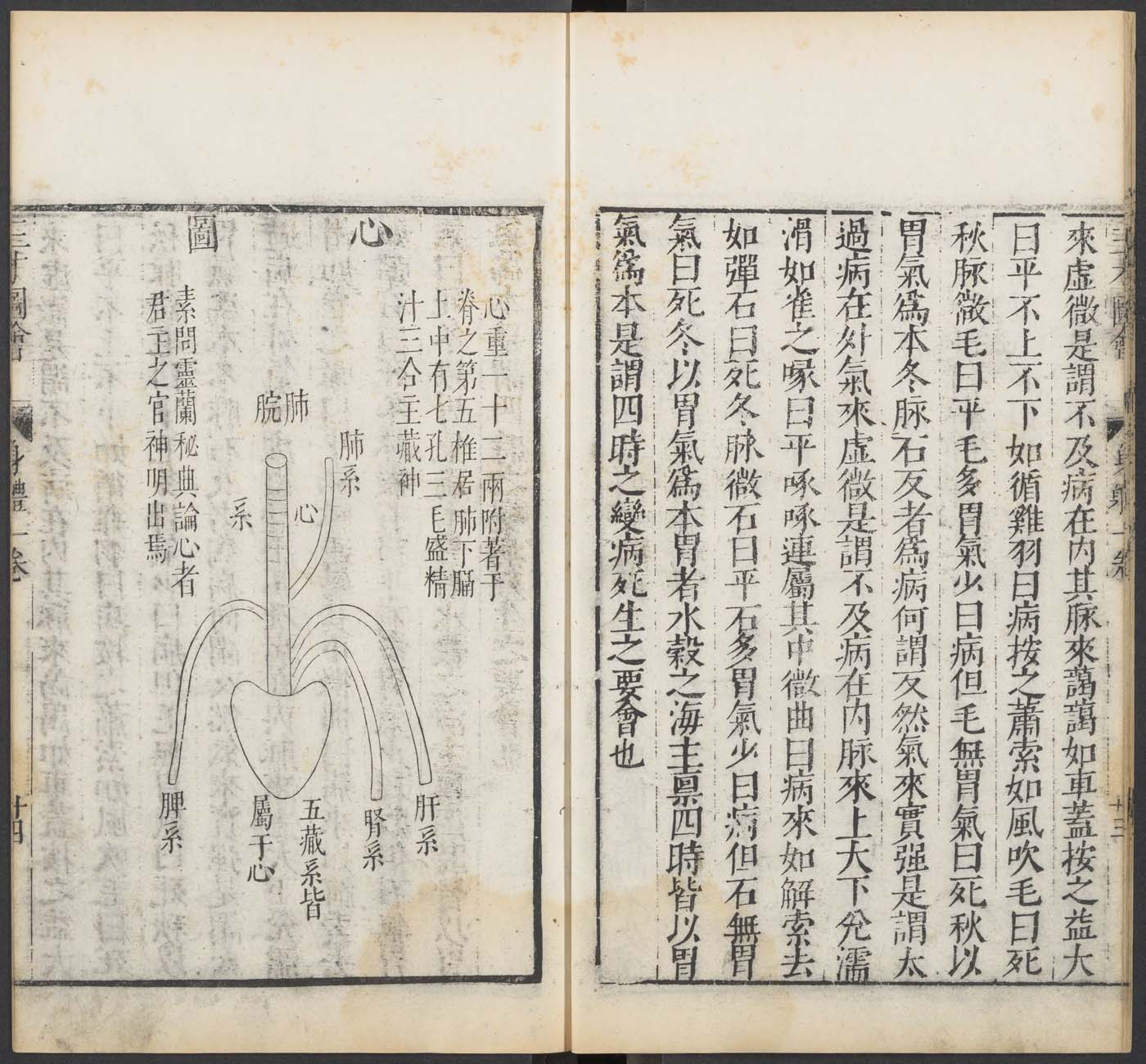

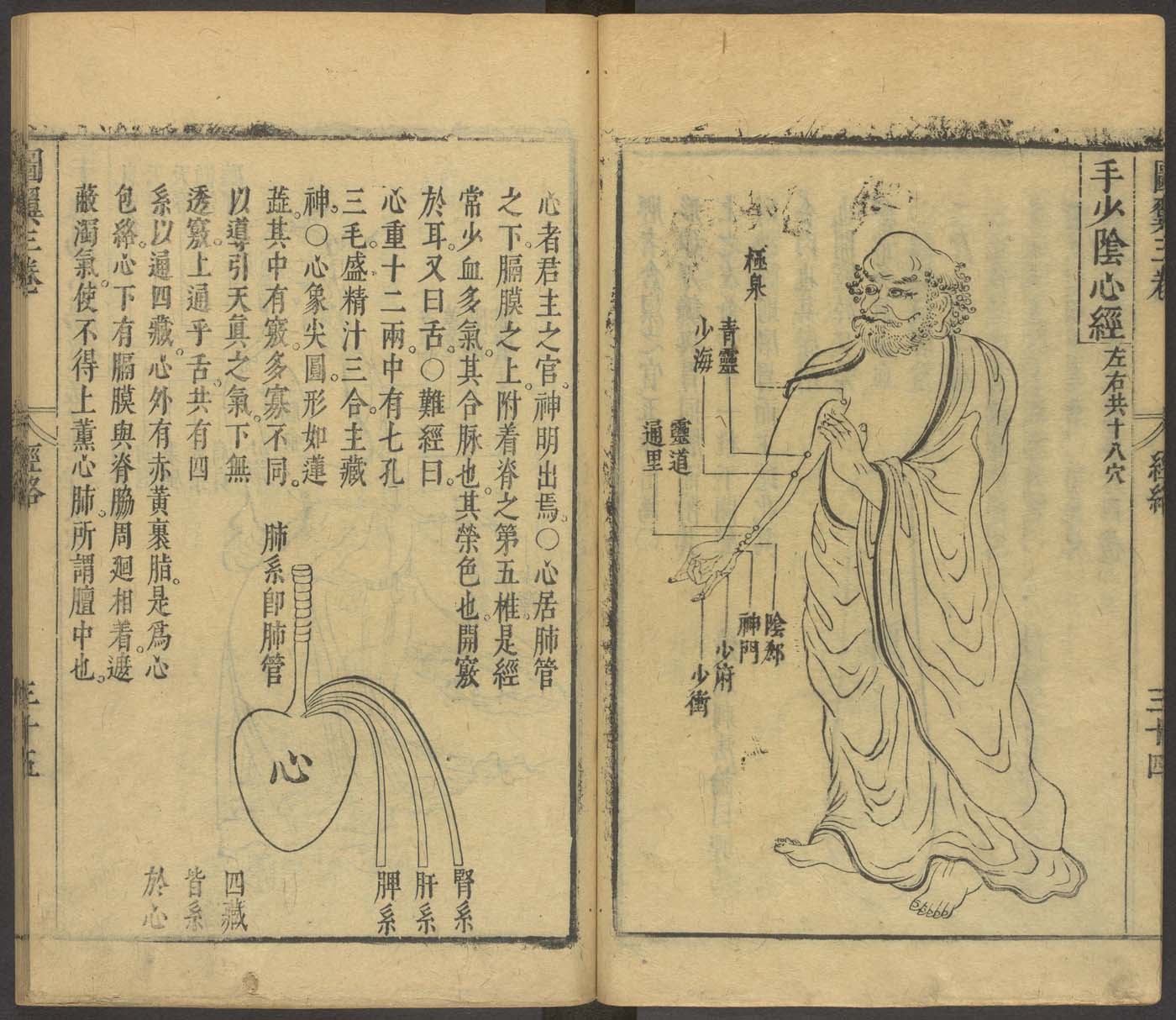

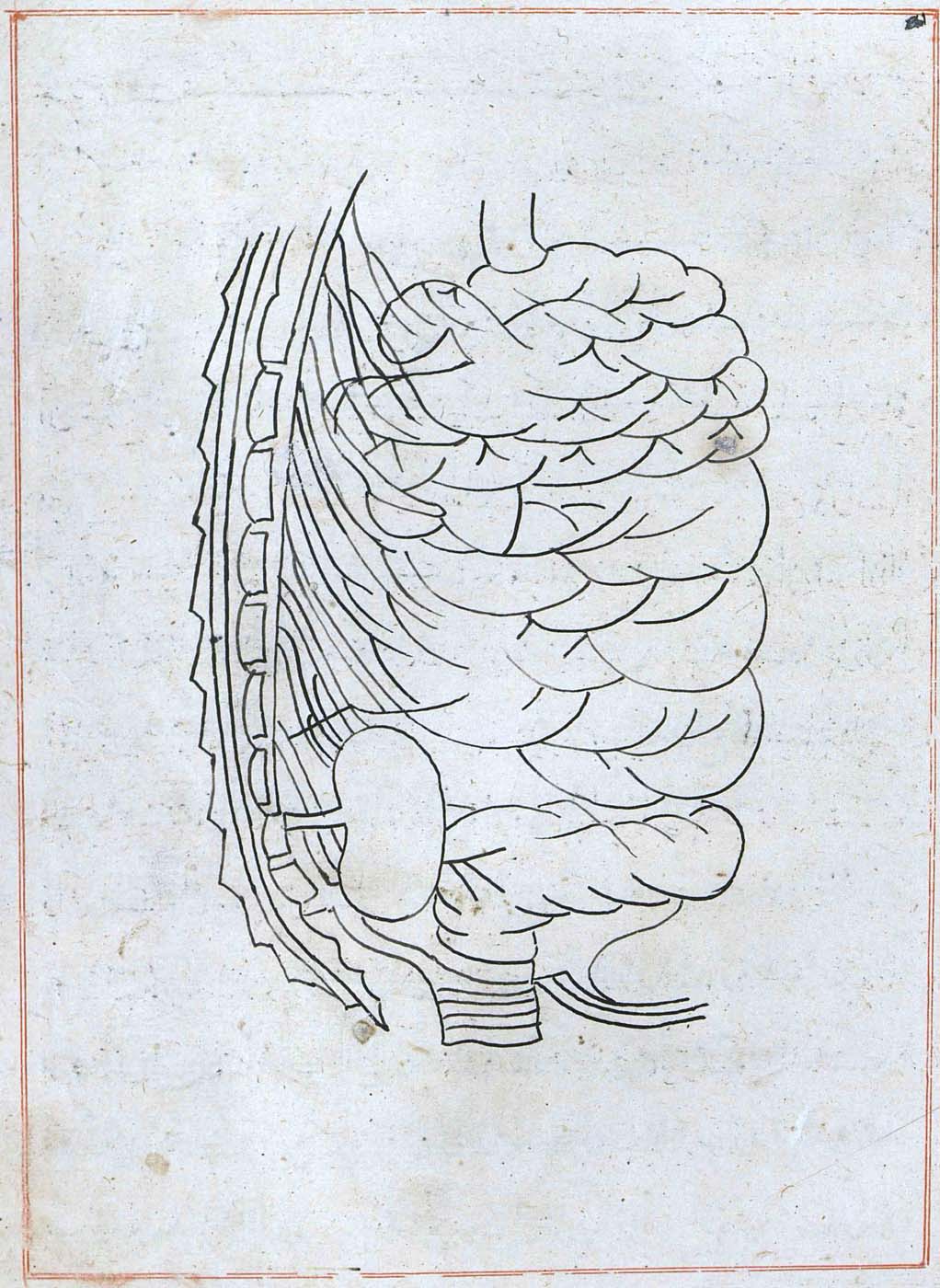

The ‘guts’ are treated here in as neutral and universal a fashion as possible: not necessarily as functional parts of an organism or as a medical item, but as realities experienced in various ways. The most basic distinction is the sensed, volumetric one: solids for the fleshy organs (such as those referred to in English as the liver and the stomach), coils for the intestines and other parts endowed with complexity, folds, and fluidity, and wholes for the guts understood as part of a coherent whole, be it continuous or assembled.

- All

- Whole

- Solid

- Coil